Well, there's already been an encouraging comment - I suppose you could call it an endorsement - on The Grail: Relic of an Ancient Religion from the all-round Arthurian expert John Matthews:

"A brisk rattle through the well-worn paths of the Grail and King Arthur. Some challenging new theories, applied with a kind of relish reminiscent of Robert Graves, make this a fascinating book."

I'd call that praise. And now, this new review has just been published on the Radical Goddess Thealogy blog.

Definitely worth a read!

The Future of History

Showing posts with label Moon Books. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Moon Books. Show all posts

Monday, 20 April 2015

Friday, 3 April 2015

Breaking the Mother Goose Code

A strange conversation on Facebook, the other day.

Somebody I sort of know had put up a post demanding that we all boycott Cadburys because they're selling "Halal Easter eggs".

Now, the idea of halal chocolate was a new one on me, so I thought I'd check it out. What had actually happened was this: Cadburys had put up a page on their website, indicating which of their many products are "halal certified". In other words, it's essentially dietary guidance - a bit like listing which Cadburys products are "Suitable for vegetarians". There was nothing "halal" about any of it, just a page letting Muslims know which Cadburys chocolate bars and so on are okay for them to eat.

I pointed this out. But, no, that wasn't good enough. Because, apparently, Easter eggs are Christian and so, by making them "halal" Cadburys were pandering to the Islamists and helping to sell Britain downriver.

So I came back - no religious text, to the best of my knowledge, refers to chocolate eggs and no religion has a monopoly on them (let's face it, God neglected to let most of the world know that chocolate even existed until comparatively recently). But I was wrong, it seems, because the word Easter in front of "eggs" makes them Christian, and exclusively so. And I was apparently attacking my friend's religion, which was a big No-No. And that's when I explained that "Easter" comes from "Eostre", a pagan goddess - which explains the eggs, bunnies, chicks and other Eastery thingies. There's no "Easter" in the Bible, only Passover.

And there endeth the Facebook friendship.

Which brings me to the subject of this post. I was very keen to read Jeri Studebaker's Breaking the Mother Goose Code - How a Fairy-Tale Character Fooled the World for 300 Years, partly because it looked interesting, and partly because my theatrical hero - Joey Grimaldi, King of Clowns - appeared in the first modern pantomime, Harlequin and Mother Goose; or, the Golden Egg, which did great business when it hit the stage at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, in December 1808.

I wondered - just wondered - whether Jeri Studebaker might mention the Mother Goose pantomime in her book. And I was not disappointed. Jeri had done her homework.

The first part of Breaking the Mother Goose Code really does focus on the character of Mother Goose, drawing attention to the similarities between this alternately beautiful and grotesque figure and certain ancient European mother-goddesses, especially Holda-Perchta. The second half takes the argument further, beyond Mother Goose herself, to examine the ways in which so-called "fairy tales" function as a kind of oral memory of the time when Goddess worship was widespread (and largely uncontested), and how these fairy tales - especially when shorn of their latter-day accretions - can be thought of as shamanic journeys and/or magical rituals and spells.

The idea, overall, is that patriarchy is a fairly new phenomenon. And it's a stinker. Whenever and wherever it appears, it pursues a sort of scorched earth policy. But people - whole populaces - don't just alter everything they believe overnight because an angry man tells them to. Those pre-patriarchal belief systems were natural and hardwired into our collective psyche. In the face of barbaric violence and blanket intolerance, the old ways lived on - surreptitiously - and did so, partly, through the transmission of fairy tales.

I like this idea. Mainstream history has been rather naughty, I feel, in taking such a dismissive and lofty attitude towards "folk" history (local legends, place-names, fairy tales). Just because these things weren't written down till a late stage, doesn't mean that they don't provide us with important glimpses of ancient knowledge. The Australian aboriginal sang the world back into existence with his song-lines, re-making the landscape by telling its stories, long before the White Man arrived to tell him he'd got it all wrong, and then make a slave of him.

Jeri Studebaker's research for this book is ample and impressive. She really knows her subject and has gone into it in great depth, producing a book that is both readable and stimulating. Hard facts mingle with interesting theories and speculations. And nowhere, I feel, is Jeri at her best more than when she is taking a wrecking-ball to patriarchy.

The differences between patriarchy (recent, bloody) and pre-patriarchal societies (been around for ever, generally equitable and non-violent) are brought out in such a way as to illustrate, not only what a disaster patriarchal structures have been for the species and the planet, but what we lost when we allowed our more natural societies to be steamrollered by the maniacs of patriarchal thinking. So many lives lost. So much wisdom lost. So much damage done.

In fact, Studebaker doesn't belabour this point, but chooses her examples carefully, citing experts in these matters. Her argument - that fairy tales like Mother Goose represent a sort of quiet resistance, a continuation of pre-patriarchal values in a time of patriarchal thuggery - grows, little by little, from her near-forensic analysis of Mother Goose (Holda-Perchta) herself to the wider world of fairy tales and their magical methodology - until, in my case at least, I was convinced. Strip away the Disneyfication, and fairy tales really can take us back to a pre-patriarchal age of equality and possibilities.

For an illustration of how disgusting and despicable patriarchal thinking can be, one has only to consider that online run-in with my "friend" over the matter of halal chocolate eggs. The intolerance, the ignorance, the "I can attack anybody's religion if I choose, but nobody can attack mine!" attitude (even though nobody was actually attacking her Christian faith) and that vague sense of a call-to-arms, a sort of "Let's have another crusade" subtext, are all indicative of patriarchal thinking. It is crude, divisive, and usually ends in tears.

Mother Goose and her fellows, as Jeri Studebaker shows in her rather wonderful book, can show us that it doesn't have to be like that. The Golden (Easter) Egg has nothing to do with Christianity, and those who squabble over it - "I can have it, you can't!" - are infantile and deluded. The Egg was delivered by Mother Goose, the Eternal Feminine, and we can all have it, if we're prepared to play the game.

Click here to go to the Moon Books page for Breaking the Mother Goose Code.

Somebody I sort of know had put up a post demanding that we all boycott Cadburys because they're selling "Halal Easter eggs".

Now, the idea of halal chocolate was a new one on me, so I thought I'd check it out. What had actually happened was this: Cadburys had put up a page on their website, indicating which of their many products are "halal certified". In other words, it's essentially dietary guidance - a bit like listing which Cadburys products are "Suitable for vegetarians". There was nothing "halal" about any of it, just a page letting Muslims know which Cadburys chocolate bars and so on are okay for them to eat.

I pointed this out. But, no, that wasn't good enough. Because, apparently, Easter eggs are Christian and so, by making them "halal" Cadburys were pandering to the Islamists and helping to sell Britain downriver.

So I came back - no religious text, to the best of my knowledge, refers to chocolate eggs and no religion has a monopoly on them (let's face it, God neglected to let most of the world know that chocolate even existed until comparatively recently). But I was wrong, it seems, because the word Easter in front of "eggs" makes them Christian, and exclusively so. And I was apparently attacking my friend's religion, which was a big No-No. And that's when I explained that "Easter" comes from "Eostre", a pagan goddess - which explains the eggs, bunnies, chicks and other Eastery thingies. There's no "Easter" in the Bible, only Passover.

And there endeth the Facebook friendship.

Which brings me to the subject of this post. I was very keen to read Jeri Studebaker's Breaking the Mother Goose Code - How a Fairy-Tale Character Fooled the World for 300 Years, partly because it looked interesting, and partly because my theatrical hero - Joey Grimaldi, King of Clowns - appeared in the first modern pantomime, Harlequin and Mother Goose; or, the Golden Egg, which did great business when it hit the stage at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, in December 1808.

I wondered - just wondered - whether Jeri Studebaker might mention the Mother Goose pantomime in her book. And I was not disappointed. Jeri had done her homework.

The first part of Breaking the Mother Goose Code really does focus on the character of Mother Goose, drawing attention to the similarities between this alternately beautiful and grotesque figure and certain ancient European mother-goddesses, especially Holda-Perchta. The second half takes the argument further, beyond Mother Goose herself, to examine the ways in which so-called "fairy tales" function as a kind of oral memory of the time when Goddess worship was widespread (and largely uncontested), and how these fairy tales - especially when shorn of their latter-day accretions - can be thought of as shamanic journeys and/or magical rituals and spells.

The idea, overall, is that patriarchy is a fairly new phenomenon. And it's a stinker. Whenever and wherever it appears, it pursues a sort of scorched earth policy. But people - whole populaces - don't just alter everything they believe overnight because an angry man tells them to. Those pre-patriarchal belief systems were natural and hardwired into our collective psyche. In the face of barbaric violence and blanket intolerance, the old ways lived on - surreptitiously - and did so, partly, through the transmission of fairy tales.

I like this idea. Mainstream history has been rather naughty, I feel, in taking such a dismissive and lofty attitude towards "folk" history (local legends, place-names, fairy tales). Just because these things weren't written down till a late stage, doesn't mean that they don't provide us with important glimpses of ancient knowledge. The Australian aboriginal sang the world back into existence with his song-lines, re-making the landscape by telling its stories, long before the White Man arrived to tell him he'd got it all wrong, and then make a slave of him.

Jeri Studebaker's research for this book is ample and impressive. She really knows her subject and has gone into it in great depth, producing a book that is both readable and stimulating. Hard facts mingle with interesting theories and speculations. And nowhere, I feel, is Jeri at her best more than when she is taking a wrecking-ball to patriarchy.

The differences between patriarchy (recent, bloody) and pre-patriarchal societies (been around for ever, generally equitable and non-violent) are brought out in such a way as to illustrate, not only what a disaster patriarchal structures have been for the species and the planet, but what we lost when we allowed our more natural societies to be steamrollered by the maniacs of patriarchal thinking. So many lives lost. So much wisdom lost. So much damage done.

In fact, Studebaker doesn't belabour this point, but chooses her examples carefully, citing experts in these matters. Her argument - that fairy tales like Mother Goose represent a sort of quiet resistance, a continuation of pre-patriarchal values in a time of patriarchal thuggery - grows, little by little, from her near-forensic analysis of Mother Goose (Holda-Perchta) herself to the wider world of fairy tales and their magical methodology - until, in my case at least, I was convinced. Strip away the Disneyfication, and fairy tales really can take us back to a pre-patriarchal age of equality and possibilities.

For an illustration of how disgusting and despicable patriarchal thinking can be, one has only to consider that online run-in with my "friend" over the matter of halal chocolate eggs. The intolerance, the ignorance, the "I can attack anybody's religion if I choose, but nobody can attack mine!" attitude (even though nobody was actually attacking her Christian faith) and that vague sense of a call-to-arms, a sort of "Let's have another crusade" subtext, are all indicative of patriarchal thinking. It is crude, divisive, and usually ends in tears.

Mother Goose and her fellows, as Jeri Studebaker shows in her rather wonderful book, can show us that it doesn't have to be like that. The Golden (Easter) Egg has nothing to do with Christianity, and those who squabble over it - "I can have it, you can't!" - are infantile and deluded. The Egg was delivered by Mother Goose, the Eternal Feminine, and we can all have it, if we're prepared to play the game.

Click here to go to the Moon Books page for Breaking the Mother Goose Code.

Monday, 23 March 2015

Gods of the Solar Eclipse

Naughty me. I should have posted this a couple of days ago.

It's a post I wrote for the Moon Books blog, timed to coincide with last Friday's eclipse.

Click here to read it: Gods of the Solar Eclipse.

It's a post I wrote for the Moon Books blog, timed to coincide with last Friday's eclipse.

Click here to read it: Gods of the Solar Eclipse.

Thursday, 12 March 2015

Mind Body Spirit

Just because you haven't heard a lot from me lately, doesn't mean I've not been busy.

Quite the reverse, in fact. Interesting research trips to Oxford and Bristol for my biography of Sir William Davenant (nearing completion), lecturing at the University of Worcester, Shakespeare Tours and Ghost Tours in Stratford-upon-Avon, and a new project which I'm not going to tell you about.

But - hold your horses, folks, because it looks like there might be a fair few blog posts in the offing. The Grail is out, later this month. Indeed, a correspondent in Washington State has already posted a photo on Facebook showing his pre-ordered copy, which arrived by post today. So it's kind of out there already.

And here's my first guest blog post on the subject, courtesy of the wonderful Mind Body Spirit Magazine.

More to come ...

Quite the reverse, in fact. Interesting research trips to Oxford and Bristol for my biography of Sir William Davenant (nearing completion), lecturing at the University of Worcester, Shakespeare Tours and Ghost Tours in Stratford-upon-Avon, and a new project which I'm not going to tell you about.

But - hold your horses, folks, because it looks like there might be a fair few blog posts in the offing. The Grail is out, later this month. Indeed, a correspondent in Washington State has already posted a photo on Facebook showing his pre-ordered copy, which arrived by post today. So it's kind of out there already.

And here's my first guest blog post on the subject, courtesy of the wonderful Mind Body Spirit Magazine.

More to come ...

Sunday, 4 January 2015

2015

Hello, Happy New Year, and welcome!

It had occurred to me to write up a review of 2014 and the various things that happened last year - from publishing my first university paper on The Faces of Shakespeare to the publication, in September, of Naming the Goddess, in which I have an essay (tweet received this morning from Michigan: 'Loved your essay in "Naming the Goddess"! Great perspective.:)', plus appearances at Stratford Literary Festival and the Tree House Bookshop, lecturing at Worcester University and being a tour guide in Stratford-upon-Avon, completing The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion and writing Shakespeare's Son ('The Life of Sir William Davenant'), and so on. But I didn't get round to it.

Instead, I'm going to preen myself a little over this, which my wife found online a day or two ago. Seems there's to be a rather interesting-looking course on the 'Renaissance of the Sacred Feminine', to be held at Avebury in Wiltshire (good location!) this coming August. Details can be found here.

If you click on the link and scroll down to the bottom section - 'Avebury/Wiltshire Reading List' - you'll see that the last entry concerns my King Arthur Conspiracy book. Alternatively, I'll save you the bother by copying what they wrote:

The King Arthur Conspiracy: How a Scottish prince became a mythical hero

By Simon Andrew Stirling

2012

First discovered during the Scotland adventure, this book is an indispensable read for anyone interested in the Arthur/Merlin/Avalon motif. All the latest research. It will expand your view beyond the emphasis on Glastonbury and Tintagel.

Now, seeing that made me feel really chuffed. It also made me want to get in touch with the organisers and tell them that, actually, all the latest research is probably best found in The Grail, due out in March, but that it was very kind of them to say those things about The King Arthur Conspiracy (and might help with a few book sales), and if there was anything I could do to contribute to their intriguing course in August they had only to ask.

Didn't get round to doing that, either. Although there's still time.

For the meantime, we're holding our breaths and crossing our fingers over the Beoley skull. With any luck, there'll be some scientific investigation of that particular item before too long. Maybe even a TV documentary. I'll keep you posted.

And my Davenant book is coming on apace. New discoveries about Shakespeare's relationship with Jane Davenant. All good clean fun. The manuscript's due to hit the editor's desk at the start of June.

There's another project in the wings, which I'll mention more about if things keep going smoothly. All in all, 2015 has a very exciting feel about it. I hope yours does, too.

TTFN!

It had occurred to me to write up a review of 2014 and the various things that happened last year - from publishing my first university paper on The Faces of Shakespeare to the publication, in September, of Naming the Goddess, in which I have an essay (tweet received this morning from Michigan: 'Loved your essay in "Naming the Goddess"! Great perspective.:)', plus appearances at Stratford Literary Festival and the Tree House Bookshop, lecturing at Worcester University and being a tour guide in Stratford-upon-Avon, completing The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion and writing Shakespeare's Son ('The Life of Sir William Davenant'), and so on. But I didn't get round to it.

Instead, I'm going to preen myself a little over this, which my wife found online a day or two ago. Seems there's to be a rather interesting-looking course on the 'Renaissance of the Sacred Feminine', to be held at Avebury in Wiltshire (good location!) this coming August. Details can be found here.

If you click on the link and scroll down to the bottom section - 'Avebury/Wiltshire Reading List' - you'll see that the last entry concerns my King Arthur Conspiracy book. Alternatively, I'll save you the bother by copying what they wrote:

The King Arthur Conspiracy: How a Scottish prince became a mythical hero

By Simon Andrew Stirling

2012

First discovered during the Scotland adventure, this book is an indispensable read for anyone interested in the Arthur/Merlin/Avalon motif. All the latest research. It will expand your view beyond the emphasis on Glastonbury and Tintagel.

Now, seeing that made me feel really chuffed. It also made me want to get in touch with the organisers and tell them that, actually, all the latest research is probably best found in The Grail, due out in March, but that it was very kind of them to say those things about The King Arthur Conspiracy (and might help with a few book sales), and if there was anything I could do to contribute to their intriguing course in August they had only to ask.

Didn't get round to doing that, either. Although there's still time.

For the meantime, we're holding our breaths and crossing our fingers over the Beoley skull. With any luck, there'll be some scientific investigation of that particular item before too long. Maybe even a TV documentary. I'll keep you posted.

