The Future of History

Sunday, 17 August 2014

Alyth, the Scene of Arthur's Last Battle

While I work on Shakespeare's Son - my biography of Sir William Davenant, a man of whom I'm becoming increasingly fond - The Grail continues to make its way through the publishing process, courtesy of Moon Books. So, by way of a sneak preview, in this post I shall offer up some of the evidence for the location of Arthur's last battle.

The Battle of Circenn

You probably think Arthur's last battle was fought at a place called "Camlann". I've been unable to find any reference to that place-name before the Middle Ages. The very earliest mentions of anyone called Arthur in the records indicate that he died in a battle fought in Angus, Scotland.

Adomnan of Iona's Life of Columba (circa 697) tells us that Artur son of Aedan was present when his father was "ordained" king of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574. The saint predicted the fates of Aedan's sons, announcing that Artur would "fall in battle, slain by enemies". Adomnan assured his readers that this prophecy came true when Artur and at least one of his brothers was killed in a "battle of the Miathi".

The Miathi, or Maeatae, were a Pictish tribe: essentially, they held the low-lying lands to the south and east of the Highland massif. Another Latinate term for these people was Verturiones.

The Irish annals, which drew at least some of their information from the records kept by Columba's monks on the Isle of Iona, specify that Artur son of Aedan died in a "battle of Circenn". This refers to the Pictish province which was roughly contiguous with today's Angus and the Mearns. The term Circenn combined the Gaelic cir, meaning a "comb" or "crest", and cenn, "heads". Circenn, then, was the land of the Comb-heads. This tells us that the Miathi Picts modelled their appearance on their totem beast, the boar (rather like their compatriots in the Orkneys, the Orcoi, from orc - a young boar). Indeed, it is possible that the Latinate name for the Verturiones tribe combines verres and turio and indicates the "offshoots" or "offspring" of the "boar", while the very term "Pict" (variant, "Pecti", "Pecht") quite possibly derived from the Latin pecten, a "comb".

Now, let's look at "Camlann" - the traditional name for Arthur's last battle. Its first appearance in the records comes in an entry interpolated into the Welsh Annals, where it refers to a gueith cam lann or "strife of cam lann". By the time this came to be written down, the region in which Artur son of Aedan died was speaking a version of Northumbrian Old English which became the dialect known as Lowland Scots. In that dialect, cam lann would mean "comb land".

In other words, "Camlann" is merely an anglicised version of the Gaelic Circenn, the land of the "Comb-heads" in which the first Arthur on record fell in a cataclysmic battle.

Culhwch and Olwen

One of the oldest of the Welsh (i.e. British) tales to feature Arthur is that of Culhwch ac Olwen. It forms a sort of mythologised, potted account of Arthur's career, culminating in the desperate and bloody hunt for a king who - for his sins - was turned into a boar. This hunt begins with a violent amphibious landing, at a site which can be identified as Cruden Bay, on the Aberdeenshire coast, after which Arthur is met by the "saints of Ireland" who "besought his protection". The dreadful Boar-King is challenged and chased from Esgeir Oerfel, the "Cold Ridge" of the Grampians, the Boar-King making his way across country towards Llwch Tawy (Loch Tay) before he is intercepted by Arthur and his men and driven into a river.

In The King Arthur Conspiracy I identified the treacherous Boar-King as Morgan the Wealthy, a renegade British prince who abducted Arthur's wife, Gwenhwyfar, and escaped into the land of the Miathi Picts (his bolt hole appears to have been the fortified Hill of Tillymorgan in Strathbogie). The site where Morgan finally came to grief is marked by the "Morganstone" on the west bank of the River Ericht, a short distance to the west of the Hill of Alyth in the great vale of Strathmore in Angus.

Arthurian Connections with Alyth

Before we proceed, let us consider some ancient references to Arthur and his family in the context of Alyth and its immediate vicinity.

In addition to having a son named Artur or Artuir, King Aedan of the Scots had a daughter called Muirgein. According to Whitley Stokes, editing and translating the Martyrology of a 9th-century Irish monk called Oengus, Muirgein daughter of Aedan was born "in Bealach Gabrain".

