"Reekie Linn Waterfall, Angus" by stephen samson - Geograph http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/765407. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Reekie_Linn_Waterfall,_Angus.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Reekie_Linn_Waterfall,_Angus.jpg

*

Not all of the ancient stories about, or inspired by, the historical Arthur use the familiar name of the hero. Two alternative titles or designations which recur in this context are: Bran ("Raven") and Llew (Welsh: "Lion") or Lleu (Welsh: "Light"), the latter also occurring as Lliw or Llyw (Welsh: "Leader"), possibly from the Irish luige, Welsh llw, an "oath".

So let's look at some of the stories which give one or other of these names to their oh-so Arthurian heroes.

Le Chevalier Bran

Among the earliest sources for the "battle of Circenn" in which Arthur died, the Irish Annals of Tigernach name Bran as one of the sons of Aedan, King of the Scots, who fell alongside Artur/Artuir. The Annals of Ulster name Bran instead of Arthur. Adomnan's Life of Columba names Arthur instead of Bran.

In Welsh legend, Bran, the "Blessed Raven", was the "crowned king of the Island of Britain" who fell through the treachery of an Irish king named Matholwch ("Prayer-Sort"). The final battle involved a marvellous cauldron of rebirth, which had been Bran's gift to Matholwch. Along with Bran, who had been fatally wounded by a poisoned spear, there were just seven survivors of this epic battle. There were also seven survivors of Arthur's last battle, according to the contemporary poet and eye-witness, Taliesin.

Meanwhile, the "Horn of Bran the Hard from the North" was one of the Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain ("which were in the North"), the other treasures having belonged to the contemporaries, relatives and near-neighbours of Arthur son of Aedan. A later tradition holds that Arthur had a hound called Bran. The name evolved into the "Brons" of Arthurian romance.

Bearing all that in mind, I was fascinated to come across an old Breton folksong entitled Le Chevalier Bran ou le Prisonnier de Guerre ("The Horseman Bran, or the Prisoner of War"). Published in 1842, this song begins:

A la battaile de Kerlouan

Fut blesse le chevalier Bran!

A Kerlouan, sur l'ocean,

Le petit fils de Bran le Grand!

Prisonnier, bien que victorieux,

Il dont franchir l'ocean bleu.

["At the battle of Kerlouan, the horseman Bran was wounded! At Kerlouan, by the sea, the grandson of Bran the Great! Captured, even though he was victorious, he was taken across the sea."]

There is much that can be said about this intriguing song, with its distinct Arthurian overtones - for example, the song tells of an oak-tree which stands in the field of battle, at the spot where "the Saxons were put to flight when Even suddenly appeared", Even probably being Owain (French "Yvain") who distinguished himself at Arthur's last battle, as we know from Aneirin's epic Y Gododdin poem.

However, for now we need only concentrate on two aspects of the Breton song. The first is that le chevalier Bran was the grandson of Bran le Grand. The grandfather of Arthur son of Aedan was Gabran, the Scottish king who gave his name to the region of Gowrie, in which Arthur's last battle was fought.

What, then, of Kerlouan, where the horseman Bran was wounded and taken away as a "prisoner of war"? At first glance, it appears to refer to the commune of Kerlouan in the Finisterre department of Brittany. But this place-name almost certainly travelled with the British refugees who fled to Armorica, the "Lesser Britain", when their Lothian homelands were conquered by the Northumbrian Angles in circa AD 638. The ker element is cognate with the Welsh caer, meaning a "castle", "stronghold" or "citadel". The louan element refers to St Elouan, otherwise Luan, Llywan, Lua, Lughaidh or Moluag ("My-Luan").

St Elouan or Louan was an obscure saint, said to have been contemporary with St Columba (and, therefore, with Arthur son of Aedan) and to have brought Christianity to the northern, Highland Picts, while Columba spread the Gospel among the southern, "Miathi" Picts (Arthur son of Aedan died, according to the Life of Columba, in "the battle of the Miathi").

The only place where St Elouan or Louan is still venerated as "Luan" is at Alyth, near the site of Arthur's last battle. The Church of St Luan now stands on Alexander Street. The Alyth Arches are all that remain of an earlier church, dedicated to St Luan, which supposedly occupies the site of an even earlier chapel. Alyth, then, has a strong claim to have been the "Stronghold of Luan" or Kerlouan where Arthur/le chevalier Bran was grievously wounded and carried away "across the sea". Any resemblance to the Caerleon which recurs in Arthurian tradition as an early form of Arthur's legendary court (later "Camelot") is probably not coincidental.

Llew Skilful Hand

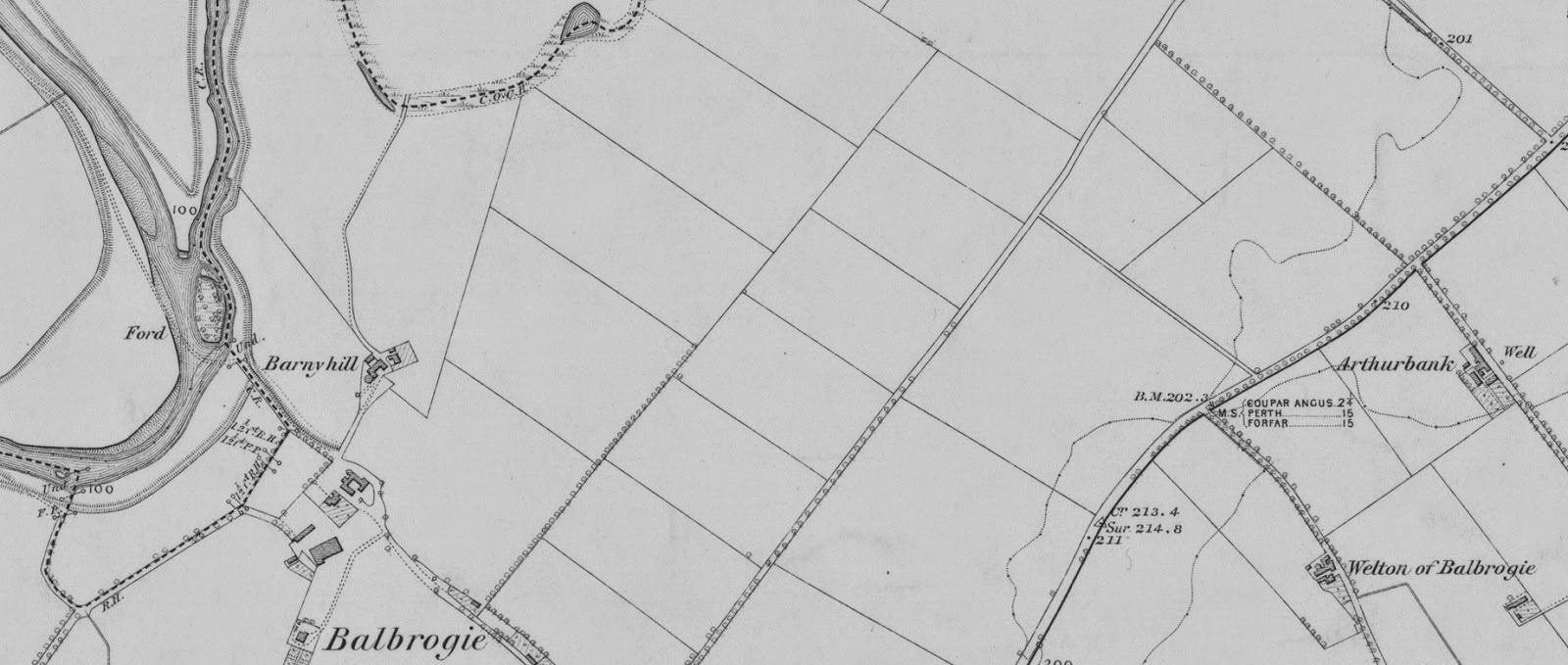

Llywan is the Welsh form of Luan/Louan. In the ancient Welsh tale of Culhwch and Olwen (which, as I stated in my previous blog post, offers a potted account of Arthur's career, including the violent seizure of a magical cauldron), the treacherous king-turned-boar is finally driven into a river near Llyn Lliwan ("Lake Louan"), which was somewhere near Tawy (the Tay). This lake appears to be remembered on the map of the Alyth area as the Bankhead and Kings of Kinloch, adjacent to Arthurbank beside the River Isla. The marshy ground in the river's floodplain was once known, perhaps, as Loch Luan, a name preserved in the spot, near Meigle, known as Glenluie.

The name of this lake recalls Llew, Lleu or Lliw - as Aneirin sang in his Y Gododdin elegy for the northern warriors who fell in Arthur's last battle:

No one living will relate what befell

Lliw, what came about on Monday at the Lliwan lake.

Apart from the tales of his Irish counterpart, Lugh Long-Hand, the most famous of the British legends concerning Llew or Lleu is that found in the Welsh "Mabinogion", in which a great hero known as Llew Skilful Hand is tricked by his treacherous wife into standing on the edge of a cauldron by a riverbank, where he is speared by his wife's lover (the poisoned spear took a year to make because it could only be worked on during the Mass on Sundays). The name given for the river on the banks of which Llew was speared is "Cynfael".