And my Davenant book is coming on apace. New discoveries about Shakespeare's relationship with Jane Davenant. All good clean fun. The manuscript's due to hit the editor's desk at the start of June.

There's another project in the wings, which I'll mention more about if things keep going smoothly. All in all, 2015 has a very exciting feel about it. I hope yours does, too.

TTFN!

Monday, 1 December 2014

THE GRAIL ... Coming Soon!!!

A sneak preview, friends, of The Grail, coming soon from Moon Books.

Publication in March 2015.

Looking good, isn't it?

I've set up a Facebook page for the new book (click on "Facebook page" to go straight to it) and I'll keep you updated as the launch date draws nearer.

Meantime, work proceeds on Shakespeare's Son - my "Life of Sir William Davenant" - which has been keeping me pretty busy. And hoping to have some interesting news pretty soon regarding Shakespeare's skull.

Plenty more to come, folks!

Publication in March 2015.

Looking good, isn't it?

I've set up a Facebook page for the new book (click on "Facebook page" to go straight to it) and I'll keep you updated as the launch date draws nearer.

Meantime, work proceeds on Shakespeare's Son - my "Life of Sir William Davenant" - which has been keeping me pretty busy. And hoping to have some interesting news pretty soon regarding Shakespeare's skull.

Plenty more to come, folks!

Sunday, 2 November 2014

Pagan Pages

Just been told that an interview with me is now up on the PaganPages.org website.

So, with thanks to Mabh Savage, I give you ... The Pagan Pages Interview with Author Simon Stirling. I think it's a good one.

Toodle-pip!

So, with thanks to Mabh Savage, I give you ... The Pagan Pages Interview with Author Simon Stirling. I think it's a good one.

Toodle-pip!

Labels:

Arthur,

Artuir mac Aedain,

Beltane,

Grail,

Gunpowder Plot,

Halloween,

King Arthur Conspiracy,

Moon Books,

Muirgein,

Myrddin Wyllt,

Scotland,

The History Press,

Who Killed William Shakespeare

Monday, 18 August 2014

Naming the Goddess

Coming soon, from Moon Books - Naming the Goddess (Amazon.co.uk details here)

I contributed the chapter on "Christian Wisdom, Pagan Goddess: Reclaiming Sophia and the Saints from the Judeo-Christian Tradition".

Looking forward to reading the book as a whole!

I contributed the chapter on "Christian Wisdom, Pagan Goddess: Reclaiming Sophia and the Saints from the Judeo-Christian Tradition".

Looking forward to reading the book as a whole!

Sunday, 17 August 2014

Alyth, the Scene of Arthur's Last Battle

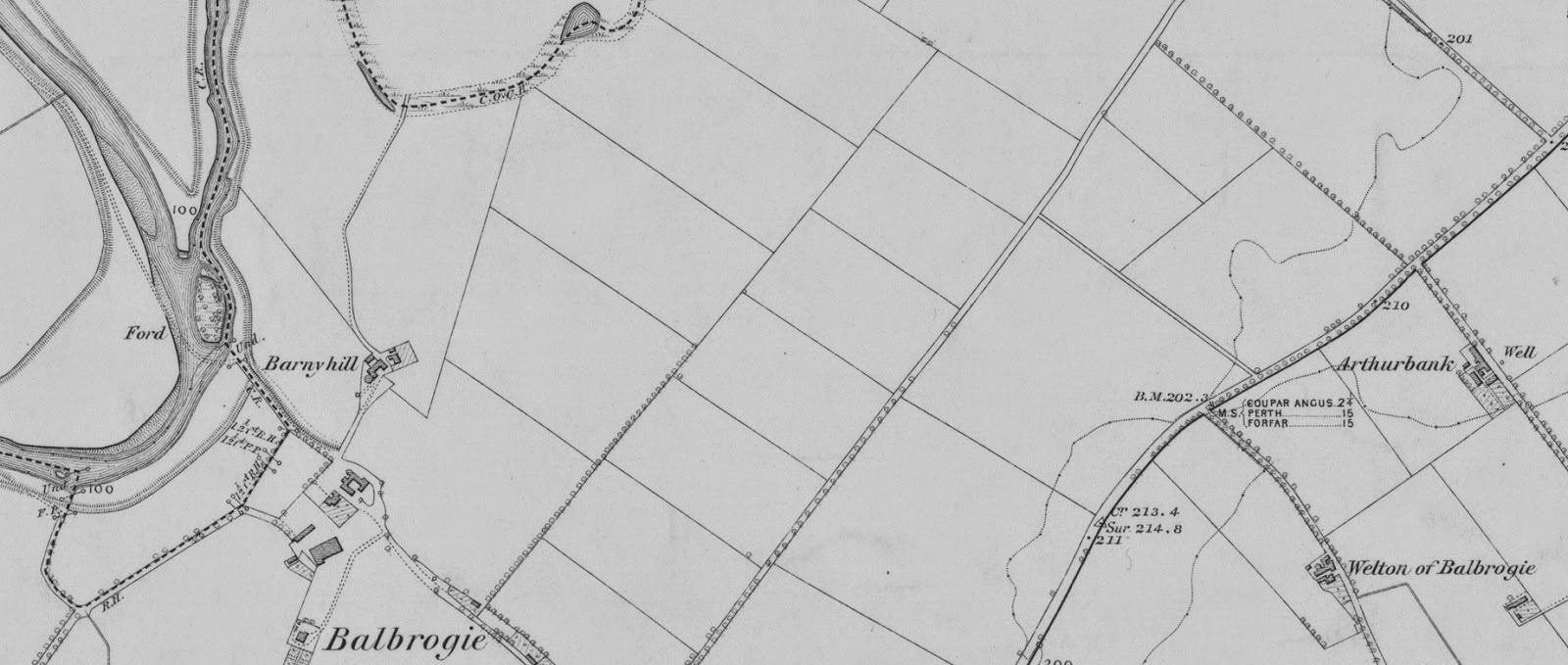

While I work on Shakespeare's Son - my biography of Sir William Davenant, a man of whom I'm becoming increasingly fond - The Grail continues to make its way through the publishing process, courtesy of Moon Books. So, by way of a sneak preview, in this post I shall offer up some of the evidence for the location of Arthur's last battle.

The Battle of Circenn

You probably think Arthur's last battle was fought at a place called "Camlann". I've been unable to find any reference to that place-name before the Middle Ages. The very earliest mentions of anyone called Arthur in the records indicate that he died in a battle fought in Angus, Scotland.

Adomnan of Iona's Life of Columba (circa 697) tells us that Artur son of Aedan was present when his father was "ordained" king of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574. The saint predicted the fates of Aedan's sons, announcing that Artur would "fall in battle, slain by enemies". Adomnan assured his readers that this prophecy came true when Artur and at least one of his brothers was killed in a "battle of the Miathi".

The Miathi, or Maeatae, were a Pictish tribe: essentially, they held the low-lying lands to the south and east of the Highland massif. Another Latinate term for these people was Verturiones.

The Irish annals, which drew at least some of their information from the records kept by Columba's monks on the Isle of Iona, specify that Artur son of Aedan died in a "battle of Circenn". This refers to the Pictish province which was roughly contiguous with today's Angus and the Mearns. The term Circenn combined the Gaelic cir, meaning a "comb" or "crest", and cenn, "heads". Circenn, then, was the land of the Comb-heads. This tells us that the Miathi Picts modelled their appearance on their totem beast, the boar (rather like their compatriots in the Orkneys, the Orcoi, from orc - a young boar). Indeed, it is possible that the Latinate name for the Verturiones tribe combines verres and turio and indicates the "offshoots" or "offspring" of the "boar", while the very term "Pict" (variant, "Pecti", "Pecht") quite possibly derived from the Latin pecten, a "comb".

Now, let's look at "Camlann" - the traditional name for Arthur's last battle. Its first appearance in the records comes in an entry interpolated into the Welsh Annals, where it refers to a gueith cam lann or "strife of cam lann". By the time this came to be written down, the region in which Artur son of Aedan died was speaking a version of Northumbrian Old English which became the dialect known as Lowland Scots. In that dialect, cam lann would mean "comb land".

In other words, "Camlann" is merely an anglicised version of the Gaelic Circenn, the land of the "Comb-heads" in which the first Arthur on record fell in a cataclysmic battle.

Culhwch and Olwen

One of the oldest of the Welsh (i.e. British) tales to feature Arthur is that of Culhwch ac Olwen. It forms a sort of mythologised, potted account of Arthur's career, culminating in the desperate and bloody hunt for a king who - for his sins - was turned into a boar. This hunt begins with a violent amphibious landing, at a site which can be identified as Cruden Bay, on the Aberdeenshire coast, after which Arthur is met by the "saints of Ireland" who "besought his protection". The dreadful Boar-King is challenged and chased from Esgeir Oerfel, the "Cold Ridge" of the Grampians, the Boar-King making his way across country towards Llwch Tawy (Loch Tay) before he is intercepted by Arthur and his men and driven into a river.

In The King Arthur Conspiracy I identified the treacherous Boar-King as Morgan the Wealthy, a renegade British prince who abducted Arthur's wife, Gwenhwyfar, and escaped into the land of the Miathi Picts (his bolt hole appears to have been the fortified Hill of Tillymorgan in Strathbogie). The site where Morgan finally came to grief is marked by the "Morganstone" on the west bank of the River Ericht, a short distance to the west of the Hill of Alyth in the great vale of Strathmore in Angus.

Arthurian Connections with Alyth

Before we proceed, let us consider some ancient references to Arthur and his family in the context of Alyth and its immediate vicinity.

In addition to having a son named Artur or Artuir, King Aedan of the Scots had a daughter called Muirgein. According to Whitley Stokes, editing and translating the Martyrology of a 9th-century Irish monk called Oengus, Muirgein daughter of Aedan was born "in Bealach Gabrain".

The inability of certain scholars to find a "Bealach Gabrain" in Scotland has led some to argue that Muirgein daughter of Aedan was utterly unconnected with Artur son of Aedan. But place-names evolve. The Gaelic term bealach, meaning a "pass" or "gorge", usually appears as "Balloch" on today's maps. There is a "Balloch" which runs along the feet of Barry Hill and the adjacent Hill of Alyth in Strathmore.

Furthermore, this "Balloch" or bealach was in a region named after the grandfather of Artur and Muirgein. Gabran was the father of Aedan. He ruled the Scots for twenty years until his death in about AD 559 and gave his name to the region of Gowrie (a corruption of Gabran). The "Balloch" near Alyth was in Gabran's land (Gabrain) and lies close to the town of Blairgowrie, which also recalls the name of Arthur's grandfather. The "Balloch" at the foot of the Hill of Alyth was almost certainly the "Bealach Gabrain" or "pass of Gowrie" where Arthur's (half-)sister, Muirgein daughter of Aedan mac Gabrain, was born. To pretend that the Balloch of Gowrie could not have been "Bealach Gabrain" because they are not spelled the same way these days is tantamount to claiming that Londinium and London could not have been the same place.

So Arthur's sister, Muirgein (latterly, Morgan le Fay), was born near Alyth. Writing in about 1527, the Scottish historian Hector Boece also indicated that Arthur's wife was buried at Meigle, which is just a mile or two south of Alyth. Hector Boece's local tradition recalled Gwenhwyfar as Vanora (via Guanora) and claimed that she had been held hostage in the Iron Age hill-fort atop Barry Hill, adjacent to the Hill of Alyth, before she was executed and buried in what is now the kirkyard at Meigle. A carved Pictish standing stone, now on display at the Meigle museum, reputedly depicts the execution or burial of Arthur's wife.

Y Gododdin

One of the best sources of information about Arthur's last battle is the ancient epic, Y Gododdin. This was composed and sung by Aneirin, a British bard of the Old North, and can be dated to circa AD 600 (the date of Arthur's last battle is given in the Irish annals as, variously, AD 594 and 596).

Unfortunately, the relevance of Aneirin's elegiac tribute to the warriors of Lothian (the "Gododdin") has been missed by scholars who want to believe that the poem bemoans the destruction of a British war-band from the Edinburgh area which had the misfortune to be wiped out at a mythical battle fought at Catterick in North Yorkshire. No evidence exists that any such battle was fought. The Angles (forerunners of the English) preferred not to recollect their defeats but were happy to remember, and to boast about, their victories. If the Angles of Northumbria had indeed obliterated a British band of heroes from Lothian at Catterick, we might assume that they would have remembered doing so. And no scholar has yet explained the presence of "Irishman and Picts" at this imaginary battle in Anglian territory.

A verse or two of Y G[ododdin, added at a later date than the original composition, described a battle fought in Scotland (Strathcarron) in AD 642 and the death in that battle of a Scottish king who just happened to be a nephew of Artur son of Aedan. This interpolation does at least suggest that the subject of the original poem was a battle fought in roughly the same area (Scotland) by the family of Artur and his father Aedan. The Y Gododdin poem also mentions various famous warriors who appear in the early accounts of Arthur's career and who were contemporary with Artur son of Aedan.

One surviving version of Y Gododdin even mentions Artur/Artuir by name:

Gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef Arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

Confused by the misidentification of the battle sung about by Aneirin in Y Gododdin, and the assumption that Arthur himself could not have been present at that battle, scholars have persistently mistranslated this verse - mostly in an attempt to render the second half of the second line, "He was no Arthur". But Aneirin's verse should properly be translated thus:

Black ravens [warriors] sang in praise of the hero [Welsh, arwr]

of Circenn [transliterated into Welsh as "caer ceni"]. He blamed Arthur;

the dogs cursed in return for our wailing/lamentation ...

Aneirin indicated, in his Y Gododdin elegy, precisely where the final battle took place:

Eil with gwelydeint amallet

y gat veirch ae seirch greulet

bit en anysgoget bit get ...

Which translates as:

Again they came into view around the alled,

the battle-horses and the bloody armour,

still steadfast, still united ...

The "alled" was Aneirin's Welsh-language attempt at the Gaelic Allaid - also Ailt - or the Hill of Alyth.

Breuddwyd Rhonabwy

The extraordinary medieval Welsh tale of The Dream of Rhonabwy actually provides a description of the scene in the hours before Arthur's last battle was fought. The visionary seer, Rhonabwy, finds himself crossing a great plain with a river running through it (Strathmore). He is met by a character call Iddog, "Churn of Britain", who admits that it was he who caused the cataclysmic "battle of Camlan" by betraying Arthur. In company with Iddog, Rhonabwy approaches the "Ford of the Cross" (Rhyd-y-Groes) on the river. A great army is encamped on either side of the road and Arthur is seated on a little flat islet in the river, beside the ford.

The topography precisely matches the detail from a 19th-century Ordnance Survey map of the area around Alyth seen at the top of this post. On the right-hand side of the detail is the ridge known as Arthurbank, which lies along the River Isla, opposite the junction of the River Ericht with the River Isla (a few miles down the Ericht from the site of the Morganstone). A little flat islet lies in the River Isla, close to the Arthurbank shore, and a ford runs alongside this little islet, exactly as described in the Welsh account of Rhonabwy's dream.

Aneirin also mentioned this ford in his Y Gododdin poem as rhyd benclwyd - the "ford" of the "grey" or "holy mount". There is, indeed, a Greymount marked on the map, a short distance to the north of the ford on the Isla. In his Agriculture of Perthshire, published in 1799, the Rev. Dr Robertson described the discovery of a "large Druidical temple" at Coupar Grange, adjacent to this ford. A standing stone found in this "temple" would no doubt have been rebranded a "cross" by the early Christians, so that the ford across the Isla, beside the little flat islet, would have become known as the Ford of the Cross (Rhyd-y-Groes), as described in The Dream of Rhonabwy, or the "Ford of the Grey/Holy Mount" (rhyd benclwyd) as described by Aneirin.

Until the late 18th century, an Arthurstone stood at the south-eastern edge of the Arthurbank ridge (its presence is still marked on the map). This Arthurstone corresponds to the Morganstone, a few miles away up the River Ericht, and marks the spot where Arthur fell in his battle with the Boar-King of the Miathi Picts in the land of the "crested" Comb-heads, Camlann.

The Head of the Valley of Sorrow

After the battle, Arthur's wife Gwenhwyfar was executed and buried only a mile or so away at Meigle. The legend of Culhwch and Olwen (which, interestingly, features a treacherous individual identified as Grugyn, who also appears in Aneirin's Y Gododdin) tells us that, after the battle at the river with the dangerous Boar-King, Arthur and his heroes once more "set out for the North" to overcome a fearsome witch. She was found inside a cave at Penn Nant Gofid - the "Head of the Valley of Sorrow"- on "the confines of Hell" (which we can interpret as the edge of the territory controlled by those boar-like Miathi Picts). The Welsh gofid ("sorrow/trouble/affiction/grief") appears to have been something of a pun, for another Welsh word for sorrow or grief is alaeth (compare Ailt, Allaid and Alyth, the "Head of the Valley of Alyth" being the very hill on which Arthur's wife is rumoured to have been held prisoner before her execution and burial nearby at Meigle).

In the Welsh tale, this witch is known as Orddu (that is, Gorddu - "Very Black"). A similar legend from the Isle of Mull, whose Arthurian associations have been overlooked for far too long, names the troublesome wife as Corr-dhu ("Black-Crane").

We might also note that the 9th-century Welsh monk known as Nennius described a "wonder" of Scotland in the form of "a valley in Angus, in which shouting is heard every Monday night; Glend Ailbe is its name, and it is not known who makes this noise."

Nennius's Glend Ailbe seems to be a corruption of the Gaelic word for a valley (glen) and the River Isla, or perhaps the Allaid or Hill of Alyth, which dominates the vale of Strathmore. The mysterious shouting in this "Valley of Sorrow" was reputedly heard ever Monday night. And we know from Aneirin's eye-witness account of Arthur's last battle that it came to an end on a Monday.

This is just some of the evidence for Arthur having fallen in the vicinity of Alyth. There is plenty more to come in The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - including descriptions of the Pictish symbol stones, found close to the site of that battle, which actually depict the Grail in use!

I'll let you know when the book is about to be published.

Monday, 28 July 2014

Apologia

I've been remiss. Dreadfully so.

The only thing I can say in my defence is that I have been busy writing my biography of Sir William Davenant (Shakespeare's Son) and enjoying myself giving tours in Stratford-upon-Avon - some days, you might see me in doublet and breeches, leading a troupe of tourists or students from one Shakespearean site to another, whilst on Saturday evenings I guide intrepid visitors through the dark delights of Tudor World on Sheep Street, every Ghost Tour threatening to yield at least one supernatural experience. So, yes, I've been busy.

Added to that, my paper on The Faces of Shakespeare is about to be published by Goldsmiths University; Moon Books will soon be publishing Naming the Goddess, to which I contributed a chapter, and my own The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion is currently passing through the Moon Books production process. Oh, and I've also been quietly working on a project based on events in 1964-65 for a company set up by a very good friend of mine from my drama school days.

So I hope you'll forgive the radio silence.

Anyhoo - my great buddy and artistic collaborator on The Grail, Lloyd Canning, got a fantastic four-page spread in this month's Cotswold and Vale Magazine, including (as you can see) the cover shot. Lloyd's amazing images really came out well in the magazine, and The Grail got a good mention (as well as my Who Killed William Shakespeare?), which means that we're all very chuffed. A hearty CONGRATS to Lloyd for the well-earned and much-deserved publicity.

I'll try to post another update very soon. I promise.

The only thing I can say in my defence is that I have been busy writing my biography of Sir William Davenant (Shakespeare's Son) and enjoying myself giving tours in Stratford-upon-Avon - some days, you might see me in doublet and breeches, leading a troupe of tourists or students from one Shakespearean site to another, whilst on Saturday evenings I guide intrepid visitors through the dark delights of Tudor World on Sheep Street, every Ghost Tour threatening to yield at least one supernatural experience. So, yes, I've been busy.

Added to that, my paper on The Faces of Shakespeare is about to be published by Goldsmiths University; Moon Books will soon be publishing Naming the Goddess, to which I contributed a chapter, and my own The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion is currently passing through the Moon Books production process. Oh, and I've also been quietly working on a project based on events in 1964-65 for a company set up by a very good friend of mine from my drama school days.

So I hope you'll forgive the radio silence.

Anyhoo - my great buddy and artistic collaborator on The Grail, Lloyd Canning, got a fantastic four-page spread in this month's Cotswold and Vale Magazine, including (as you can see) the cover shot. Lloyd's amazing images really came out well in the magazine, and The Grail got a good mention (as well as my Who Killed William Shakespeare?), which means that we're all very chuffed. A hearty CONGRATS to Lloyd for the well-earned and much-deserved publicity.

I'll try to post another update very soon. I promise.

Monday, 2 June 2014

The Meaning of "Camlann"

I received a message from Moon Books today, telling me that the copyedited manuscript of The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion is ready for me to check.

It seems unlikely that the book will be available before the Scottish independence referendum in September. I'll be keeping a close eye on the referendum: the vote takes place the day before my 12th wedding anniversary, and having got married on the Isle of Iona to a woman who is half-Scottish, as well as having gone to university in Glasgow, my sympathies lie very much with the "YES" campaign.

I was also interested to note that Le Monde published this piece, indicating that the pro-independence campaign is gaining ground. The reporter had been in Alyth, Perthshire, to follow the debate. Alyth, as I revealed in The King Arthur Conspiracy, is where Arthur fought his last battle.

How do I know this? Lots of reasons, not least of all the fact that the place is name checked in a contemporary poem of the battle.

But wasn't Arthur's last battle fought at a place called Camlan?

Well, for a long while I wasn't so sure. Now, though, I know that it was - sort of - and I explain why in my forthcoming book on The Grail. But as that may not be out before the referendum, I hereby present this information as a gift to the "YES" campaign and in honour of a warrior who gave his life fighting for Scottish (and British) independence.

Many commentators refuse to accept that the place-name "Camlan" isn't Welsh. The fact that Camlan is the Gaelic name for the old Roman fortifications at Camelon, near Falkirk in central Scotland, means nothing to them. Arthur's "Camlan" was Welsh, and that's all it could have been.

Very silly - and utterly useless, in terms of trying to track down the site of that all-important battle. If it was a Welsh place-name, it would have meant something like "Crooked Valley", which really doesn't help us very much.

The first literary reference to "Camlann" comes in the Annales Cambriae ("Welsh Annals") which mention Gueith cam lann - the "Strife of Camlann". However, that reference cannot be traced back to an earlier date than the 10th century, hundreds of years after the time of Arthur. The contemporary sources make no mention of "Camlann", and so it may be that the name didn't come into use until many years after Arthur's last battle was fought there.

The earliest literary reference to anyone called Arthur concerns an individual named Artur mac Aedain. He was a son of Aedan mac Gabrain, who was "ordained" King of the Scots by St Columba in 574. Accounts of the ordination ceremony indicate that Arthur son of Aedan was present on that occasion, and that St Columba predicted that Arthur would not succeed his father to the Scottish throne but would "fall in battle, slain by enemies."

Those same accounts tell us that Columba's prophecy came true: Artur mac Aedain died in a "battle of the Miathi", which means that he was killed fighting the Picts of central Scotland.

The Irish Annals, which were compiled from notes made by the monks of Iona, inform us that the first recorded Arthur was killed in a "battle of Circenn", fought in about 594. Circenn was the Pictish province immediately to the north of the Tay estuary - broadly, Angus and the Mearns - which was indeed the territory of the "Miathi".

Circenn might have been Pictish territory, but the name of the province is Gaelic. It combines the word cir (meaning a "comb" or a "crest") and cenn, the genitive plural of a Gaelic noun meaning "head". An appropriate translation of Circenn would therefore be "Comb-heads".

The Miathi Picts, like their compatriots in the Orkneys, appear to have modelled their appearance on their totem animal, the boar. This meant that they shaved their heads in imitation of the boar's comb or crest - rather like the Mohawk tonsure, which we wrongly think of as a "Mohican". Indeed, whilst we assume that the term "Pict" derived from the Latin picti, meaning "painted" or "tattooed", there are grounds for suspecting that it was actually a corruption of pecten, the Latin for a "comb" (hence the Old Scots word Pecht, meaning "Pict").

So where does "Camlann" fit into all this?

After Arthur's death, much of southern and central Scotland was invaded by the Angles, those forerunners of the English. As a consequence, the Germanic language known as Northumbrian Old English was established in southern and central Scotland by the 7th century. It eventually became the dialect called Lowland Scots.

In the Scots dialect, came, kem and camb all meant "comb". And lan', laan and lann all meant "land".

The land in which Arthur's last battle had been fought - that is, the Pictish province of Angus - was soon speaking an early variant of the English language, or Lowland Scots. The fact that the Pictish province of Circenn was named after its "Comb-heads", those Miathi warriors who cut their hair to resemble a boar's comb or crest, meant that the place became known by its early English equivalent: "Comb-land" or Camlann.

This was not, of course, the name that Arthur and his warrior-poets would have used for the place. But then, the term "Camlann" didn't appear in any literary source for at least another three or four hundred years. By the time the Welsh annalist came to interpolate the "Camlann" entry into the Annales Cambriae, the location had become known by its Old English/Lowland Scots name. But that name was merely a variant of the older Gaelic name for the province - Circenn, or "Comb-heads".

And that is where the first recorded Arthur fell in battle, as St Columba had predicted. Not in England or Wales or Brittany, but in Angus in Scotland.

The province of the Pictish "Comb-heads". The region known as "Comb-land", cam lann.

It seems unlikely that the book will be available before the Scottish independence referendum in September. I'll be keeping a close eye on the referendum: the vote takes place the day before my 12th wedding anniversary, and having got married on the Isle of Iona to a woman who is half-Scottish, as well as having gone to university in Glasgow, my sympathies lie very much with the "YES" campaign.

I was also interested to note that Le Monde published this piece, indicating that the pro-independence campaign is gaining ground. The reporter had been in Alyth, Perthshire, to follow the debate. Alyth, as I revealed in The King Arthur Conspiracy, is where Arthur fought his last battle.

How do I know this? Lots of reasons, not least of all the fact that the place is name checked in a contemporary poem of the battle.

But wasn't Arthur's last battle fought at a place called Camlan?

Well, for a long while I wasn't so sure. Now, though, I know that it was - sort of - and I explain why in my forthcoming book on The Grail. But as that may not be out before the referendum, I hereby present this information as a gift to the "YES" campaign and in honour of a warrior who gave his life fighting for Scottish (and British) independence.

Many commentators refuse to accept that the place-name "Camlan" isn't Welsh. The fact that Camlan is the Gaelic name for the old Roman fortifications at Camelon, near Falkirk in central Scotland, means nothing to them. Arthur's "Camlan" was Welsh, and that's all it could have been.

Very silly - and utterly useless, in terms of trying to track down the site of that all-important battle. If it was a Welsh place-name, it would have meant something like "Crooked Valley", which really doesn't help us very much.

The first literary reference to "Camlann" comes in the Annales Cambriae ("Welsh Annals") which mention Gueith cam lann - the "Strife of Camlann". However, that reference cannot be traced back to an earlier date than the 10th century, hundreds of years after the time of Arthur. The contemporary sources make no mention of "Camlann", and so it may be that the name didn't come into use until many years after Arthur's last battle was fought there.

The earliest literary reference to anyone called Arthur concerns an individual named Artur mac Aedain. He was a son of Aedan mac Gabrain, who was "ordained" King of the Scots by St Columba in 574. Accounts of the ordination ceremony indicate that Arthur son of Aedan was present on that occasion, and that St Columba predicted that Arthur would not succeed his father to the Scottish throne but would "fall in battle, slain by enemies."

Those same accounts tell us that Columba's prophecy came true: Artur mac Aedain died in a "battle of the Miathi", which means that he was killed fighting the Picts of central Scotland.

The Irish Annals, which were compiled from notes made by the monks of Iona, inform us that the first recorded Arthur was killed in a "battle of Circenn", fought in about 594. Circenn was the Pictish province immediately to the north of the Tay estuary - broadly, Angus and the Mearns - which was indeed the territory of the "Miathi".

Circenn might have been Pictish territory, but the name of the province is Gaelic. It combines the word cir (meaning a "comb" or a "crest") and cenn, the genitive plural of a Gaelic noun meaning "head". An appropriate translation of Circenn would therefore be "Comb-heads".

The Miathi Picts, like their compatriots in the Orkneys, appear to have modelled their appearance on their totem animal, the boar. This meant that they shaved their heads in imitation of the boar's comb or crest - rather like the Mohawk tonsure, which we wrongly think of as a "Mohican". Indeed, whilst we assume that the term "Pict" derived from the Latin picti, meaning "painted" or "tattooed", there are grounds for suspecting that it was actually a corruption of pecten, the Latin for a "comb" (hence the Old Scots word Pecht, meaning "Pict").

So where does "Camlann" fit into all this?

After Arthur's death, much of southern and central Scotland was invaded by the Angles, those forerunners of the English. As a consequence, the Germanic language known as Northumbrian Old English was established in southern and central Scotland by the 7th century. It eventually became the dialect called Lowland Scots.

In the Scots dialect, came, kem and camb all meant "comb". And lan', laan and lann all meant "land".

The land in which Arthur's last battle had been fought - that is, the Pictish province of Angus - was soon speaking an early variant of the English language, or Lowland Scots. The fact that the Pictish province of Circenn was named after its "Comb-heads", those Miathi warriors who cut their hair to resemble a boar's comb or crest, meant that the place became known by its early English equivalent: "Comb-land" or Camlann.

This was not, of course, the name that Arthur and his warrior-poets would have used for the place. But then, the term "Camlann" didn't appear in any literary source for at least another three or four hundred years. By the time the Welsh annalist came to interpolate the "Camlann" entry into the Annales Cambriae, the location had become known by its Old English/Lowland Scots name. But that name was merely a variant of the older Gaelic name for the province - Circenn, or "Comb-heads".

And that is where the first recorded Arthur fell in battle, as St Columba had predicted. Not in England or Wales or Brittany, but in Angus in Scotland.

The province of the Pictish "Comb-heads". The region known as "Comb-land", cam lann.

Monday, 17 March 2014

My Writing Process (blog tour)

I was "tagged" to take part in this blog hop by the wonderful Margaret Skea, whom I have known since the Authonomy days, and who posted about her writing process on her own blog last week.

Margaret passed on to me the four questions that writers are invited to answer as part of this blog tour.

So, here goes ...

1. What am I working on?

Right now, I'm finishing one project and starting another. The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Tradition has been occupying my time now since January 2013. I was looking to do something of a follow up to The King Arthur Conspiracy, partly because I had been doing some more research - especially into the location and circumstances of Arthur's last battle - and partly because I wanted to address some of the (very minor) objections to Artuir mac Aedain having been the original Arthur of legend.

Thanks to Trevor Greenfield of Moon Books, I was given the opportunity to write The Grail in an unusual way. Each month, from January to December 2013, I would write a chapter, which would then by uploaded onto the Moon Books blog. That meant that, each month, I would send my draft chapter to my associate, John Gist, in New Mexico, who would read it and comment on it for me, and I would visit my friend Lloyd Canning, a local up-and-coming artist, to discuss the illustration that would accompany the chapter. There would be a final rewrite, and then I'd submit the chapter and the image to Trevor at Moon Books.

It was a long process, and an odd one (I wouldn't normally submit anything less than a complete manuscript). I've spent the last couple of months revising the full text and adding a few more illustrations. And, well, it's about finished. John contacted me from the States last night to say that he had read through one of the more recent drafts of the full thing and he really liked it. It's not all about the distant past - there's a lot about how our brains work, and how a certain type of mind tends to ruin history (and other things) for everybody else. That type of mindset seeks to prevent research into figures like Artuir mac Aedain so that the prevailing myth can be maintained. The same type of mindset will cause us no end of problems in the immediate future, and the book ends with something of a prediction.

Coming up ... Sir William Davenant. I published a piece on The History Vault, a couple of days ago, about Shakespeare's Dark Lady. It could be read as a sort of introduction to my biography of Sir William Davenant. I've only just signed the contract for the Davenant book, and it's due to be handed in to The History Press in June 2015.

2. How does my work differ from others of its genre?

History for me is an investigative process. I lose patience very quickly with historians who do nothing more than repeat what the last historian said. It's a major problem: a consensus arises, and woe betide any self-respecting historian who challenges that consensus. But the consensus is often based, not on historical facts, but on a kind of political outlook. It tends to be history-as-we-would-like-it-to-be, rather than history-as-it-was.

There are similarities with archaeology. Dig down anywhere within the Roman walls of the old city of London and you'll hit a layer of dark earth. This was left behind by Boudica when she and her Iceni warriors destroyed Londinium in about AD 60. But if you don't dig down far enough, you won't find that layer.

Too much history - certainly where Arthur (and the Grail) and Shakespeare (and Davenant) are concerned - gets down as far as one layer and stays there. In the case of Arthur, that layer is the 12th century; with Shakespeare, it's the late 18th century. In both instances, that's when the story changed. New versions of Arthur and Shakespeare arose, reflecting the obsessions of the particular era. When historians dig down to that layer, and report on what they've found, they're not writing about Arthur or Shakespeare - they're writing about what later generations wanted to think about Arthur and Shakespeare.

You have to go down further. Otherwise, you're just repeating propaganda.

I'm also a bit fussy about how my books read. That's my dramatist background, I reckon. But I read a great many books - history, mostly, of course - and too many of them are, frankly, boring. I seek to write exciting, accessible history that has been more diligently researched than the norm. I don't seek to shock, but real history often is shocking. Maybe that's why so many historians prefer to keep telling the "consensus" story.

3. Why do I write what I do?

The work I do now started because I was intrigued and inquisitive. The familiar legends of Arthur are all well and good, but I was more interested in the man who inspired them - who was he? what made him so special? And the same with Shakespeare - how did a Warwickshire lad become the greatest writer in the English language? (My own background is not too different from Shakespeare's.) And what was the inspiration for the character of Lady Macbeth.

I'm still intrigued and inquisitive, but over the years I've found myself more and more determined to see justice done - to right the wrongs of the past. Those wrongs are perpetuated by historians who don't ask questions. And that's a betrayal, not only of the actual subjects (Arthur, Shakespeare) but also of the reader today. It's a kind of cover-up, designed - I believe - to reshape the past so that it justifies certain policies today. If you're a monarchist, for example, or an old-fashioned imperialist, you're going to want to believe that Queen Elizabeth I was marvellous. And then you're going to have to believe that Shakespeare thought she was marvellous. Which means that you'll have to turn a blind eye to what was going on during her reign, and to the criticisms which Shakespeare voiced. Before you know it, you're ignoring the facts altogether in order to write a history that supports your own prejudices. I can't believe how often that happens.

Both Arthur and Shakespeare were killed, and their stories were subsequently written up by their enemies. Their real stories are much more interesting - and they deserve to be told. If we cling to the myths, we allow demagogues to dictate our history to us.

4. How does my writing process work?

Well, it's not quick. The research can take years. Then there are usually a number of false starts. Fortunately, I tend to have some sort of agreement with a publisher, these days, so when I say I'm going to write something, that means I have to get on with it.

I'll start at the beginning, with the long, slow process of getting words down on the page (it's long and slow because I have to go hunting for the information before I put it down). But I always have a carefully worked out structure in my mind, and day after day a kind of rough draft takes shape. It's usually fairly messy, and at some point I'll stop and go back to the start, smartening it up and giving myself enough momentum to plough on and get a few more chapters drafted.

After that, it's an ongoing process of revision (never less than three drafts). For several months, I'll be revising the early chapters while I'm still drafting the later ones.

I have to work pretty much every day. For a finished manuscript of, say, 100,000 words, I'll expect to write anything up to 500,000 words, which will be sifted and boiled down to fit the appropriate length. I'll keep going back and revising different sections, here and there, and often, in the latter stages, I'll rewrite the chapters out of sequence (partly to keep them all fresh). Then there's endless, obsessive tinkering, as I fuss over every full stop and comma.

The King Arthur Conspiracy took seven months to write (and rewrite). Who Killed William Shakespeare? took nine months, and then some for the illustrations. The Grail took me a year to write (a chapter a month) and another 2-3 months to revise (with illustrations). With Sir William Davenant I want to create something special, so that'll take ages.

There are two things I couldn't do without. One is coffee. The other is my fantastically loyal, supportive and organised wife, Kim.

*****

I now get to tag a couple of authors who will pick up the baton and run with it, and I've chosen two great writers who are part of the Review Group on Facebook. I'll let the first introduce herself:

I’m Louise Rule, my first book Future Confronted was published in December 2013, and I am now researching my next book, the story of which will take me travelling from Scotland to England, and then to Italy. I am on the Admin Team of the Facebook group The Review Blog which I enjoy immensely.

Louise's blog can be found here.

My other chosen successor on this blog tour is Stuart S. Laing. Stuart writes about Scottish history - his posts on the Review Group Blog covering fascinating moments in Edinburgh's past are a joy to read, but it's his historical novels - the Robert Young of Newbiggin Mysteries - which really deserve attention.

Stuart's blog can be found here.

Finally, it remains for me only to thank Margaret Skea for inviting me to take part in this hop. And to thank you, dear reader, for perusing my musings.

Ciao!

Margaret passed on to me the four questions that writers are invited to answer as part of this blog tour.

So, here goes ...

1. What am I working on?

Right now, I'm finishing one project and starting another. The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Tradition has been occupying my time now since January 2013. I was looking to do something of a follow up to The King Arthur Conspiracy, partly because I had been doing some more research - especially into the location and circumstances of Arthur's last battle - and partly because I wanted to address some of the (very minor) objections to Artuir mac Aedain having been the original Arthur of legend.

Thanks to Trevor Greenfield of Moon Books, I was given the opportunity to write The Grail in an unusual way. Each month, from January to December 2013, I would write a chapter, which would then by uploaded onto the Moon Books blog. That meant that, each month, I would send my draft chapter to my associate, John Gist, in New Mexico, who would read it and comment on it for me, and I would visit my friend Lloyd Canning, a local up-and-coming artist, to discuss the illustration that would accompany the chapter. There would be a final rewrite, and then I'd submit the chapter and the image to Trevor at Moon Books.

It was a long process, and an odd one (I wouldn't normally submit anything less than a complete manuscript). I've spent the last couple of months revising the full text and adding a few more illustrations. And, well, it's about finished. John contacted me from the States last night to say that he had read through one of the more recent drafts of the full thing and he really liked it. It's not all about the distant past - there's a lot about how our brains work, and how a certain type of mind tends to ruin history (and other things) for everybody else. That type of mindset seeks to prevent research into figures like Artuir mac Aedain so that the prevailing myth can be maintained. The same type of mindset will cause us no end of problems in the immediate future, and the book ends with something of a prediction.

Coming up ... Sir William Davenant. I published a piece on The History Vault, a couple of days ago, about Shakespeare's Dark Lady. It could be read as a sort of introduction to my biography of Sir William Davenant. I've only just signed the contract for the Davenant book, and it's due to be handed in to The History Press in June 2015.

2. How does my work differ from others of its genre?

History for me is an investigative process. I lose patience very quickly with historians who do nothing more than repeat what the last historian said. It's a major problem: a consensus arises, and woe betide any self-respecting historian who challenges that consensus. But the consensus is often based, not on historical facts, but on a kind of political outlook. It tends to be history-as-we-would-like-it-to-be, rather than history-as-it-was.

There are similarities with archaeology. Dig down anywhere within the Roman walls of the old city of London and you'll hit a layer of dark earth. This was left behind by Boudica when she and her Iceni warriors destroyed Londinium in about AD 60. But if you don't dig down far enough, you won't find that layer.

Too much history - certainly where Arthur (and the Grail) and Shakespeare (and Davenant) are concerned - gets down as far as one layer and stays there. In the case of Arthur, that layer is the 12th century; with Shakespeare, it's the late 18th century. In both instances, that's when the story changed. New versions of Arthur and Shakespeare arose, reflecting the obsessions of the particular era. When historians dig down to that layer, and report on what they've found, they're not writing about Arthur or Shakespeare - they're writing about what later generations wanted to think about Arthur and Shakespeare.

You have to go down further. Otherwise, you're just repeating propaganda.

I'm also a bit fussy about how my books read. That's my dramatist background, I reckon. But I read a great many books - history, mostly, of course - and too many of them are, frankly, boring. I seek to write exciting, accessible history that has been more diligently researched than the norm. I don't seek to shock, but real history often is shocking. Maybe that's why so many historians prefer to keep telling the "consensus" story.

3. Why do I write what I do?

The work I do now started because I was intrigued and inquisitive. The familiar legends of Arthur are all well and good, but I was more interested in the man who inspired them - who was he? what made him so special? And the same with Shakespeare - how did a Warwickshire lad become the greatest writer in the English language? (My own background is not too different from Shakespeare's.) And what was the inspiration for the character of Lady Macbeth.

I'm still intrigued and inquisitive, but over the years I've found myself more and more determined to see justice done - to right the wrongs of the past. Those wrongs are perpetuated by historians who don't ask questions. And that's a betrayal, not only of the actual subjects (Arthur, Shakespeare) but also of the reader today. It's a kind of cover-up, designed - I believe - to reshape the past so that it justifies certain policies today. If you're a monarchist, for example, or an old-fashioned imperialist, you're going to want to believe that Queen Elizabeth I was marvellous. And then you're going to have to believe that Shakespeare thought she was marvellous. Which means that you'll have to turn a blind eye to what was going on during her reign, and to the criticisms which Shakespeare voiced. Before you know it, you're ignoring the facts altogether in order to write a history that supports your own prejudices. I can't believe how often that happens.

Both Arthur and Shakespeare were killed, and their stories were subsequently written up by their enemies. Their real stories are much more interesting - and they deserve to be told. If we cling to the myths, we allow demagogues to dictate our history to us.

4. How does my writing process work?

Well, it's not quick. The research can take years. Then there are usually a number of false starts. Fortunately, I tend to have some sort of agreement with a publisher, these days, so when I say I'm going to write something, that means I have to get on with it.

I'll start at the beginning, with the long, slow process of getting words down on the page (it's long and slow because I have to go hunting for the information before I put it down). But I always have a carefully worked out structure in my mind, and day after day a kind of rough draft takes shape. It's usually fairly messy, and at some point I'll stop and go back to the start, smartening it up and giving myself enough momentum to plough on and get a few more chapters drafted.

After that, it's an ongoing process of revision (never less than three drafts). For several months, I'll be revising the early chapters while I'm still drafting the later ones.

I have to work pretty much every day. For a finished manuscript of, say, 100,000 words, I'll expect to write anything up to 500,000 words, which will be sifted and boiled down to fit the appropriate length. I'll keep going back and revising different sections, here and there, and often, in the latter stages, I'll rewrite the chapters out of sequence (partly to keep them all fresh). Then there's endless, obsessive tinkering, as I fuss over every full stop and comma.

The King Arthur Conspiracy took seven months to write (and rewrite). Who Killed William Shakespeare? took nine months, and then some for the illustrations. The Grail took me a year to write (a chapter a month) and another 2-3 months to revise (with illustrations). With Sir William Davenant I want to create something special, so that'll take ages.

There are two things I couldn't do without. One is coffee. The other is my fantastically loyal, supportive and organised wife, Kim.

*****

I now get to tag a couple of authors who will pick up the baton and run with it, and I've chosen two great writers who are part of the Review Group on Facebook. I'll let the first introduce herself:

I’m Louise Rule, my first book Future Confronted was published in December 2013, and I am now researching my next book, the story of which will take me travelling from Scotland to England, and then to Italy. I am on the Admin Team of the Facebook group The Review Blog which I enjoy immensely.

Louise's blog can be found here.

My other chosen successor on this blog tour is Stuart S. Laing. Stuart writes about Scottish history - his posts on the Review Group Blog covering fascinating moments in Edinburgh's past are a joy to read, but it's his historical novels - the Robert Young of Newbiggin Mysteries - which really deserve attention.

Stuart's blog can be found here.

Finally, it remains for me only to thank Margaret Skea for inviting me to take part in this hop. And to thank you, dear reader, for perusing my musings.

Ciao!

Monday, 13 January 2014

The Grail - Final Chapter

It's here!!!

The last chapter of The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion has now gone live on the Moon Books blog!

So there we are. A year's work comes to an end, with a chapter which seeks to recapitulate where we've been and what we've learnt, and to carry much of that forwards - to anticipate, as it were, where we're going.

It's arguably one of the most contentious, controversial chapters I've ever written.

A few weeks now to go back through all the chapters and try to tidy up any loose ends. But, in the meantime, huge thanks to Trevor Greenfield at Moon Books for the opportunity, John M. Gist for the advice and feedback, and Lloyd Canning for the monthly illustrations.

The last chapter of The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion has now gone live on the Moon Books blog!

So there we are. A year's work comes to an end, with a chapter which seeks to recapitulate where we've been and what we've learnt, and to carry much of that forwards - to anticipate, as it were, where we're going.

It's arguably one of the most contentious, controversial chapters I've ever written.

A few weeks now to go back through all the chapters and try to tidy up any loose ends. But, in the meantime, huge thanks to Trevor Greenfield at Moon Books for the opportunity, John M. Gist for the advice and feedback, and Lloyd Canning for the monthly illustrations.

Wednesday, 18 December 2013

The Grail - Saints and Stones

The last but one chapter of The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion is now up on the Moon Books blog. In this 11th chapter, we break the news that the "Grail" can still be seen on Pictish symbol stones in very close proximity to the scene of Arthur's last battle.

It's a difficult chapter, I'll admit. Working this way (a chapter a month, published online, and then on to the next chapter) has been a very interesting experience, but not always an easy one. Usually, I'd write out several chapters, then go back and revise them, move on to the next chapters, go back, revise, move forwards, back, revise, onwards, rewrite a section, rewrite another section, complete the manuscript, then revise it ... But not this time! Oh no. A chapter, when it's done, goes up on the blog. It's published. And on we go to the next one.

I'm beginning to look forward to reading through the completed manuscript when the final chapter is published next month. It'll be interesting to see how (and if) the whole thing hangs together. How much repetition is there? What needs to go, what needs to be better explained ...

Anyway, the research has been fascinating. As has been receiving feedback on each chapter (work-in-progress) from my brother-in-arms, John Gist, and planning each of the chapter images with my very talented near-neighbour, Lloyd Canning. Lloyd lives round the corner from me; John lives in New Mexico. It's been an international collaboration!

A lot of new material has been unearthed during the course of this project, and I'm hopeful that the final chapter will put most of it into perspective. I look forward to being able to post the link.

Meanwhile, in other news, the Royal Shakespeare Company bookshop is now stocking Who Killed William Shakespeare?

"Made it, Ma! Top of the world!"

It's a difficult chapter, I'll admit. Working this way (a chapter a month, published online, and then on to the next chapter) has been a very interesting experience, but not always an easy one. Usually, I'd write out several chapters, then go back and revise them, move on to the next chapters, go back, revise, move forwards, back, revise, onwards, rewrite a section, rewrite another section, complete the manuscript, then revise it ... But not this time! Oh no. A chapter, when it's done, goes up on the blog. It's published. And on we go to the next one.

I'm beginning to look forward to reading through the completed manuscript when the final chapter is published next month. It'll be interesting to see how (and if) the whole thing hangs together. How much repetition is there? What needs to go, what needs to be better explained ...

Anyway, the research has been fascinating. As has been receiving feedback on each chapter (work-in-progress) from my brother-in-arms, John Gist, and planning each of the chapter images with my very talented near-neighbour, Lloyd Canning. Lloyd lives round the corner from me; John lives in New Mexico. It's been an international collaboration!

A lot of new material has been unearthed during the course of this project, and I'm hopeful that the final chapter will put most of it into perspective. I look forward to being able to post the link.

Meanwhile, in other news, the Royal Shakespeare Company bookshop is now stocking Who Killed William Shakespeare?

"Made it, Ma! Top of the world!"

Friday, 8 November 2013

The Grail - CAMLANN

Chapter 10 of The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - entitled "Camlann" - is now up on the Moon Books blog!

I've written about the Battle of Camlann before on this blog, and with The Grail I have been able to put the fruits of yet more research out there. I have finally (I believe) tracked down the original meaning of cam lann - which is how the place-name first appears - and it confirms that Artuir mac Aedain was the one and only Arthur of history.

There is quite a lot more detail given of the final battle in this chapter, especially in terms of topography (what the sources tell us about the scene and where those references show up on today's map), leaving precious little room for doubt as to where Arthur's last battle was fought. And all this builds up to a revelation which will be made in the next chapter:

The Grail can still be seen in the immediate vicinity of Arthur's last battle!

That chapter will be up in about a month's time. I'll let you know.

I've written about the Battle of Camlann before on this blog, and with The Grail I have been able to put the fruits of yet more research out there. I have finally (I believe) tracked down the original meaning of cam lann - which is how the place-name first appears - and it confirms that Artuir mac Aedain was the one and only Arthur of history.

There is quite a lot more detail given of the final battle in this chapter, especially in terms of topography (what the sources tell us about the scene and where those references show up on today's map), leaving precious little room for doubt as to where Arthur's last battle was fought. And all this builds up to a revelation which will be made in the next chapter:

The Grail can still be seen in the immediate vicinity of Arthur's last battle!

That chapter will be up in about a month's time. I'll let you know.

Labels:

Arthur,

Artuir mac Aedain,

Camlan,

Grail,

Moon Books

Thursday, 24 October 2013

Kitchen Witchcraft

Witch. It's such a troublesome word, isn't it? So many negative connotations.

Centuries of misinformation, prejudice and propaganda turned the very notion of "witchcraft" into something hideous and fearful. We see similar processes at work today - in the United States, for example, where a positive word like "liberal" (meaning generous, open-minded, and inclined towards favouring individual liberty) has been turned into a political insult. Whenever we see something like that happening - wherever a perfectly good word denoting a perfectly decent political or religious stance is transformed into a term of abuse, becoming a sort of catch-all "bogeyman" for the majority to fear and loathe - we have to question the motives of those who drive that semantic change.

One way or another, witchcraft is an extremely ancient pursuit. It's difficult to separate "witchcraft" from its companion concept, "paganism". Both have been enjoying something of a resurgence, lately - and, overall, that's a good thing, because this represents a return of sorts to an older and more natural way of doing things.

The term "pagan" means, simply, country-dweller (paganus). While the more elaborate cults flourished in the cities of the ancient world, those cities were utterly dependent on rural communities to provide the food for their markets and their tables. And those rural communities remained in touch with the processes of agriculture, the cycle of the seasons, the hardwork, care, attention and - yes - hope which are all necessary if we are to enjoy ample harvests.