The inability of certain scholars to find a "Bealach Gabrain" in Scotland has led some to argue that Muirgein daughter of Aedan was utterly unconnected with Artur son of Aedan. But place-names evolve. The Gaelic term bealach, meaning a "pass" or "gorge", usually appears as "Balloch" on today's maps. There is a "Balloch" which runs along the feet of Barry Hill and the adjacent Hill of Alyth in Strathmore.

Furthermore, this "Balloch" or bealach was in a region named after the grandfather of Artur and Muirgein. Gabran was the father of Aedan. He ruled the Scots for twenty years until his death in about AD 559 and gave his name to the region of Gowrie (a corruption of Gabran). The "Balloch" near Alyth was in Gabran's land (Gabrain) and lies close to the town of Blairgowrie, which also recalls the name of Arthur's grandfather. The "Balloch" at the foot of the Hill of Alyth was almost certainly the "Bealach Gabrain" or "pass of Gowrie" where Arthur's (half-)sister, Muirgein daughter of Aedan mac Gabrain, was born. To pretend that the Balloch of Gowrie could not have been "Bealach Gabrain" because they are not spelled the same way these days is tantamount to claiming that Londinium and London could not have been the same place.

So Arthur's sister, Muirgein (latterly, Morgan le Fay), was born near Alyth. Writing in about 1527, the Scottish historian Hector Boece also indicated that Arthur's wife was buried at Meigle, which is just a mile or two south of Alyth. Hector Boece's local tradition recalled Gwenhwyfar as Vanora (via Guanora) and claimed that she had been held hostage in the Iron Age hill-fort atop Barry Hill, adjacent to the Hill of Alyth, before she was executed and buried in what is now the kirkyard at Meigle. A carved Pictish standing stone, now on display at the Meigle museum, reputedly depicts the execution or burial of Arthur's wife.

Y Gododdin

One of the best sources of information about Arthur's last battle is the ancient epic, Y Gododdin. This was composed and sung by Aneirin, a British bard of the Old North, and can be dated to circa AD 600 (the date of Arthur's last battle is given in the Irish annals as, variously, AD 594 and 596).

Unfortunately, the relevance of Aneirin's elegiac tribute to the warriors of Lothian (the "Gododdin") has been missed by scholars who want to believe that the poem bemoans the destruction of a British war-band from the Edinburgh area which had the misfortune to be wiped out at a mythical battle fought at Catterick in North Yorkshire. No evidence exists that any such battle was fought. The Angles (forerunners of the English) preferred not to recollect their defeats but were happy to remember, and to boast about, their victories. If the Angles of Northumbria had indeed obliterated a British band of heroes from Lothian at Catterick, we might assume that they would have remembered doing so. And no scholar has yet explained the presence of "Irishman and Picts" at this imaginary battle in Anglian territory.

A verse or two of Y G[ododdin, added at a later date than the original composition, described a battle fought in Scotland (Strathcarron) in AD 642 and the death in that battle of a Scottish king who just happened to be a nephew of Artur son of Aedan. This interpolation does at least suggest that the subject of the original poem was a battle fought in roughly the same area (Scotland) by the family of Artur and his father Aedan. The Y Gododdin poem also mentions various famous warriors who appear in the early accounts of Arthur's career and who were contemporary with Artur son of Aedan.

One surviving version of Y Gododdin even mentions Artur/Artuir by name:

Gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef Arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

Confused by the misidentification of the battle sung about by Aneirin in Y Gododdin, and the assumption that Arthur himself could not have been present at that battle, scholars have persistently mistranslated this verse - mostly in an attempt to render the second half of the second line, "He was no Arthur". But Aneirin's verse should properly be translated thus:

Black ravens [warriors] sang in praise of the hero [Welsh, arwr]

of Circenn [transliterated into Welsh as "caer ceni"]. He blamed Arthur;

the dogs cursed in return for our wailing/lamentation ...

