More than three years after The King Arthur Conspiracy was published, the British media have been all over this story (representative sample from The Guardian).

Apparently, a research team from the University of Reading have concluded that the monks of Glastonbury made up the story that King Arthur was buried there, and an awful lot more besides.

I said as much in The King Arthur Conspiracy (and, incidentally, in The Grail, published earlier this year). So - vindicated!

Wonder what else the media will suddenly discover in the coming months, that I also wrote about a few years back ...

(Watch this space)

The Future of History

Showing posts with label King Arthur Conspiracy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label King Arthur Conspiracy. Show all posts

Tuesday, 24 November 2015

Sunday, 4 January 2015

2015

Hello, Happy New Year, and welcome!

It had occurred to me to write up a review of 2014 and the various things that happened last year - from publishing my first university paper on The Faces of Shakespeare to the publication, in September, of Naming the Goddess, in which I have an essay (tweet received this morning from Michigan: 'Loved your essay in "Naming the Goddess"! Great perspective.:)', plus appearances at Stratford Literary Festival and the Tree House Bookshop, lecturing at Worcester University and being a tour guide in Stratford-upon-Avon, completing The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion and writing Shakespeare's Son ('The Life of Sir William Davenant'), and so on. But I didn't get round to it.

Instead, I'm going to preen myself a little over this, which my wife found online a day or two ago. Seems there's to be a rather interesting-looking course on the 'Renaissance of the Sacred Feminine', to be held at Avebury in Wiltshire (good location!) this coming August. Details can be found here.

If you click on the link and scroll down to the bottom section - 'Avebury/Wiltshire Reading List' - you'll see that the last entry concerns my King Arthur Conspiracy book. Alternatively, I'll save you the bother by copying what they wrote:

The King Arthur Conspiracy: How a Scottish prince became a mythical hero

By Simon Andrew Stirling

2012

First discovered during the Scotland adventure, this book is an indispensable read for anyone interested in the Arthur/Merlin/Avalon motif. All the latest research. It will expand your view beyond the emphasis on Glastonbury and Tintagel.

Now, seeing that made me feel really chuffed. It also made me want to get in touch with the organisers and tell them that, actually, all the latest research is probably best found in The Grail, due out in March, but that it was very kind of them to say those things about The King Arthur Conspiracy (and might help with a few book sales), and if there was anything I could do to contribute to their intriguing course in August they had only to ask.

Didn't get round to doing that, either. Although there's still time.

For the meantime, we're holding our breaths and crossing our fingers over the Beoley skull. With any luck, there'll be some scientific investigation of that particular item before too long. Maybe even a TV documentary. I'll keep you posted.

And my Davenant book is coming on apace. New discoveries about Shakespeare's relationship with Jane Davenant. All good clean fun. The manuscript's due to hit the editor's desk at the start of June.

There's another project in the wings, which I'll mention more about if things keep going smoothly. All in all, 2015 has a very exciting feel about it. I hope yours does, too.

TTFN!

It had occurred to me to write up a review of 2014 and the various things that happened last year - from publishing my first university paper on The Faces of Shakespeare to the publication, in September, of Naming the Goddess, in which I have an essay (tweet received this morning from Michigan: 'Loved your essay in "Naming the Goddess"! Great perspective.:)', plus appearances at Stratford Literary Festival and the Tree House Bookshop, lecturing at Worcester University and being a tour guide in Stratford-upon-Avon, completing The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion and writing Shakespeare's Son ('The Life of Sir William Davenant'), and so on. But I didn't get round to it.

Instead, I'm going to preen myself a little over this, which my wife found online a day or two ago. Seems there's to be a rather interesting-looking course on the 'Renaissance of the Sacred Feminine', to be held at Avebury in Wiltshire (good location!) this coming August. Details can be found here.

If you click on the link and scroll down to the bottom section - 'Avebury/Wiltshire Reading List' - you'll see that the last entry concerns my King Arthur Conspiracy book. Alternatively, I'll save you the bother by copying what they wrote:

The King Arthur Conspiracy: How a Scottish prince became a mythical hero

By Simon Andrew Stirling

2012

First discovered during the Scotland adventure, this book is an indispensable read for anyone interested in the Arthur/Merlin/Avalon motif. All the latest research. It will expand your view beyond the emphasis on Glastonbury and Tintagel.

Now, seeing that made me feel really chuffed. It also made me want to get in touch with the organisers and tell them that, actually, all the latest research is probably best found in The Grail, due out in March, but that it was very kind of them to say those things about The King Arthur Conspiracy (and might help with a few book sales), and if there was anything I could do to contribute to their intriguing course in August they had only to ask.

Didn't get round to doing that, either. Although there's still time.

For the meantime, we're holding our breaths and crossing our fingers over the Beoley skull. With any luck, there'll be some scientific investigation of that particular item before too long. Maybe even a TV documentary. I'll keep you posted.

And my Davenant book is coming on apace. New discoveries about Shakespeare's relationship with Jane Davenant. All good clean fun. The manuscript's due to hit the editor's desk at the start of June.

There's another project in the wings, which I'll mention more about if things keep going smoothly. All in all, 2015 has a very exciting feel about it. I hope yours does, too.

TTFN!

Sunday, 2 November 2014

Pagan Pages

Just been told that an interview with me is now up on the PaganPages.org website.

So, with thanks to Mabh Savage, I give you ... The Pagan Pages Interview with Author Simon Stirling. I think it's a good one.

Toodle-pip!

So, with thanks to Mabh Savage, I give you ... The Pagan Pages Interview with Author Simon Stirling. I think it's a good one.

Toodle-pip!

Labels:

Arthur,

Artuir mac Aedain,

Beltane,

Grail,

Gunpowder Plot,

Halloween,

King Arthur Conspiracy,

Moon Books,

Muirgein,

Myrddin Wyllt,

Scotland,

The History Press,

Who Killed William Shakespeare

Sunday, 17 August 2014

Alyth, the Scene of Arthur's Last Battle

While I work on Shakespeare's Son - my biography of Sir William Davenant, a man of whom I'm becoming increasingly fond - The Grail continues to make its way through the publishing process, courtesy of Moon Books. So, by way of a sneak preview, in this post I shall offer up some of the evidence for the location of Arthur's last battle.

The Battle of Circenn

You probably think Arthur's last battle was fought at a place called "Camlann". I've been unable to find any reference to that place-name before the Middle Ages. The very earliest mentions of anyone called Arthur in the records indicate that he died in a battle fought in Angus, Scotland.

Adomnan of Iona's Life of Columba (circa 697) tells us that Artur son of Aedan was present when his father was "ordained" king of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574. The saint predicted the fates of Aedan's sons, announcing that Artur would "fall in battle, slain by enemies". Adomnan assured his readers that this prophecy came true when Artur and at least one of his brothers was killed in a "battle of the Miathi".

The Miathi, or Maeatae, were a Pictish tribe: essentially, they held the low-lying lands to the south and east of the Highland massif. Another Latinate term for these people was Verturiones.

The Irish annals, which drew at least some of their information from the records kept by Columba's monks on the Isle of Iona, specify that Artur son of Aedan died in a "battle of Circenn". This refers to the Pictish province which was roughly contiguous with today's Angus and the Mearns. The term Circenn combined the Gaelic cir, meaning a "comb" or "crest", and cenn, "heads". Circenn, then, was the land of the Comb-heads. This tells us that the Miathi Picts modelled their appearance on their totem beast, the boar (rather like their compatriots in the Orkneys, the Orcoi, from orc - a young boar). Indeed, it is possible that the Latinate name for the Verturiones tribe combines verres and turio and indicates the "offshoots" or "offspring" of the "boar", while the very term "Pict" (variant, "Pecti", "Pecht") quite possibly derived from the Latin pecten, a "comb".

Now, let's look at "Camlann" - the traditional name for Arthur's last battle. Its first appearance in the records comes in an entry interpolated into the Welsh Annals, where it refers to a gueith cam lann or "strife of cam lann". By the time this came to be written down, the region in which Artur son of Aedan died was speaking a version of Northumbrian Old English which became the dialect known as Lowland Scots. In that dialect, cam lann would mean "comb land".

In other words, "Camlann" is merely an anglicised version of the Gaelic Circenn, the land of the "Comb-heads" in which the first Arthur on record fell in a cataclysmic battle.

Culhwch and Olwen

One of the oldest of the Welsh (i.e. British) tales to feature Arthur is that of Culhwch ac Olwen. It forms a sort of mythologised, potted account of Arthur's career, culminating in the desperate and bloody hunt for a king who - for his sins - was turned into a boar. This hunt begins with a violent amphibious landing, at a site which can be identified as Cruden Bay, on the Aberdeenshire coast, after which Arthur is met by the "saints of Ireland" who "besought his protection". The dreadful Boar-King is challenged and chased from Esgeir Oerfel, the "Cold Ridge" of the Grampians, the Boar-King making his way across country towards Llwch Tawy (Loch Tay) before he is intercepted by Arthur and his men and driven into a river.

In The King Arthur Conspiracy I identified the treacherous Boar-King as Morgan the Wealthy, a renegade British prince who abducted Arthur's wife, Gwenhwyfar, and escaped into the land of the Miathi Picts (his bolt hole appears to have been the fortified Hill of Tillymorgan in Strathbogie). The site where Morgan finally came to grief is marked by the "Morganstone" on the west bank of the River Ericht, a short distance to the west of the Hill of Alyth in the great vale of Strathmore in Angus.

Arthurian Connections with Alyth

Before we proceed, let us consider some ancient references to Arthur and his family in the context of Alyth and its immediate vicinity.

In addition to having a son named Artur or Artuir, King Aedan of the Scots had a daughter called Muirgein. According to Whitley Stokes, editing and translating the Martyrology of a 9th-century Irish monk called Oengus, Muirgein daughter of Aedan was born "in Bealach Gabrain".

The inability of certain scholars to find a "Bealach Gabrain" in Scotland has led some to argue that Muirgein daughter of Aedan was utterly unconnected with Artur son of Aedan. But place-names evolve. The Gaelic term bealach, meaning a "pass" or "gorge", usually appears as "Balloch" on today's maps. There is a "Balloch" which runs along the feet of Barry Hill and the adjacent Hill of Alyth in Strathmore.

Furthermore, this "Balloch" or bealach was in a region named after the grandfather of Artur and Muirgein. Gabran was the father of Aedan. He ruled the Scots for twenty years until his death in about AD 559 and gave his name to the region of Gowrie (a corruption of Gabran). The "Balloch" near Alyth was in Gabran's land (Gabrain) and lies close to the town of Blairgowrie, which also recalls the name of Arthur's grandfather. The "Balloch" at the foot of the Hill of Alyth was almost certainly the "Bealach Gabrain" or "pass of Gowrie" where Arthur's (half-)sister, Muirgein daughter of Aedan mac Gabrain, was born. To pretend that the Balloch of Gowrie could not have been "Bealach Gabrain" because they are not spelled the same way these days is tantamount to claiming that Londinium and London could not have been the same place.

So Arthur's sister, Muirgein (latterly, Morgan le Fay), was born near Alyth. Writing in about 1527, the Scottish historian Hector Boece also indicated that Arthur's wife was buried at Meigle, which is just a mile or two south of Alyth. Hector Boece's local tradition recalled Gwenhwyfar as Vanora (via Guanora) and claimed that she had been held hostage in the Iron Age hill-fort atop Barry Hill, adjacent to the Hill of Alyth, before she was executed and buried in what is now the kirkyard at Meigle. A carved Pictish standing stone, now on display at the Meigle museum, reputedly depicts the execution or burial of Arthur's wife.

Y Gododdin

One of the best sources of information about Arthur's last battle is the ancient epic, Y Gododdin. This was composed and sung by Aneirin, a British bard of the Old North, and can be dated to circa AD 600 (the date of Arthur's last battle is given in the Irish annals as, variously, AD 594 and 596).

Unfortunately, the relevance of Aneirin's elegiac tribute to the warriors of Lothian (the "Gododdin") has been missed by scholars who want to believe that the poem bemoans the destruction of a British war-band from the Edinburgh area which had the misfortune to be wiped out at a mythical battle fought at Catterick in North Yorkshire. No evidence exists that any such battle was fought. The Angles (forerunners of the English) preferred not to recollect their defeats but were happy to remember, and to boast about, their victories. If the Angles of Northumbria had indeed obliterated a British band of heroes from Lothian at Catterick, we might assume that they would have remembered doing so. And no scholar has yet explained the presence of "Irishman and Picts" at this imaginary battle in Anglian territory.

A verse or two of Y G[ododdin, added at a later date than the original composition, described a battle fought in Scotland (Strathcarron) in AD 642 and the death in that battle of a Scottish king who just happened to be a nephew of Artur son of Aedan. This interpolation does at least suggest that the subject of the original poem was a battle fought in roughly the same area (Scotland) by the family of Artur and his father Aedan. The Y Gododdin poem also mentions various famous warriors who appear in the early accounts of Arthur's career and who were contemporary with Artur son of Aedan.

One surviving version of Y Gododdin even mentions Artur/Artuir by name:

Gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef Arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

Confused by the misidentification of the battle sung about by Aneirin in Y Gododdin, and the assumption that Arthur himself could not have been present at that battle, scholars have persistently mistranslated this verse - mostly in an attempt to render the second half of the second line, "He was no Arthur". But Aneirin's verse should properly be translated thus:

Black ravens [warriors] sang in praise of the hero [Welsh, arwr]

of Circenn [transliterated into Welsh as "caer ceni"]. He blamed Arthur;

the dogs cursed in return for our wailing/lamentation ...

Aneirin indicated, in his Y Gododdin elegy, precisely where the final battle took place:

Eil with gwelydeint amallet

y gat veirch ae seirch greulet

bit en anysgoget bit get ...

Which translates as:

Again they came into view around the alled,

the battle-horses and the bloody armour,

still steadfast, still united ...

The "alled" was Aneirin's Welsh-language attempt at the Gaelic Allaid - also Ailt - or the Hill of Alyth.

Breuddwyd Rhonabwy

The extraordinary medieval Welsh tale of The Dream of Rhonabwy actually provides a description of the scene in the hours before Arthur's last battle was fought. The visionary seer, Rhonabwy, finds himself crossing a great plain with a river running through it (Strathmore). He is met by a character call Iddog, "Churn of Britain", who admits that it was he who caused the cataclysmic "battle of Camlan" by betraying Arthur. In company with Iddog, Rhonabwy approaches the "Ford of the Cross" (Rhyd-y-Groes) on the river. A great army is encamped on either side of the road and Arthur is seated on a little flat islet in the river, beside the ford.

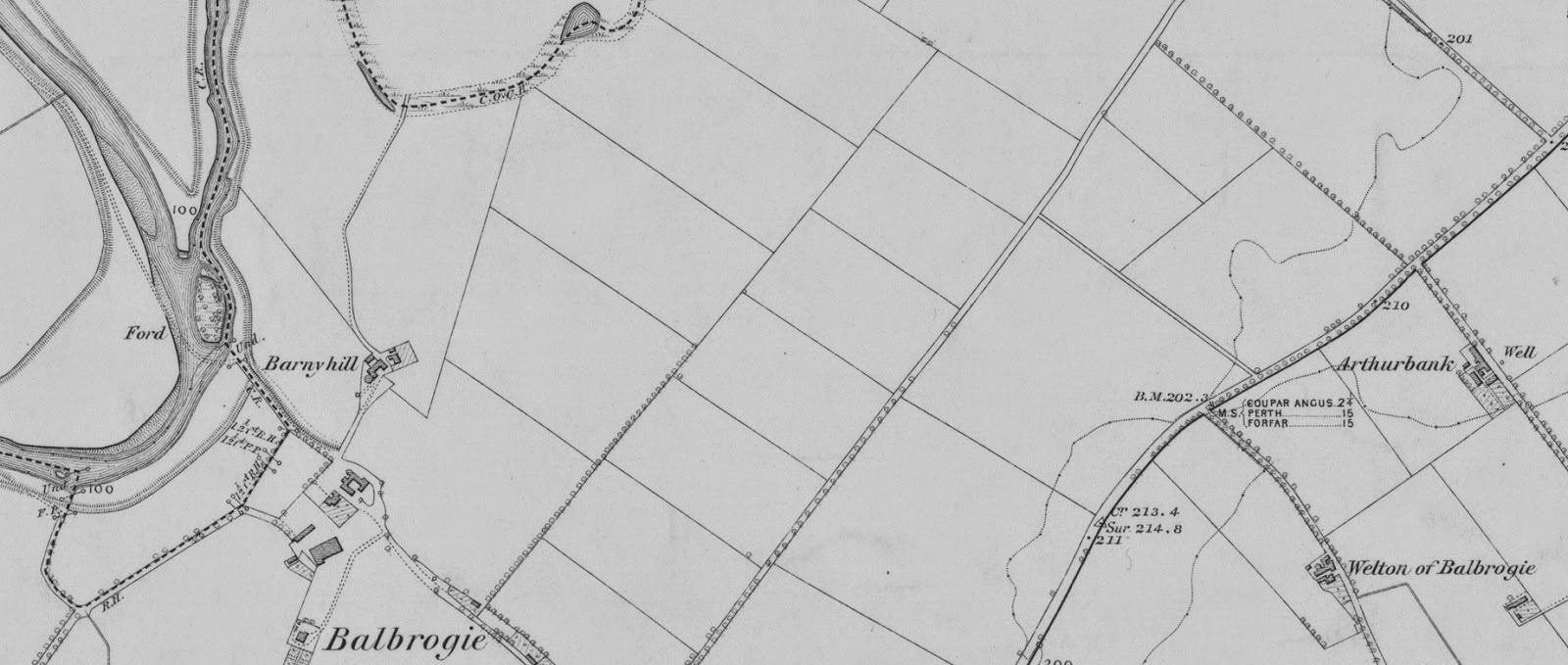

The topography precisely matches the detail from a 19th-century Ordnance Survey map of the area around Alyth seen at the top of this post. On the right-hand side of the detail is the ridge known as Arthurbank, which lies along the River Isla, opposite the junction of the River Ericht with the River Isla (a few miles down the Ericht from the site of the Morganstone). A little flat islet lies in the River Isla, close to the Arthurbank shore, and a ford runs alongside this little islet, exactly as described in the Welsh account of Rhonabwy's dream.

Aneirin also mentioned this ford in his Y Gododdin poem as rhyd benclwyd - the "ford" of the "grey" or "holy mount". There is, indeed, a Greymount marked on the map, a short distance to the north of the ford on the Isla. In his Agriculture of Perthshire, published in 1799, the Rev. Dr Robertson described the discovery of a "large Druidical temple" at Coupar Grange, adjacent to this ford. A standing stone found in this "temple" would no doubt have been rebranded a "cross" by the early Christians, so that the ford across the Isla, beside the little flat islet, would have become known as the Ford of the Cross (Rhyd-y-Groes), as described in The Dream of Rhonabwy, or the "Ford of the Grey/Holy Mount" (rhyd benclwyd) as described by Aneirin.

Until the late 18th century, an Arthurstone stood at the south-eastern edge of the Arthurbank ridge (its presence is still marked on the map). This Arthurstone corresponds to the Morganstone, a few miles away up the River Ericht, and marks the spot where Arthur fell in his battle with the Boar-King of the Miathi Picts in the land of the "crested" Comb-heads, Camlann.

The Head of the Valley of Sorrow

After the battle, Arthur's wife Gwenhwyfar was executed and buried only a mile or so away at Meigle. The legend of Culhwch and Olwen (which, interestingly, features a treacherous individual identified as Grugyn, who also appears in Aneirin's Y Gododdin) tells us that, after the battle at the river with the dangerous Boar-King, Arthur and his heroes once more "set out for the North" to overcome a fearsome witch. She was found inside a cave at Penn Nant Gofid - the "Head of the Valley of Sorrow"- on "the confines of Hell" (which we can interpret as the edge of the territory controlled by those boar-like Miathi Picts). The Welsh gofid ("sorrow/trouble/affiction/grief") appears to have been something of a pun, for another Welsh word for sorrow or grief is alaeth (compare Ailt, Allaid and Alyth, the "Head of the Valley of Alyth" being the very hill on which Arthur's wife is rumoured to have been held prisoner before her execution and burial nearby at Meigle).

In the Welsh tale, this witch is known as Orddu (that is, Gorddu - "Very Black"). A similar legend from the Isle of Mull, whose Arthurian associations have been overlooked for far too long, names the troublesome wife as Corr-dhu ("Black-Crane").

We might also note that the 9th-century Welsh monk known as Nennius described a "wonder" of Scotland in the form of "a valley in Angus, in which shouting is heard every Monday night; Glend Ailbe is its name, and it is not known who makes this noise."

Nennius's Glend Ailbe seems to be a corruption of the Gaelic word for a valley (glen) and the River Isla, or perhaps the Allaid or Hill of Alyth, which dominates the vale of Strathmore. The mysterious shouting in this "Valley of Sorrow" was reputedly heard ever Monday night. And we know from Aneirin's eye-witness account of Arthur's last battle that it came to an end on a Monday.

This is just some of the evidence for Arthur having fallen in the vicinity of Alyth. There is plenty more to come in The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - including descriptions of the Pictish symbol stones, found close to the site of that battle, which actually depict the Grail in use!

I'll let you know when the book is about to be published.

Monday, 2 June 2014

The Meaning of "Camlann"

I received a message from Moon Books today, telling me that the copyedited manuscript of The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion is ready for me to check.

It seems unlikely that the book will be available before the Scottish independence referendum in September. I'll be keeping a close eye on the referendum: the vote takes place the day before my 12th wedding anniversary, and having got married on the Isle of Iona to a woman who is half-Scottish, as well as having gone to university in Glasgow, my sympathies lie very much with the "YES" campaign.

I was also interested to note that Le Monde published this piece, indicating that the pro-independence campaign is gaining ground. The reporter had been in Alyth, Perthshire, to follow the debate. Alyth, as I revealed in The King Arthur Conspiracy, is where Arthur fought his last battle.

How do I know this? Lots of reasons, not least of all the fact that the place is name checked in a contemporary poem of the battle.

But wasn't Arthur's last battle fought at a place called Camlan?

Well, for a long while I wasn't so sure. Now, though, I know that it was - sort of - and I explain why in my forthcoming book on The Grail. But as that may not be out before the referendum, I hereby present this information as a gift to the "YES" campaign and in honour of a warrior who gave his life fighting for Scottish (and British) independence.

Many commentators refuse to accept that the place-name "Camlan" isn't Welsh. The fact that Camlan is the Gaelic name for the old Roman fortifications at Camelon, near Falkirk in central Scotland, means nothing to them. Arthur's "Camlan" was Welsh, and that's all it could have been.

Very silly - and utterly useless, in terms of trying to track down the site of that all-important battle. If it was a Welsh place-name, it would have meant something like "Crooked Valley", which really doesn't help us very much.

The first literary reference to "Camlann" comes in the Annales Cambriae ("Welsh Annals") which mention Gueith cam lann - the "Strife of Camlann". However, that reference cannot be traced back to an earlier date than the 10th century, hundreds of years after the time of Arthur. The contemporary sources make no mention of "Camlann", and so it may be that the name didn't come into use until many years after Arthur's last battle was fought there.

The earliest literary reference to anyone called Arthur concerns an individual named Artur mac Aedain. He was a son of Aedan mac Gabrain, who was "ordained" King of the Scots by St Columba in 574. Accounts of the ordination ceremony indicate that Arthur son of Aedan was present on that occasion, and that St Columba predicted that Arthur would not succeed his father to the Scottish throne but would "fall in battle, slain by enemies."

Those same accounts tell us that Columba's prophecy came true: Artur mac Aedain died in a "battle of the Miathi", which means that he was killed fighting the Picts of central Scotland.

The Irish Annals, which were compiled from notes made by the monks of Iona, inform us that the first recorded Arthur was killed in a "battle of Circenn", fought in about 594. Circenn was the Pictish province immediately to the north of the Tay estuary - broadly, Angus and the Mearns - which was indeed the territory of the "Miathi".

Circenn might have been Pictish territory, but the name of the province is Gaelic. It combines the word cir (meaning a "comb" or a "crest") and cenn, the genitive plural of a Gaelic noun meaning "head". An appropriate translation of Circenn would therefore be "Comb-heads".

The Miathi Picts, like their compatriots in the Orkneys, appear to have modelled their appearance on their totem animal, the boar. This meant that they shaved their heads in imitation of the boar's comb or crest - rather like the Mohawk tonsure, which we wrongly think of as a "Mohican". Indeed, whilst we assume that the term "Pict" derived from the Latin picti, meaning "painted" or "tattooed", there are grounds for suspecting that it was actually a corruption of pecten, the Latin for a "comb" (hence the Old Scots word Pecht, meaning "Pict").

So where does "Camlann" fit into all this?

After Arthur's death, much of southern and central Scotland was invaded by the Angles, those forerunners of the English. As a consequence, the Germanic language known as Northumbrian Old English was established in southern and central Scotland by the 7th century. It eventually became the dialect called Lowland Scots.

In the Scots dialect, came, kem and camb all meant "comb". And lan', laan and lann all meant "land".

The land in which Arthur's last battle had been fought - that is, the Pictish province of Angus - was soon speaking an early variant of the English language, or Lowland Scots. The fact that the Pictish province of Circenn was named after its "Comb-heads", those Miathi warriors who cut their hair to resemble a boar's comb or crest, meant that the place became known by its early English equivalent: "Comb-land" or Camlann.

This was not, of course, the name that Arthur and his warrior-poets would have used for the place. But then, the term "Camlann" didn't appear in any literary source for at least another three or four hundred years. By the time the Welsh annalist came to interpolate the "Camlann" entry into the Annales Cambriae, the location had become known by its Old English/Lowland Scots name. But that name was merely a variant of the older Gaelic name for the province - Circenn, or "Comb-heads".

And that is where the first recorded Arthur fell in battle, as St Columba had predicted. Not in England or Wales or Brittany, but in Angus in Scotland.

The province of the Pictish "Comb-heads". The region known as "Comb-land", cam lann.

It seems unlikely that the book will be available before the Scottish independence referendum in September. I'll be keeping a close eye on the referendum: the vote takes place the day before my 12th wedding anniversary, and having got married on the Isle of Iona to a woman who is half-Scottish, as well as having gone to university in Glasgow, my sympathies lie very much with the "YES" campaign.

I was also interested to note that Le Monde published this piece, indicating that the pro-independence campaign is gaining ground. The reporter had been in Alyth, Perthshire, to follow the debate. Alyth, as I revealed in The King Arthur Conspiracy, is where Arthur fought his last battle.

How do I know this? Lots of reasons, not least of all the fact that the place is name checked in a contemporary poem of the battle.

But wasn't Arthur's last battle fought at a place called Camlan?

Well, for a long while I wasn't so sure. Now, though, I know that it was - sort of - and I explain why in my forthcoming book on The Grail. But as that may not be out before the referendum, I hereby present this information as a gift to the "YES" campaign and in honour of a warrior who gave his life fighting for Scottish (and British) independence.

Many commentators refuse to accept that the place-name "Camlan" isn't Welsh. The fact that Camlan is the Gaelic name for the old Roman fortifications at Camelon, near Falkirk in central Scotland, means nothing to them. Arthur's "Camlan" was Welsh, and that's all it could have been.

Very silly - and utterly useless, in terms of trying to track down the site of that all-important battle. If it was a Welsh place-name, it would have meant something like "Crooked Valley", which really doesn't help us very much.

The first literary reference to "Camlann" comes in the Annales Cambriae ("Welsh Annals") which mention Gueith cam lann - the "Strife of Camlann". However, that reference cannot be traced back to an earlier date than the 10th century, hundreds of years after the time of Arthur. The contemporary sources make no mention of "Camlann", and so it may be that the name didn't come into use until many years after Arthur's last battle was fought there.

The earliest literary reference to anyone called Arthur concerns an individual named Artur mac Aedain. He was a son of Aedan mac Gabrain, who was "ordained" King of the Scots by St Columba in 574. Accounts of the ordination ceremony indicate that Arthur son of Aedan was present on that occasion, and that St Columba predicted that Arthur would not succeed his father to the Scottish throne but would "fall in battle, slain by enemies."

Those same accounts tell us that Columba's prophecy came true: Artur mac Aedain died in a "battle of the Miathi", which means that he was killed fighting the Picts of central Scotland.

The Irish Annals, which were compiled from notes made by the monks of Iona, inform us that the first recorded Arthur was killed in a "battle of Circenn", fought in about 594. Circenn was the Pictish province immediately to the north of the Tay estuary - broadly, Angus and the Mearns - which was indeed the territory of the "Miathi".

Circenn might have been Pictish territory, but the name of the province is Gaelic. It combines the word cir (meaning a "comb" or a "crest") and cenn, the genitive plural of a Gaelic noun meaning "head". An appropriate translation of Circenn would therefore be "Comb-heads".

The Miathi Picts, like their compatriots in the Orkneys, appear to have modelled their appearance on their totem animal, the boar. This meant that they shaved their heads in imitation of the boar's comb or crest - rather like the Mohawk tonsure, which we wrongly think of as a "Mohican". Indeed, whilst we assume that the term "Pict" derived from the Latin picti, meaning "painted" or "tattooed", there are grounds for suspecting that it was actually a corruption of pecten, the Latin for a "comb" (hence the Old Scots word Pecht, meaning "Pict").

So where does "Camlann" fit into all this?

After Arthur's death, much of southern and central Scotland was invaded by the Angles, those forerunners of the English. As a consequence, the Germanic language known as Northumbrian Old English was established in southern and central Scotland by the 7th century. It eventually became the dialect called Lowland Scots.

In the Scots dialect, came, kem and camb all meant "comb". And lan', laan and lann all meant "land".

The land in which Arthur's last battle had been fought - that is, the Pictish province of Angus - was soon speaking an early variant of the English language, or Lowland Scots. The fact that the Pictish province of Circenn was named after its "Comb-heads", those Miathi warriors who cut their hair to resemble a boar's comb or crest, meant that the place became known by its early English equivalent: "Comb-land" or Camlann.

This was not, of course, the name that Arthur and his warrior-poets would have used for the place. But then, the term "Camlann" didn't appear in any literary source for at least another three or four hundred years. By the time the Welsh annalist came to interpolate the "Camlann" entry into the Annales Cambriae, the location had become known by its Old English/Lowland Scots name. But that name was merely a variant of the older Gaelic name for the province - Circenn, or "Comb-heads".

And that is where the first recorded Arthur fell in battle, as St Columba had predicted. Not in England or Wales or Brittany, but in Angus in Scotland.

The province of the Pictish "Comb-heads". The region known as "Comb-land", cam lann.

Monday, 17 March 2014

My Writing Process (blog tour)

I was "tagged" to take part in this blog hop by the wonderful Margaret Skea, whom I have known since the Authonomy days, and who posted about her writing process on her own blog last week.

Margaret passed on to me the four questions that writers are invited to answer as part of this blog tour.

So, here goes ...

1. What am I working on?

Right now, I'm finishing one project and starting another. The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Tradition has been occupying my time now since January 2013. I was looking to do something of a follow up to The King Arthur Conspiracy, partly because I had been doing some more research - especially into the location and circumstances of Arthur's last battle - and partly because I wanted to address some of the (very minor) objections to Artuir mac Aedain having been the original Arthur of legend.

Thanks to Trevor Greenfield of Moon Books, I was given the opportunity to write The Grail in an unusual way. Each month, from January to December 2013, I would write a chapter, which would then by uploaded onto the Moon Books blog. That meant that, each month, I would send my draft chapter to my associate, John Gist, in New Mexico, who would read it and comment on it for me, and I would visit my friend Lloyd Canning, a local up-and-coming artist, to discuss the illustration that would accompany the chapter. There would be a final rewrite, and then I'd submit the chapter and the image to Trevor at Moon Books.

It was a long process, and an odd one (I wouldn't normally submit anything less than a complete manuscript). I've spent the last couple of months revising the full text and adding a few more illustrations. And, well, it's about finished. John contacted me from the States last night to say that he had read through one of the more recent drafts of the full thing and he really liked it. It's not all about the distant past - there's a lot about how our brains work, and how a certain type of mind tends to ruin history (and other things) for everybody else. That type of mindset seeks to prevent research into figures like Artuir mac Aedain so that the prevailing myth can be maintained. The same type of mindset will cause us no end of problems in the immediate future, and the book ends with something of a prediction.

Coming up ... Sir William Davenant. I published a piece on The History Vault, a couple of days ago, about Shakespeare's Dark Lady. It could be read as a sort of introduction to my biography of Sir William Davenant. I've only just signed the contract for the Davenant book, and it's due to be handed in to The History Press in June 2015.

2. How does my work differ from others of its genre?

History for me is an investigative process. I lose patience very quickly with historians who do nothing more than repeat what the last historian said. It's a major problem: a consensus arises, and woe betide any self-respecting historian who challenges that consensus. But the consensus is often based, not on historical facts, but on a kind of political outlook. It tends to be history-as-we-would-like-it-to-be, rather than history-as-it-was.

There are similarities with archaeology. Dig down anywhere within the Roman walls of the old city of London and you'll hit a layer of dark earth. This was left behind by Boudica when she and her Iceni warriors destroyed Londinium in about AD 60. But if you don't dig down far enough, you won't find that layer.

Too much history - certainly where Arthur (and the Grail) and Shakespeare (and Davenant) are concerned - gets down as far as one layer and stays there. In the case of Arthur, that layer is the 12th century; with Shakespeare, it's the late 18th century. In both instances, that's when the story changed. New versions of Arthur and Shakespeare arose, reflecting the obsessions of the particular era. When historians dig down to that layer, and report on what they've found, they're not writing about Arthur or Shakespeare - they're writing about what later generations wanted to think about Arthur and Shakespeare.

You have to go down further. Otherwise, you're just repeating propaganda.

I'm also a bit fussy about how my books read. That's my dramatist background, I reckon. But I read a great many books - history, mostly, of course - and too many of them are, frankly, boring. I seek to write exciting, accessible history that has been more diligently researched than the norm. I don't seek to shock, but real history often is shocking. Maybe that's why so many historians prefer to keep telling the "consensus" story.

3. Why do I write what I do?

The work I do now started because I was intrigued and inquisitive. The familiar legends of Arthur are all well and good, but I was more interested in the man who inspired them - who was he? what made him so special? And the same with Shakespeare - how did a Warwickshire lad become the greatest writer in the English language? (My own background is not too different from Shakespeare's.) And what was the inspiration for the character of Lady Macbeth.

I'm still intrigued and inquisitive, but over the years I've found myself more and more determined to see justice done - to right the wrongs of the past. Those wrongs are perpetuated by historians who don't ask questions. And that's a betrayal, not only of the actual subjects (Arthur, Shakespeare) but also of the reader today. It's a kind of cover-up, designed - I believe - to reshape the past so that it justifies certain policies today. If you're a monarchist, for example, or an old-fashioned imperialist, you're going to want to believe that Queen Elizabeth I was marvellous. And then you're going to have to believe that Shakespeare thought she was marvellous. Which means that you'll have to turn a blind eye to what was going on during her reign, and to the criticisms which Shakespeare voiced. Before you know it, you're ignoring the facts altogether in order to write a history that supports your own prejudices. I can't believe how often that happens.

Both Arthur and Shakespeare were killed, and their stories were subsequently written up by their enemies. Their real stories are much more interesting - and they deserve to be told. If we cling to the myths, we allow demagogues to dictate our history to us.

4. How does my writing process work?

Well, it's not quick. The research can take years. Then there are usually a number of false starts. Fortunately, I tend to have some sort of agreement with a publisher, these days, so when I say I'm going to write something, that means I have to get on with it.

I'll start at the beginning, with the long, slow process of getting words down on the page (it's long and slow because I have to go hunting for the information before I put it down). But I always have a carefully worked out structure in my mind, and day after day a kind of rough draft takes shape. It's usually fairly messy, and at some point I'll stop and go back to the start, smartening it up and giving myself enough momentum to plough on and get a few more chapters drafted.

After that, it's an ongoing process of revision (never less than three drafts). For several months, I'll be revising the early chapters while I'm still drafting the later ones.

I have to work pretty much every day. For a finished manuscript of, say, 100,000 words, I'll expect to write anything up to 500,000 words, which will be sifted and boiled down to fit the appropriate length. I'll keep going back and revising different sections, here and there, and often, in the latter stages, I'll rewrite the chapters out of sequence (partly to keep them all fresh). Then there's endless, obsessive tinkering, as I fuss over every full stop and comma.

The King Arthur Conspiracy took seven months to write (and rewrite). Who Killed William Shakespeare? took nine months, and then some for the illustrations. The Grail took me a year to write (a chapter a month) and another 2-3 months to revise (with illustrations). With Sir William Davenant I want to create something special, so that'll take ages.

There are two things I couldn't do without. One is coffee. The other is my fantastically loyal, supportive and organised wife, Kim.

*****

I now get to tag a couple of authors who will pick up the baton and run with it, and I've chosen two great writers who are part of the Review Group on Facebook. I'll let the first introduce herself:

I’m Louise Rule, my first book Future Confronted was published in December 2013, and I am now researching my next book, the story of which will take me travelling from Scotland to England, and then to Italy. I am on the Admin Team of the Facebook group The Review Blog which I enjoy immensely.

Louise's blog can be found here.

My other chosen successor on this blog tour is Stuart S. Laing. Stuart writes about Scottish history - his posts on the Review Group Blog covering fascinating moments in Edinburgh's past are a joy to read, but it's his historical novels - the Robert Young of Newbiggin Mysteries - which really deserve attention.

Stuart's blog can be found here.

Finally, it remains for me only to thank Margaret Skea for inviting me to take part in this hop. And to thank you, dear reader, for perusing my musings.

Ciao!

Margaret passed on to me the four questions that writers are invited to answer as part of this blog tour.

So, here goes ...

1. What am I working on?

Right now, I'm finishing one project and starting another. The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Tradition has been occupying my time now since January 2013. I was looking to do something of a follow up to The King Arthur Conspiracy, partly because I had been doing some more research - especially into the location and circumstances of Arthur's last battle - and partly because I wanted to address some of the (very minor) objections to Artuir mac Aedain having been the original Arthur of legend.

Thanks to Trevor Greenfield of Moon Books, I was given the opportunity to write The Grail in an unusual way. Each month, from January to December 2013, I would write a chapter, which would then by uploaded onto the Moon Books blog. That meant that, each month, I would send my draft chapter to my associate, John Gist, in New Mexico, who would read it and comment on it for me, and I would visit my friend Lloyd Canning, a local up-and-coming artist, to discuss the illustration that would accompany the chapter. There would be a final rewrite, and then I'd submit the chapter and the image to Trevor at Moon Books.

It was a long process, and an odd one (I wouldn't normally submit anything less than a complete manuscript). I've spent the last couple of months revising the full text and adding a few more illustrations. And, well, it's about finished. John contacted me from the States last night to say that he had read through one of the more recent drafts of the full thing and he really liked it. It's not all about the distant past - there's a lot about how our brains work, and how a certain type of mind tends to ruin history (and other things) for everybody else. That type of mindset seeks to prevent research into figures like Artuir mac Aedain so that the prevailing myth can be maintained. The same type of mindset will cause us no end of problems in the immediate future, and the book ends with something of a prediction.

Coming up ... Sir William Davenant. I published a piece on The History Vault, a couple of days ago, about Shakespeare's Dark Lady. It could be read as a sort of introduction to my biography of Sir William Davenant. I've only just signed the contract for the Davenant book, and it's due to be handed in to The History Press in June 2015.

2. How does my work differ from others of its genre?

History for me is an investigative process. I lose patience very quickly with historians who do nothing more than repeat what the last historian said. It's a major problem: a consensus arises, and woe betide any self-respecting historian who challenges that consensus. But the consensus is often based, not on historical facts, but on a kind of political outlook. It tends to be history-as-we-would-like-it-to-be, rather than history-as-it-was.

There are similarities with archaeology. Dig down anywhere within the Roman walls of the old city of London and you'll hit a layer of dark earth. This was left behind by Boudica when she and her Iceni warriors destroyed Londinium in about AD 60. But if you don't dig down far enough, you won't find that layer.

Too much history - certainly where Arthur (and the Grail) and Shakespeare (and Davenant) are concerned - gets down as far as one layer and stays there. In the case of Arthur, that layer is the 12th century; with Shakespeare, it's the late 18th century. In both instances, that's when the story changed. New versions of Arthur and Shakespeare arose, reflecting the obsessions of the particular era. When historians dig down to that layer, and report on what they've found, they're not writing about Arthur or Shakespeare - they're writing about what later generations wanted to think about Arthur and Shakespeare.

You have to go down further. Otherwise, you're just repeating propaganda.

I'm also a bit fussy about how my books read. That's my dramatist background, I reckon. But I read a great many books - history, mostly, of course - and too many of them are, frankly, boring. I seek to write exciting, accessible history that has been more diligently researched than the norm. I don't seek to shock, but real history often is shocking. Maybe that's why so many historians prefer to keep telling the "consensus" story.

3. Why do I write what I do?

The work I do now started because I was intrigued and inquisitive. The familiar legends of Arthur are all well and good, but I was more interested in the man who inspired them - who was he? what made him so special? And the same with Shakespeare - how did a Warwickshire lad become the greatest writer in the English language? (My own background is not too different from Shakespeare's.) And what was the inspiration for the character of Lady Macbeth.

I'm still intrigued and inquisitive, but over the years I've found myself more and more determined to see justice done - to right the wrongs of the past. Those wrongs are perpetuated by historians who don't ask questions. And that's a betrayal, not only of the actual subjects (Arthur, Shakespeare) but also of the reader today. It's a kind of cover-up, designed - I believe - to reshape the past so that it justifies certain policies today. If you're a monarchist, for example, or an old-fashioned imperialist, you're going to want to believe that Queen Elizabeth I was marvellous. And then you're going to have to believe that Shakespeare thought she was marvellous. Which means that you'll have to turn a blind eye to what was going on during her reign, and to the criticisms which Shakespeare voiced. Before you know it, you're ignoring the facts altogether in order to write a history that supports your own prejudices. I can't believe how often that happens.

Both Arthur and Shakespeare were killed, and their stories were subsequently written up by their enemies. Their real stories are much more interesting - and they deserve to be told. If we cling to the myths, we allow demagogues to dictate our history to us.

4. How does my writing process work?

Well, it's not quick. The research can take years. Then there are usually a number of false starts. Fortunately, I tend to have some sort of agreement with a publisher, these days, so when I say I'm going to write something, that means I have to get on with it.

I'll start at the beginning, with the long, slow process of getting words down on the page (it's long and slow because I have to go hunting for the information before I put it down). But I always have a carefully worked out structure in my mind, and day after day a kind of rough draft takes shape. It's usually fairly messy, and at some point I'll stop and go back to the start, smartening it up and giving myself enough momentum to plough on and get a few more chapters drafted.

After that, it's an ongoing process of revision (never less than three drafts). For several months, I'll be revising the early chapters while I'm still drafting the later ones.

I have to work pretty much every day. For a finished manuscript of, say, 100,000 words, I'll expect to write anything up to 500,000 words, which will be sifted and boiled down to fit the appropriate length. I'll keep going back and revising different sections, here and there, and often, in the latter stages, I'll rewrite the chapters out of sequence (partly to keep them all fresh). Then there's endless, obsessive tinkering, as I fuss over every full stop and comma.

The King Arthur Conspiracy took seven months to write (and rewrite). Who Killed William Shakespeare? took nine months, and then some for the illustrations. The Grail took me a year to write (a chapter a month) and another 2-3 months to revise (with illustrations). With Sir William Davenant I want to create something special, so that'll take ages.

There are two things I couldn't do without. One is coffee. The other is my fantastically loyal, supportive and organised wife, Kim.

*****

I now get to tag a couple of authors who will pick up the baton and run with it, and I've chosen two great writers who are part of the Review Group on Facebook. I'll let the first introduce herself:

I’m Louise Rule, my first book Future Confronted was published in December 2013, and I am now researching my next book, the story of which will take me travelling from Scotland to England, and then to Italy. I am on the Admin Team of the Facebook group The Review Blog which I enjoy immensely.

Louise's blog can be found here.

My other chosen successor on this blog tour is Stuart S. Laing. Stuart writes about Scottish history - his posts on the Review Group Blog covering fascinating moments in Edinburgh's past are a joy to read, but it's his historical novels - the Robert Young of Newbiggin Mysteries - which really deserve attention.

Stuart's blog can be found here.

Finally, it remains for me only to thank Margaret Skea for inviting me to take part in this hop. And to thank you, dear reader, for perusing my musings.

Ciao!

Friday, 10 January 2014

A Race Against Time

I came across this press piece a few days ago. It's maybe not quite as bad as it first appears: nobody seems to be suggesting that we build new houses on top of the Old Oswestry hill-fort, only on the fields immediately adjacent. But what I found most interesting about the article is what it says of the 3,000 year old hill-fort - that Old Oswestry is "said to be the birthplace of Guinevere, King Arthur's Queen."Ooops, let's back up a bit there. "Guinevere" is a medieval invention. Or, rather, it's a Medieval French rendition of a Welsh name - Gwenhwyfar. It's just one of those Arthurian anomalies that we keep referring to the original characters by the wrong names. Forget Guinevere: she didn't exist. Let's call her Gwenhwyfar instead.

And while we're at it, let's stop saying "King Arthur", because he didn't exist either. His people remembered him as "the emperor Arthur". Or we could just call him "Arthur". But "King Arthur" is purely mythical, even though Arthur himself was real.

Anyway, there is a tradition - apparently - that Gwenhwyfar, the wife of Arthur the Emperor, was born at Old Oswestry. I was quite thrilled to read that, because in "The King Arthur Conspiracy" I endeavoured to trace Gwenhwyfar's family background, and was able to pin it down to the Flintshire region of North Wales. Oswestry, on the Welsh border, is just to the south of that part of the world, and was quite possibly part of the sub-kingdom ruled by Gwenhwyfar's father.

I identified Gwenhwyfar's father as Caradog Freichfras ("Strong-Arm"), who was initially associated with the kingdom of Glywysing, immediately to the south of Oswestry. However, along with a number of other Arthurian heroes, Caradog seems to have shifted his base of operations northwards, initially to the Tegeingl sub-kingdom of Gwynedd, immediately to the north of (and possibly incorporating) Oswestry.

The Iron Age hill-fort believed to have been Gwenhwyfar's birthplace is also pretty close to the parish of Llangollen. This was home to an individual who became known as St Collen, although I argue that he was better known as (St) Cadog - another princeling of South Wales who moved, first into North Wales and, later, into central Scotland. Cadog - or Collen - appears to have functioned as a foster-father figure to Gwenhwyfar, or perhaps as the Druidic leader of her maidenly cult, and it is rather telling to discover that a Croes Gwenhwyfar - "Gwenhwyfar's Cross" - exists at Llangollen.

In other words, there is a fair amount of evidence which places the young Gwenhwyfar in the general area of Oswestry - before she, like so many of the others, moved north into what is now Scotland - and so we cannot write off the possibility that she was indeed born in the Iron Age hill-fort of Old Oswestry.

But that's not really the point of this post. Neither, for that matter, is any hand-wringing or soul-searching over the desirability of a new housing estate next door to Gwenhwyfar's birthplace - although that issue might serve as a sort of metaphor for what this post is all about.

It's about the race against time that we're currently in. Let me explain:

We live in unprecendented times. The internet, for example, is like nothing humanity that has ever known. So much knowledge at our fingertips! Researching Arthur and his people - and, for example, narrowing down the location of his last battle, as I did in The King Arthur Conspiracy and, in more detail, in my forthcoming The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - would have been immensely more time-consuming and expensive than it was.

However ... we also live in precedented times. I again cover this in The Grail, which is very much an exploration of the three "ages" of civilisation. We are currently being bullied out of the "Human age", which is characterised by liberal democracy and scientific materialism, by a resurgence of medieval "Heroic age" values, which we can characterise as dominated by religious fanaticism and extreme social inequality. This regression - the determination of some to tug us back into the kind of society which existed during the Middle Ages - is not really possible. It will lead (inevitably, I believe) to the collapse of our civilisation.

The internet is a fascinating product of our times. It is, in many ways, the ultimate "Human age" invention - possible only because of the technological infrastructure that was created by science, and thoroughly democratic, in that it is available to anybody. But the infrastructure necessary for the maintenance of a viable internet might not survive for long, and the anti-democratic instincts of those religious and political extremists who are forcing us back towards the "Heroic age" of times past are unlikely to favour the internet in its current form (although the internet is also one of the great purveyors of "Heroic age" thought, as uninformed opinion usurps the place of evidence-based logical reasoning and hysterical, paranoid memes spread like wildfire).

So, those of us who are fortunate enough to have access to the Global City which is the internet should really be using it to the best of our abilities. When it goes, it's gone - and our descendants will wonder at the race of supermen who could communicate instantaneously with millions across great distances, and who could access any information they required, just like that.

Do you really want your great-grandchildren to know that you had access to the greatest library the world has ever known, and the ability to exchange information with a massive global community - and all you did was post pictures of cats?

One of the ways in which the "Heroic age" is fighting back is through the rewriting of history. Michael Gove's cretinously empty-headed intervention in the matter of the First World War (which he seems to think was a rare old lark, sadly misreported ever since by "left-wing" academics and sit-com writers) shows that the religious-aristocractic view of the past, laced with ignorant flag-waving nationalism, is actively seeking to take control of history. Forget all those First World War poets who raged and railed against the hellish nightmare of the Western Front. No: a dimwitted politician now tells us that the war was a Good Thing, and anyone who questions that must be a "left-wing" radical.

In fact, the "Heroic age" has always rewritten history. It does so in order to cover its tracks and to pervert everyone's idea of the present. A government which is absolutely devoted to recreating the old aristocracy does not want you to think that the aristocratic officers of the First World War, or the aristocrats who sent so many millions to their deaths, were incompetent oafs. But the brainless attitude voiced by Michael Gove (Secretary of State for Education, would you believe?!) is symptomatic of a mindset that would happily send millions more to their deaths because they never learnt the lessons of history (how could they? Gove had already rewritten the book). And it's precisely that sort of thing that will undermine our civilisation.

Before we lose the internet, then - before we are banned from using it (because it's too democratic) or the infrastructure necessary to keep it going disintegrates (because it's "too expensive") - those of us who care about history really need to be making the most of our unprecedented opportunities to explore the past.

The "Heroic age" lied to us - repeatedly - about Arthur and his people. It was the "Heroic age" that invented the mythical "King Arthur" and changed the name of his wife from the authentic Gwenhwyfar to the familiar "Guinevere". And, let's face it, having lied to us before, it will lie to us again, given half a chance.

The only thing we can do is to uncover the historical truth, before the opportunity to do so is taken away from us. Arthur's last battle was fought at or near Alyth, in Scotland. A bit of determined research (internet and traditional) confirms this. But the "Heroic age" will have you believing that it happened somewhere else. Probably in the south. Evidence? Forget it. The "Heroic age" doesn't need evidence. It believes what it believes, and expects everyone else to believe it too. Evidence, be damned!

We could do our descendants a great big favour by using the internet intelligently, to challenge the foolish stories peddled by "Heroic age" propagandists. "King Arthur" never existed - he was an English invention - and the myth has always stood in the way of proper investigation. But tracing the historical Arthur is possible (and enjoyable), especially when we have all the resources of the internet at our command. Of course, the dogmatic voices of the "Heroic age" will shriek and shout and throw their little tantrums, but our great-grandchildren have the right to know what happened in the past. We have a duty to tell them, and not to let the past remain obliterated and re-engineered by fanatical demagogues, for whom everything must defend an extremist religious and/or political point-of-view.

So, in that sense, the story at the top of this post is a kind of metaphor. We are able - if we choose - to find out a great deal about Gwenhwyfar and her (possible) birthplace. But that won't last forever. Like the Iron Age hill-fort in which Arthur's wife was quite possibly born, there is a threat looming. The enemies of the truth are advancing.

There is still time to save the past from their bigoted opinions. But we do have to act.

Houses next door to Gwenhwyfar's birthplace? I'm not so worried about that, to be honest. Just so long as we succeed in uncovering and explaining who Gwenhwyfar was, while we still have the chance.

Tuesday, 15 October 2013

The Literary Medievalist

I just had to share this with you. A very good Facebook friend in Texas, DS Baker, who specialises in all things medieval, was kind enough to invite me to be the first author interviewed for his new blog.

I hope his new venture thrives and prospers! So please do pop over and have a look:

The Literary Medievalist

I hope his new venture thrives and prospers! So please do pop over and have a look:

The Literary Medievalist

Saturday, 12 October 2013

The New Heroic Age

A few posts back, I discussed the new Romeo and Juliet movie, for which Julian Fellowes wrote the screenplay.

Mr Fellowes "updated" Shakespeare's language to make it more "accessible". I queried whether Julian Fellowes was really the right choice for the job - he's not known for being down with the kids.

Well, Mr Fellowes has endeavoured to explain himself. Apparently, he feels that he's capable of understanding Shakespeare because he had a "very expensive education" and "went to Cambridge". Since most of us did not enjoy those advantages in life, it goes without saying that we are terminally thick and can only watch a Shakespeare play with our mouths open and our knuckles dragging on the ground.

In just a few words, Fellowes appears to have rendered the entire Shakespeare industry redundant. If you didn't go to private school and Oxbridge, the chances of you being able to "get" Shakespeare are nil. So the greatest dramatic works in the English Language become something that only the social elite can possibly appreciate. The rest of us have to make do with bookmarks, T-shirts, and "adaptations" which are written down to our educational level.

There's nothing new here. In the very first section of Who Killed William Shakespeare? I examine the intellectual (and social) snobbery of the late-18th century, which determined that the people of Shakespeare's hometown were congenitally stupid and only Londoners with money could comprehend the genius of the Bard (although, when it came to quoting him accurately, the metropolitan elite were rather lax).

So Julian Fellowes's excuses for wrecking Shakespeare's language are true to type. Basically, he's saying "I'm posh, you're not. Therefore, I can understand Shakespeare, while you're likely to struggle with the semiotic intricacies of Fifty Shades of Grey."

Now, bear with me here. I touched on the work of Giambattista Vico at the end of The King Arthur Conspiracy, but it's so important, so relevant, that I revisited Vico's theories very early on in The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion for Moon Books.

Giambattista Vico looked back across history and identified three major phases in the development of civilisations. The first, we might call the Divine age. This is essentially a primitive or indigenous society. The gods are all around us; we walk with them and talk with them, and everything we do is designed to appease them.

Then, certain individuals decide that they are descended from the gods. They lay claim to certain areas of land and found families or dynasties, which likewise claim direct descent from the gods. At about the same time, a priesthood appears which insists that it, and it alone, has access to those gods (or God). The priesthood and the aristocracy work hand in hand, claiming privileges which they deny to the rest of the populace. This, we might call the Heroic age.

Finally, the people wake up to the fact that they are every bit as human as their self-appointed masters. They demand an equal share in the decision-making process. We get democracy (and its corollary, scientific materialism). We might call this the Human age.

Okay, so far so good. We start out as "superstitious" primitives startled by thunder. We invent a single god, so that the more wealthy and powerful can claim that there is a divinely-ordained hierarchy which cannot be challenged. Then we discover Liberty, Egality and Fraternity.

But what happens next? Giambattista Vico was way ahead of his time, here. He recognised that all civilisations collapse. There is what he called a ricorso, a "return" to the start of the process. From the heights of science and democracy we are rather suddenly propelled back into a state of wonder at the world around us, reliant on the gods for everything.

What causes this ricorso? Dudley Young, in his wonderful Origins of the Sacred, suggested that democracy is inherently anarchic, and so a period of anarchy results in the demolition of democratic institutions and, inevitably, the end of civilisation. However, this theory is - I believe - fundamentally flawed.

What destroys civilisations is greed. Pure and simple. And how does that greed infect the carefully calibrated mechanisms of science and democracy? Easy: it does so by reinventing the Heroic age.

In other words, once a society has developed, progressing through the primitive/magical/theocratic Divine age and the religious-aristocratic Heroic age to the democratic and scientific systems of the Human age, a form of regression starts. Those who always preferred the certainties of the Heroic age (summed up, basically, as a landed aristocracy supported by the Church) begin to fight back against the principles of science and democracy. They start claiming more - much, much more - for themselves. And civilisation implodes under the weight of their regressive and selfish demands.

That is what is happening now. In many ways, we can replace the "Church" with "Corporate Capitalism", because they amount to the same thing. But anyone seeking enlightenment is recommended to read Naomi Klein's excellent, if chilling, The Shock Doctrine.

The post-war consensus - which was about as scientific and democratic as it is possible to be - began to crumble in the late 1970s. A small group of fanatical economists sought to undermine the certainties of the Human age. They argued that the State should have no involvement in everyday life. Everything should be in private hands. Their theories (mostly emanating from the Chicago School of Economics, which shall be forever cursed) could only be applied at the point of a gun. So a clever new step was invented. Naomi Klein called it "Disaster Capitalism".

Essentially, it works like this. A group of greedy individuals either invents or quickly moves to exploit a traumatic event (like a civil war, a tsunami or a perceived economic crisis). While the populace is too shocked to do anything about it, everything they thought they owned is transferred into private hands. The rich grow immensely richer. Everybody else suffers - and is tortured or "disappeared" if they dare to speak out.

No end of specious claims are made to justify these atrocities. Some of these are rather subtle, but they are all part of the ongoing conspiracy to steal from the people what the people once owned.

In cultural terms, we all own Shakespeare. And though a fairly decent level of education, and an awareness of history, are valuable in making sense of his rich words, there really is no barrier to anybody enjoying his works.

So the new aristocrats seek to claim him as exclusively their own. Only those who have enjoyed the Heroic age privileges of private education and automatic entry to Oxbridge can understand Shakespeare. He's not for the likes of you. He belongs to the rich and powerful.

Shakespeare himself would be utterly horrified by such a suggestion. He would be mortified. In fact, he would realise that he was being murdered all over again by such Heroic age fantasists as Mr Julian Fellowes.

(Consider this: Downton Abbey is a worldwide phenomenon, its success proof of the popularity of its cosy vision of the Heroic age in all its pompous finery. It hit our screens at about the same time as the most right-wing, privileged, "aristocratic" British government in living memory sneaked into office, and shortly before the Heroic age started flexing its muscles in the United States, where federal - i.e. democratic - government has been shut down by a bunch of Bible-bashing conservative fundamentalists from the Tea Party. In these regards, Downton Abbey is symptomatic of the New Heroic age, which covers up what its real agenda is by flogging us an attractively misleading story of the past.)

Science is under attack, these days (mostly from the fundamenalists of the religious-aristocratic school). So, too, is democracy - and the assaults are coming from the same direction: the New Heroic age. Call it jihad. Call it "Disaster Capitalism". Call it the New World Order. It's all the same.

It's the backwards-looking medievalism of the super-privileged eagerly driving us all back into a kind of feudalism. It's the special pleading of corporate lobbyists and uber-rich tax-avoiders. It's the old Etonians asserting their rule over the plebs. It is naked greed masquerading as the remedy to all our problems.

We must, must, must NOT allow such people to lionise William Shakespeare and his works. They might believe that they hold the exclusive rights to his memory - by dint of birthright and expensive upbringing - but they simply cannot be trusted with it.

Why? Because they don't understand him at all. They are only too quick to misrepresent him to us (see previous posts). They bend him to serve their own ends.

So Julian Fellowes has Downton Abbeyed Romeo and Juliet. He's selling you a false image of Shakespeare, one that surely suits his ideal of a New Heroic age in which the landed aristocracy - in cahoots with the Church of Corporate Wealth - look down from their charmless heights on the rest of us, who are just there to wash the dishes and make the beds for them (on zero-hour contracts, of course).

Remember the ricorso. If you want our civilisation to fall apart, that's the way to go. And everything Shakespeare was telling us will have gone unheeded, because we weren't considered capable of understanding him, and so we allowed our social "superiors" to interpret him for us.

And they lied. Because they always do.

Mr Fellowes "updated" Shakespeare's language to make it more "accessible". I queried whether Julian Fellowes was really the right choice for the job - he's not known for being down with the kids.

Well, Mr Fellowes has endeavoured to explain himself. Apparently, he feels that he's capable of understanding Shakespeare because he had a "very expensive education" and "went to Cambridge". Since most of us did not enjoy those advantages in life, it goes without saying that we are terminally thick and can only watch a Shakespeare play with our mouths open and our knuckles dragging on the ground.

In just a few words, Fellowes appears to have rendered the entire Shakespeare industry redundant. If you didn't go to private school and Oxbridge, the chances of you being able to "get" Shakespeare are nil. So the greatest dramatic works in the English Language become something that only the social elite can possibly appreciate. The rest of us have to make do with bookmarks, T-shirts, and "adaptations" which are written down to our educational level.

There's nothing new here. In the very first section of Who Killed William Shakespeare? I examine the intellectual (and social) snobbery of the late-18th century, which determined that the people of Shakespeare's hometown were congenitally stupid and only Londoners with money could comprehend the genius of the Bard (although, when it came to quoting him accurately, the metropolitan elite were rather lax).

So Julian Fellowes's excuses for wrecking Shakespeare's language are true to type. Basically, he's saying "I'm posh, you're not. Therefore, I can understand Shakespeare, while you're likely to struggle with the semiotic intricacies of Fifty Shades of Grey."

Now, bear with me here. I touched on the work of Giambattista Vico at the end of The King Arthur Conspiracy, but it's so important, so relevant, that I revisited Vico's theories very early on in The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion for Moon Books.

Giambattista Vico looked back across history and identified three major phases in the development of civilisations. The first, we might call the Divine age. This is essentially a primitive or indigenous society. The gods are all around us; we walk with them and talk with them, and everything we do is designed to appease them.

Then, certain individuals decide that they are descended from the gods. They lay claim to certain areas of land and found families or dynasties, which likewise claim direct descent from the gods. At about the same time, a priesthood appears which insists that it, and it alone, has access to those gods (or God). The priesthood and the aristocracy work hand in hand, claiming privileges which they deny to the rest of the populace. This, we might call the Heroic age.

Finally, the people wake up to the fact that they are every bit as human as their self-appointed masters. They demand an equal share in the decision-making process. We get democracy (and its corollary, scientific materialism). We might call this the Human age.

Okay, so far so good. We start out as "superstitious" primitives startled by thunder. We invent a single god, so that the more wealthy and powerful can claim that there is a divinely-ordained hierarchy which cannot be challenged. Then we discover Liberty, Egality and Fraternity.

But what happens next? Giambattista Vico was way ahead of his time, here. He recognised that all civilisations collapse. There is what he called a ricorso, a "return" to the start of the process. From the heights of science and democracy we are rather suddenly propelled back into a state of wonder at the world around us, reliant on the gods for everything.

What causes this ricorso? Dudley Young, in his wonderful Origins of the Sacred, suggested that democracy is inherently anarchic, and so a period of anarchy results in the demolition of democratic institutions and, inevitably, the end of civilisation. However, this theory is - I believe - fundamentally flawed.

What destroys civilisations is greed. Pure and simple. And how does that greed infect the carefully calibrated mechanisms of science and democracy? Easy: it does so by reinventing the Heroic age.

In other words, once a society has developed, progressing through the primitive/magical/theocratic Divine age and the religious-aristocratic Heroic age to the democratic and scientific systems of the Human age, a form of regression starts. Those who always preferred the certainties of the Heroic age (summed up, basically, as a landed aristocracy supported by the Church) begin to fight back against the principles of science and democracy. They start claiming more - much, much more - for themselves. And civilisation implodes under the weight of their regressive and selfish demands.

That is what is happening now. In many ways, we can replace the "Church" with "Corporate Capitalism", because they amount to the same thing. But anyone seeking enlightenment is recommended to read Naomi Klein's excellent, if chilling, The Shock Doctrine.

The post-war consensus - which was about as scientific and democratic as it is possible to be - began to crumble in the late 1970s. A small group of fanatical economists sought to undermine the certainties of the Human age. They argued that the State should have no involvement in everyday life. Everything should be in private hands. Their theories (mostly emanating from the Chicago School of Economics, which shall be forever cursed) could only be applied at the point of a gun. So a clever new step was invented. Naomi Klein called it "Disaster Capitalism".

Essentially, it works like this. A group of greedy individuals either invents or quickly moves to exploit a traumatic event (like a civil war, a tsunami or a perceived economic crisis). While the populace is too shocked to do anything about it, everything they thought they owned is transferred into private hands. The rich grow immensely richer. Everybody else suffers - and is tortured or "disappeared" if they dare to speak out.

No end of specious claims are made to justify these atrocities. Some of these are rather subtle, but they are all part of the ongoing conspiracy to steal from the people what the people once owned.

In cultural terms, we all own Shakespeare. And though a fairly decent level of education, and an awareness of history, are valuable in making sense of his rich words, there really is no barrier to anybody enjoying his works.

So the new aristocrats seek to claim him as exclusively their own. Only those who have enjoyed the Heroic age privileges of private education and automatic entry to Oxbridge can understand Shakespeare. He's not for the likes of you. He belongs to the rich and powerful.

Shakespeare himself would be utterly horrified by such a suggestion. He would be mortified. In fact, he would realise that he was being murdered all over again by such Heroic age fantasists as Mr Julian Fellowes.

(Consider this: Downton Abbey is a worldwide phenomenon, its success proof of the popularity of its cosy vision of the Heroic age in all its pompous finery. It hit our screens at about the same time as the most right-wing, privileged, "aristocratic" British government in living memory sneaked into office, and shortly before the Heroic age started flexing its muscles in the United States, where federal - i.e. democratic - government has been shut down by a bunch of Bible-bashing conservative fundamentalists from the Tea Party. In these regards, Downton Abbey is symptomatic of the New Heroic age, which covers up what its real agenda is by flogging us an attractively misleading story of the past.)

Science is under attack, these days (mostly from the fundamenalists of the religious-aristocratic school). So, too, is democracy - and the assaults are coming from the same direction: the New Heroic age. Call it jihad. Call it "Disaster Capitalism". Call it the New World Order. It's all the same.

It's the backwards-looking medievalism of the super-privileged eagerly driving us all back into a kind of feudalism. It's the special pleading of corporate lobbyists and uber-rich tax-avoiders. It's the old Etonians asserting their rule over the plebs. It is naked greed masquerading as the remedy to all our problems.