Now, bear with me here. The bloody boar-hunt in the legend of Culhwch and Olwen which culminates with the destruction of the Boar-King in the river near Loch Tay and the "Lliwan lake" is, in fact, the second of two dangerous boar-hunts which took place "in the North". The first concerned another Boar-King - or, to be more accurate, another king of the Miathi Picts, who modelled their appearance on the boar, hence the Gaelic and Scots names for their territory in Angus: Circenn ("Comb-heads") and Camlann ("Comb-land"). The death of this previous Boar-King of the Miathi Picts can be dated to circa AD 580, some 14 years before the final battle.

His name was Galam, although he went by a couple of epithets. The Annals of Ulster record the death of "Cennaleth, king of the Picts" in 580. The Annals of Tigernach refer to the death of "Cennfhaeladh king of the Picts" in the year 578.

These epithets reveal the location of Galam's power-base in Angus as king of the Miathi Picts. Cennaleth translates as "Chief of Alyth". Cennfhaeladh could indicate a "Shaved-head", as in the boar tonsure sported by the Miathi warriors, or the chief of a "high, rounded hill", such as that which looms over the town of Alyth in the vale of Strathmore. The proper pronunciation of Cennfhaeladh would be "ken-eye-la". This suggests that the name of the River Isla, which flows past Alyth and Arthurbank, derives phonetically from Cennfhaeladh. It also suggests that the Cynfael river, on the bank of which Llew Skilful Hand was treacherously speared by his wife's adulterous lover, was really the Cennfhaeladh or River Isla, on the bank of which Arthur was mortally wounded.

Arthur and his men defeated Galam Cennaleth ("Chief-of-Alyth"), otherwise Cennfhaeladh, in about 580 at the "Battle of Badon" (Gaelic Badain, the "Tufted Ones"), fought a little further up the River Isla at Badandun Hill. Galam's Miathi warriors later joined forces with Arthur's nemesis, Morgan the Wealthy, and the final conflict was fought beneath Barry Hill and the Hill of Alyth, on the banks of the River Isla or "Cynfael".

Seekers of the Grail - which in its earliest form was a magical cauldron - might care to investigate the legend of "Sir James" and his cauldron of enlightenment, a legend centred on the Reekie Linn waterfall, behind the Hill of Alyth (see top of this post). It's quite an eye-opener.