Aneirin indicated, in his Y Gododdin elegy, precisely where the final battle took place:

Eil with gwelydeint amallet

y gat veirch ae seirch greulet

bit en anysgoget bit get ...

Which translates as:

Again they came into view around the alled,

the battle-horses and the bloody armour,

still steadfast, still united ...

The "alled" was Aneirin's Welsh-language attempt at the Gaelic Allaid - also Ailt - or the Hill of Alyth.

Breuddwyd Rhonabwy

The extraordinary medieval Welsh tale of The Dream of Rhonabwy actually provides a description of the scene in the hours before Arthur's last battle was fought. The visionary seer, Rhonabwy, finds himself crossing a great plain with a river running through it (Strathmore). He is met by a character call Iddog, "Churn of Britain", who admits that it was he who caused the cataclysmic "battle of Camlan" by betraying Arthur. In company with Iddog, Rhonabwy approaches the "Ford of the Cross" (Rhyd-y-Groes) on the river. A great army is encamped on either side of the road and Arthur is seated on a little flat islet in the river, beside the ford.

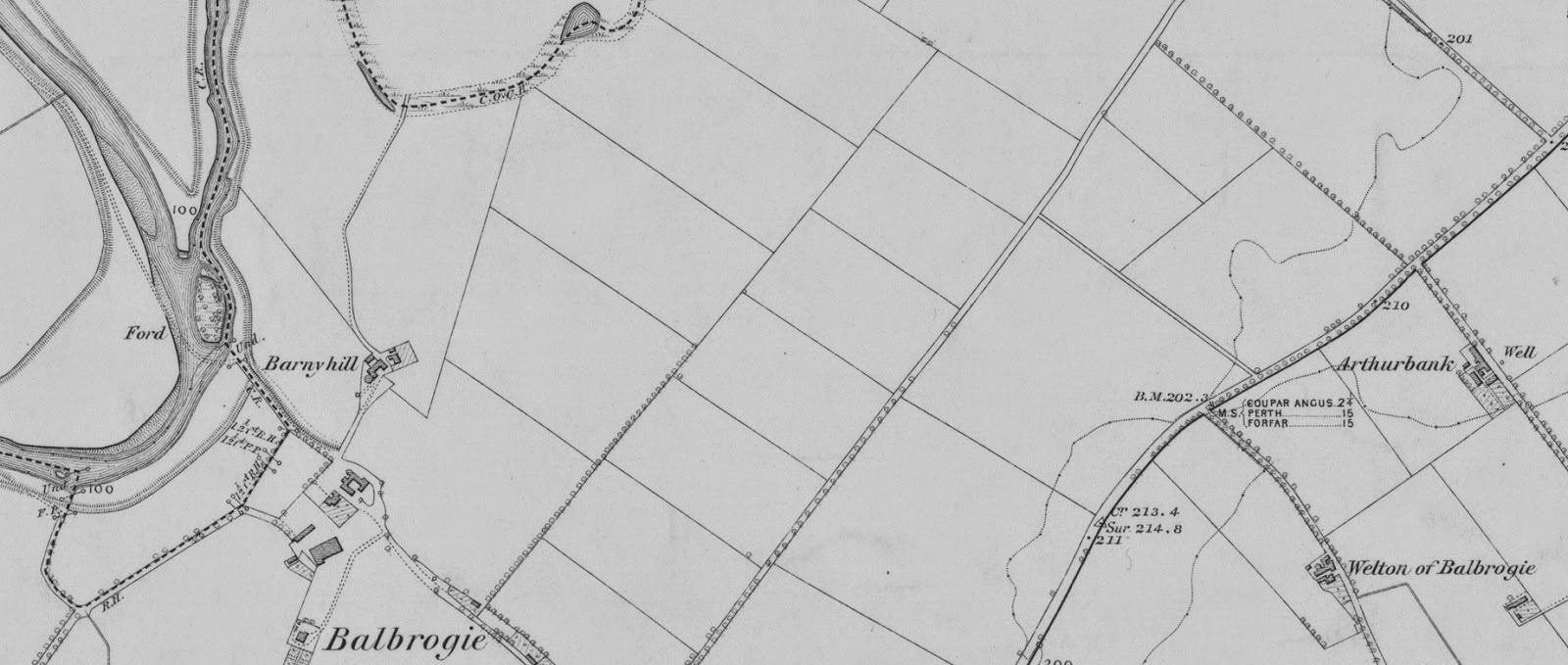

The topography precisely matches the detail from a 19th-century Ordnance Survey map of the area around Alyth seen at the top of this post. On the right-hand side of the detail is the ridge known as Arthurbank, which lies along the River Isla, opposite the junction of the River Ericht with the River Isla (a few miles down the Ericht from the site of the Morganstone). A little flat islet lies in the River Isla, close to the Arthurbank shore, and a ford runs alongside this little islet, exactly as described in the Welsh account of Rhonabwy's dream.

Aneirin also mentioned this ford in his Y Gododdin poem as rhyd benclwyd - the "ford" of the "grey" or "holy mount". There is, indeed, a Greymount marked on the map, a short distance to the north of the ford on the Isla. In his Agriculture of Perthshire, published in 1799, the Rev. Dr Robertson described the discovery of a "large Druidical temple" at Coupar Grange, adjacent to this ford. A standing stone found in this "temple" would no doubt have been rebranded a "cross" by the early Christians, so that the ford across the Isla, beside the little flat islet, would have become known as the Ford of the Cross (Rhyd-y-Groes), as described in The Dream of Rhonabwy, or the "Ford of the Grey/Holy Mount" (rhyd benclwyd) as described by Aneirin.

Until the late 18th century, an Arthurstone stood at the south-eastern edge of the Arthurbank ridge (its presence is still marked on the map). This Arthurstone corresponds to the Morganstone, a few miles away up the River Ericht, and marks the spot where Arthur fell in his battle with the Boar-King of the Miathi Picts in the land of the "crested" Comb-heads, Camlann.

The Head of the Valley of Sorrow

After the battle, Arthur's wife Gwenhwyfar was executed and buried only a mile or so away at Meigle. The legend of Culhwch and Olwen (which, interestingly, features a treacherous individual identified as Grugyn, who also appears in Aneirin's Y Gododdin) tells us that, after the battle at the river with the dangerous Boar-King, Arthur and his heroes once more "set out for the North" to overcome a fearsome witch. She was found inside a cave at Penn Nant Gofid - the "Head of the Valley of Sorrow"- on "the confines of Hell" (which we can interpret as the edge of the territory controlled by those boar-like Miathi Picts). The Welsh gofid ("sorrow/trouble/affiction/grief") appears to have been something of a pun, for another Welsh word for sorrow or grief is alaeth (compare Ailt, Allaid and Alyth, the "Head of the Valley of Alyth" being the very hill on which Arthur's wife is rumoured to have been held prisoner before her execution and burial nearby at Meigle).

In the Welsh tale, this witch is known as Orddu (that is, Gorddu - "Very Black"). A similar legend from the Isle of Mull, whose Arthurian associations have been overlooked for far too long, names the troublesome wife as Corr-dhu ("Black-Crane").

We might also note that the 9th-century Welsh monk known as Nennius described a "wonder" of Scotland in the form of "a valley in Angus, in which shouting is heard every Monday night; Glend Ailbe is its name, and it is not known who makes this noise."

Nennius's Glend Ailbe seems to be a corruption of the Gaelic word for a valley (glen) and the River Isla, or perhaps the Allaid or Hill of Alyth, which dominates the vale of Strathmore. The mysterious shouting in this "Valley of Sorrow" was reputedly heard ever Monday night. And we know from Aneirin's eye-witness account of Arthur's last battle that it came to an end on a Monday.

This is just some of the evidence for Arthur having fallen in the vicinity of Alyth. There is plenty more to come in The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - including descriptions of the Pictish symbol stones, found close to the site of that battle, which actually depict the Grail in use!

I'll let you know when the book is about to be published.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment