The Future of History

Showing posts with label Aneirin. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Aneirin. Show all posts

Sunday, 17 August 2014

Alyth, the Scene of Arthur's Last Battle

While I work on Shakespeare's Son - my biography of Sir William Davenant, a man of whom I'm becoming increasingly fond - The Grail continues to make its way through the publishing process, courtesy of Moon Books. So, by way of a sneak preview, in this post I shall offer up some of the evidence for the location of Arthur's last battle.

The Battle of Circenn

You probably think Arthur's last battle was fought at a place called "Camlann". I've been unable to find any reference to that place-name before the Middle Ages. The very earliest mentions of anyone called Arthur in the records indicate that he died in a battle fought in Angus, Scotland.

Adomnan of Iona's Life of Columba (circa 697) tells us that Artur son of Aedan was present when his father was "ordained" king of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574. The saint predicted the fates of Aedan's sons, announcing that Artur would "fall in battle, slain by enemies". Adomnan assured his readers that this prophecy came true when Artur and at least one of his brothers was killed in a "battle of the Miathi".

The Miathi, or Maeatae, were a Pictish tribe: essentially, they held the low-lying lands to the south and east of the Highland massif. Another Latinate term for these people was Verturiones.

The Irish annals, which drew at least some of their information from the records kept by Columba's monks on the Isle of Iona, specify that Artur son of Aedan died in a "battle of Circenn". This refers to the Pictish province which was roughly contiguous with today's Angus and the Mearns. The term Circenn combined the Gaelic cir, meaning a "comb" or "crest", and cenn, "heads". Circenn, then, was the land of the Comb-heads. This tells us that the Miathi Picts modelled their appearance on their totem beast, the boar (rather like their compatriots in the Orkneys, the Orcoi, from orc - a young boar). Indeed, it is possible that the Latinate name for the Verturiones tribe combines verres and turio and indicates the "offshoots" or "offspring" of the "boar", while the very term "Pict" (variant, "Pecti", "Pecht") quite possibly derived from the Latin pecten, a "comb".

Now, let's look at "Camlann" - the traditional name for Arthur's last battle. Its first appearance in the records comes in an entry interpolated into the Welsh Annals, where it refers to a gueith cam lann or "strife of cam lann". By the time this came to be written down, the region in which Artur son of Aedan died was speaking a version of Northumbrian Old English which became the dialect known as Lowland Scots. In that dialect, cam lann would mean "comb land".

In other words, "Camlann" is merely an anglicised version of the Gaelic Circenn, the land of the "Comb-heads" in which the first Arthur on record fell in a cataclysmic battle.

Culhwch and Olwen

One of the oldest of the Welsh (i.e. British) tales to feature Arthur is that of Culhwch ac Olwen. It forms a sort of mythologised, potted account of Arthur's career, culminating in the desperate and bloody hunt for a king who - for his sins - was turned into a boar. This hunt begins with a violent amphibious landing, at a site which can be identified as Cruden Bay, on the Aberdeenshire coast, after which Arthur is met by the "saints of Ireland" who "besought his protection". The dreadful Boar-King is challenged and chased from Esgeir Oerfel, the "Cold Ridge" of the Grampians, the Boar-King making his way across country towards Llwch Tawy (Loch Tay) before he is intercepted by Arthur and his men and driven into a river.

In The King Arthur Conspiracy I identified the treacherous Boar-King as Morgan the Wealthy, a renegade British prince who abducted Arthur's wife, Gwenhwyfar, and escaped into the land of the Miathi Picts (his bolt hole appears to have been the fortified Hill of Tillymorgan in Strathbogie). The site where Morgan finally came to grief is marked by the "Morganstone" on the west bank of the River Ericht, a short distance to the west of the Hill of Alyth in the great vale of Strathmore in Angus.

Arthurian Connections with Alyth

Before we proceed, let us consider some ancient references to Arthur and his family in the context of Alyth and its immediate vicinity.

In addition to having a son named Artur or Artuir, King Aedan of the Scots had a daughter called Muirgein. According to Whitley Stokes, editing and translating the Martyrology of a 9th-century Irish monk called Oengus, Muirgein daughter of Aedan was born "in Bealach Gabrain".

The inability of certain scholars to find a "Bealach Gabrain" in Scotland has led some to argue that Muirgein daughter of Aedan was utterly unconnected with Artur son of Aedan. But place-names evolve. The Gaelic term bealach, meaning a "pass" or "gorge", usually appears as "Balloch" on today's maps. There is a "Balloch" which runs along the feet of Barry Hill and the adjacent Hill of Alyth in Strathmore.

Furthermore, this "Balloch" or bealach was in a region named after the grandfather of Artur and Muirgein. Gabran was the father of Aedan. He ruled the Scots for twenty years until his death in about AD 559 and gave his name to the region of Gowrie (a corruption of Gabran). The "Balloch" near Alyth was in Gabran's land (Gabrain) and lies close to the town of Blairgowrie, which also recalls the name of Arthur's grandfather. The "Balloch" at the foot of the Hill of Alyth was almost certainly the "Bealach Gabrain" or "pass of Gowrie" where Arthur's (half-)sister, Muirgein daughter of Aedan mac Gabrain, was born. To pretend that the Balloch of Gowrie could not have been "Bealach Gabrain" because they are not spelled the same way these days is tantamount to claiming that Londinium and London could not have been the same place.

So Arthur's sister, Muirgein (latterly, Morgan le Fay), was born near Alyth. Writing in about 1527, the Scottish historian Hector Boece also indicated that Arthur's wife was buried at Meigle, which is just a mile or two south of Alyth. Hector Boece's local tradition recalled Gwenhwyfar as Vanora (via Guanora) and claimed that she had been held hostage in the Iron Age hill-fort atop Barry Hill, adjacent to the Hill of Alyth, before she was executed and buried in what is now the kirkyard at Meigle. A carved Pictish standing stone, now on display at the Meigle museum, reputedly depicts the execution or burial of Arthur's wife.

Y Gododdin

One of the best sources of information about Arthur's last battle is the ancient epic, Y Gododdin. This was composed and sung by Aneirin, a British bard of the Old North, and can be dated to circa AD 600 (the date of Arthur's last battle is given in the Irish annals as, variously, AD 594 and 596).

Unfortunately, the relevance of Aneirin's elegiac tribute to the warriors of Lothian (the "Gododdin") has been missed by scholars who want to believe that the poem bemoans the destruction of a British war-band from the Edinburgh area which had the misfortune to be wiped out at a mythical battle fought at Catterick in North Yorkshire. No evidence exists that any such battle was fought. The Angles (forerunners of the English) preferred not to recollect their defeats but were happy to remember, and to boast about, their victories. If the Angles of Northumbria had indeed obliterated a British band of heroes from Lothian at Catterick, we might assume that they would have remembered doing so. And no scholar has yet explained the presence of "Irishman and Picts" at this imaginary battle in Anglian territory.

A verse or two of Y G[ododdin, added at a later date than the original composition, described a battle fought in Scotland (Strathcarron) in AD 642 and the death in that battle of a Scottish king who just happened to be a nephew of Artur son of Aedan. This interpolation does at least suggest that the subject of the original poem was a battle fought in roughly the same area (Scotland) by the family of Artur and his father Aedan. The Y Gododdin poem also mentions various famous warriors who appear in the early accounts of Arthur's career and who were contemporary with Artur son of Aedan.

One surviving version of Y Gododdin even mentions Artur/Artuir by name:

Gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef Arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

Confused by the misidentification of the battle sung about by Aneirin in Y Gododdin, and the assumption that Arthur himself could not have been present at that battle, scholars have persistently mistranslated this verse - mostly in an attempt to render the second half of the second line, "He was no Arthur". But Aneirin's verse should properly be translated thus:

Black ravens [warriors] sang in praise of the hero [Welsh, arwr]

of Circenn [transliterated into Welsh as "caer ceni"]. He blamed Arthur;

the dogs cursed in return for our wailing/lamentation ...

Aneirin indicated, in his Y Gododdin elegy, precisely where the final battle took place:

Eil with gwelydeint amallet

y gat veirch ae seirch greulet

bit en anysgoget bit get ...

Which translates as:

Again they came into view around the alled,

the battle-horses and the bloody armour,

still steadfast, still united ...

The "alled" was Aneirin's Welsh-language attempt at the Gaelic Allaid - also Ailt - or the Hill of Alyth.

Breuddwyd Rhonabwy

The extraordinary medieval Welsh tale of The Dream of Rhonabwy actually provides a description of the scene in the hours before Arthur's last battle was fought. The visionary seer, Rhonabwy, finds himself crossing a great plain with a river running through it (Strathmore). He is met by a character call Iddog, "Churn of Britain", who admits that it was he who caused the cataclysmic "battle of Camlan" by betraying Arthur. In company with Iddog, Rhonabwy approaches the "Ford of the Cross" (Rhyd-y-Groes) on the river. A great army is encamped on either side of the road and Arthur is seated on a little flat islet in the river, beside the ford.

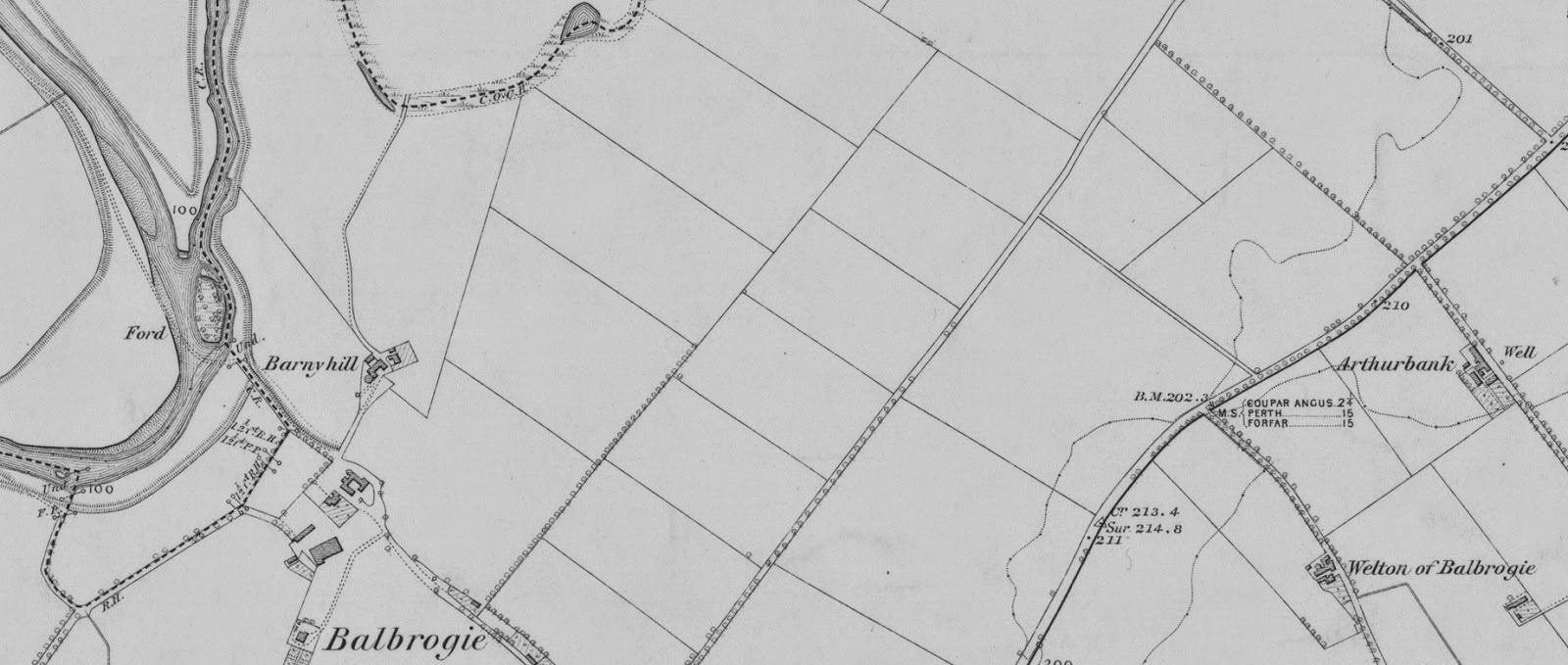

The topography precisely matches the detail from a 19th-century Ordnance Survey map of the area around Alyth seen at the top of this post. On the right-hand side of the detail is the ridge known as Arthurbank, which lies along the River Isla, opposite the junction of the River Ericht with the River Isla (a few miles down the Ericht from the site of the Morganstone). A little flat islet lies in the River Isla, close to the Arthurbank shore, and a ford runs alongside this little islet, exactly as described in the Welsh account of Rhonabwy's dream.

Aneirin also mentioned this ford in his Y Gododdin poem as rhyd benclwyd - the "ford" of the "grey" or "holy mount". There is, indeed, a Greymount marked on the map, a short distance to the north of the ford on the Isla. In his Agriculture of Perthshire, published in 1799, the Rev. Dr Robertson described the discovery of a "large Druidical temple" at Coupar Grange, adjacent to this ford. A standing stone found in this "temple" would no doubt have been rebranded a "cross" by the early Christians, so that the ford across the Isla, beside the little flat islet, would have become known as the Ford of the Cross (Rhyd-y-Groes), as described in The Dream of Rhonabwy, or the "Ford of the Grey/Holy Mount" (rhyd benclwyd) as described by Aneirin.

Until the late 18th century, an Arthurstone stood at the south-eastern edge of the Arthurbank ridge (its presence is still marked on the map). This Arthurstone corresponds to the Morganstone, a few miles away up the River Ericht, and marks the spot where Arthur fell in his battle with the Boar-King of the Miathi Picts in the land of the "crested" Comb-heads, Camlann.

The Head of the Valley of Sorrow

After the battle, Arthur's wife Gwenhwyfar was executed and buried only a mile or so away at Meigle. The legend of Culhwch and Olwen (which, interestingly, features a treacherous individual identified as Grugyn, who also appears in Aneirin's Y Gododdin) tells us that, after the battle at the river with the dangerous Boar-King, Arthur and his heroes once more "set out for the North" to overcome a fearsome witch. She was found inside a cave at Penn Nant Gofid - the "Head of the Valley of Sorrow"- on "the confines of Hell" (which we can interpret as the edge of the territory controlled by those boar-like Miathi Picts). The Welsh gofid ("sorrow/trouble/affiction/grief") appears to have been something of a pun, for another Welsh word for sorrow or grief is alaeth (compare Ailt, Allaid and Alyth, the "Head of the Valley of Alyth" being the very hill on which Arthur's wife is rumoured to have been held prisoner before her execution and burial nearby at Meigle).

In the Welsh tale, this witch is known as Orddu (that is, Gorddu - "Very Black"). A similar legend from the Isle of Mull, whose Arthurian associations have been overlooked for far too long, names the troublesome wife as Corr-dhu ("Black-Crane").

We might also note that the 9th-century Welsh monk known as Nennius described a "wonder" of Scotland in the form of "a valley in Angus, in which shouting is heard every Monday night; Glend Ailbe is its name, and it is not known who makes this noise."

Nennius's Glend Ailbe seems to be a corruption of the Gaelic word for a valley (glen) and the River Isla, or perhaps the Allaid or Hill of Alyth, which dominates the vale of Strathmore. The mysterious shouting in this "Valley of Sorrow" was reputedly heard ever Monday night. And we know from Aneirin's eye-witness account of Arthur's last battle that it came to an end on a Monday.

This is just some of the evidence for Arthur having fallen in the vicinity of Alyth. There is plenty more to come in The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - including descriptions of the Pictish symbol stones, found close to the site of that battle, which actually depict the Grail in use!

I'll let you know when the book is about to be published.

Sunday, 18 August 2013

Lost in Translation

My first paid commission as a writer was to adapt the libretto of a Danish comic opera into English.

It was an odd commission. For a start, I don't speak Danish. And I was at drama school at the time. In fact, I was touring Holland and Belgium, playing in a different venue in a different town every night. Didn't leave much time.

One thing I did insist on doing was replicating the rhyme scheme of the original Danish. The other translations I was given hadn't even tried to do that.

Oh, and it was a comic opera. So a gag or two seemed requisite.

Anyway, that little trip down Memory Boulevard was inspired by one of this week's niggling little problems: interpreting the old British poems which deal with Arthur. It's not the first time I've grappled with some of these, and I doubt it'll be the last.

The image from China (above) illustrates the problem (I won't show you how a Chinese menu managed to render Crispy Fried Duck into English - suffice it to say that it was an alarming, though very amusing, image). If you take a word from one language and spin it into another, something weird might happen. The Book of Heroic Failures mentions the gloriously bizarre English-Portugese phrasebook produced by Pedro Carolino in 1883. Pedro didn't speak English, so his useful phrases have a peculiar charm of their own.

An example - his sample dialogue, "For to ride a horse", has as its opening gambit:

"Here is a horse who have bad looks. Give me another. I will not that. He not sall how to march, he is pursy, he is foundered. Don't you are ashamed to give me a jade as like? he is undshoed, he is with nails up".

Which would surely mark you out as a tourist. (And who could forget the wonderful English-language notes accompanying a production of Carmen, which included the dramatic chorus, "Toreador, toreador, oh for the balls of a toreador"?)

Great fun. But a problem, too. For even the most earnest of scholars can come a cropper when trying to translate something which belongs to another time and place.

In one of my chapters of The Grail, recently posted on the Moon Books blog, I included a few lines from the marvellous Y Gododdin poem of Aneirin (circa AD 600). I gave the three lines in archaic Welsh, followed by Skene's 19th century translation of those lines, then a more general 20th century translation, then my own translation.

Before long, an argument had arisen. I had done it all wrong, apparently, by departing from the text set down by my betters. On one point, one of my interlocutors was absolutely right - I had wrongly transcribed one of the original Welsh words, which has since led to three days of obsessive research and revision to try and pin down the meaning of one word.

One word. Three days. About a dozen variants played with and discarded. And this word (it's only four letters, by the way - ceni, if you must know) had already been translated in wildly different ways by acknowledged experts.

Well, I've finally come up with what I believe it meant, and that's gone into my manuscript of The Grail (but it's not online - you'll have to wait for the book). But it was all a wonderful reminder of the great big problems of translation.

Context. If you don't know the context in which the original words were created, you're not likely to get the meaning right when you convert them into modern English.

Mindset. Language is not just words, it's a way of looking at, understanding and interpreting the world. It's a means of expression, and what is expressed is how a person - and a culture - comprehends the world around them. A different culture means a different way of perceiving and relating to the world. They way they expressed their thoughts made sense to them: it might make no sense at all if you just alter those words to their nearest English equivalents.

You don't have to go back to Welsh poems from 6th century Britain to encounter these problems. For the first twenty years of my research into William Shakespeare, I suffered from a major handicap: I didn't really enjoy reading or watching his plays. No, I'll go further: I found them mind-bendingly obtuse, obscure, verbose and impenetrable. Not much fun at all.

Reading a Shakespeare play (or going to see one) felt a bit like going to the dentist. It would no doubt be a horrible experience, but I'd be the better for having submitted to it.

What was wrong wasn't me. It was what I'd been taught about Shakespeare - or, rather, what I hadn't been taught. No one had given me the vital key to understanding Shakespeare's writings (the key, by the way, is the Reformation). Once I found that key, everything changed. Now I can read a Shakespeare play for pleasure. I find his work fascinating, lucid, hugely emotional, terrifying, disturbing and - most of all - relevant. He's remarkably clear, once you get your head round the context (his world) and the mindset (how he saw it).

The poetry of Arthur's age has been persistently misinterpreted because the scholars who come to it know a fair deal about the language it's written in, but very little about the context (and, I often feel, next to nothing about the mindset). But that's what makes working on these poems so fascinating. Not only are you solving puzzles, but you're learning all the time about the world these people lived in and they way they saw it.

A "straight" translation tends to come across as gibberish, which is then re-interpreted through some modern idea of what people might have believed back then (for example, an excellent poem which describes Arthur's funeral has often been interpreted, somewhat crassly, as an account of a raid undertaken into the Otherworld to steal stuff). But whether we're reading Shakespeare or trying to get our heads round what the major poets of Arthur's day were saying, the least we can do is listen to them. Don't try to force an interpretation onto them (as so many directors do with Shakespeare, and so many critics have done). Don't say, "This word means that. It can only mean that. There is no other possible meaning." Listen to them.

It might take days. Or weeks. Or months. Or years. But the rewards can be amazing. As if another person's world has suddenly opened up to you. And you can see things as they saw them.

It was an odd commission. For a start, I don't speak Danish. And I was at drama school at the time. In fact, I was touring Holland and Belgium, playing in a different venue in a different town every night. Didn't leave much time.

One thing I did insist on doing was replicating the rhyme scheme of the original Danish. The other translations I was given hadn't even tried to do that.

Oh, and it was a comic opera. So a gag or two seemed requisite.

Anyway, that little trip down Memory Boulevard was inspired by one of this week's niggling little problems: interpreting the old British poems which deal with Arthur. It's not the first time I've grappled with some of these, and I doubt it'll be the last.

The image from China (above) illustrates the problem (I won't show you how a Chinese menu managed to render Crispy Fried Duck into English - suffice it to say that it was an alarming, though very amusing, image). If you take a word from one language and spin it into another, something weird might happen. The Book of Heroic Failures mentions the gloriously bizarre English-Portugese phrasebook produced by Pedro Carolino in 1883. Pedro didn't speak English, so his useful phrases have a peculiar charm of their own.

An example - his sample dialogue, "For to ride a horse", has as its opening gambit:

"Here is a horse who have bad looks. Give me another. I will not that. He not sall how to march, he is pursy, he is foundered. Don't you are ashamed to give me a jade as like? he is undshoed, he is with nails up".

Which would surely mark you out as a tourist. (And who could forget the wonderful English-language notes accompanying a production of Carmen, which included the dramatic chorus, "Toreador, toreador, oh for the balls of a toreador"?)

Great fun. But a problem, too. For even the most earnest of scholars can come a cropper when trying to translate something which belongs to another time and place.

In one of my chapters of The Grail, recently posted on the Moon Books blog, I included a few lines from the marvellous Y Gododdin poem of Aneirin (circa AD 600). I gave the three lines in archaic Welsh, followed by Skene's 19th century translation of those lines, then a more general 20th century translation, then my own translation.

Before long, an argument had arisen. I had done it all wrong, apparently, by departing from the text set down by my betters. On one point, one of my interlocutors was absolutely right - I had wrongly transcribed one of the original Welsh words, which has since led to three days of obsessive research and revision to try and pin down the meaning of one word.

One word. Three days. About a dozen variants played with and discarded. And this word (it's only four letters, by the way - ceni, if you must know) had already been translated in wildly different ways by acknowledged experts.

Well, I've finally come up with what I believe it meant, and that's gone into my manuscript of The Grail (but it's not online - you'll have to wait for the book). But it was all a wonderful reminder of the great big problems of translation.

Context. If you don't know the context in which the original words were created, you're not likely to get the meaning right when you convert them into modern English.

Mindset. Language is not just words, it's a way of looking at, understanding and interpreting the world. It's a means of expression, and what is expressed is how a person - and a culture - comprehends the world around them. A different culture means a different way of perceiving and relating to the world. They way they expressed their thoughts made sense to them: it might make no sense at all if you just alter those words to their nearest English equivalents.

You don't have to go back to Welsh poems from 6th century Britain to encounter these problems. For the first twenty years of my research into William Shakespeare, I suffered from a major handicap: I didn't really enjoy reading or watching his plays. No, I'll go further: I found them mind-bendingly obtuse, obscure, verbose and impenetrable. Not much fun at all.

Reading a Shakespeare play (or going to see one) felt a bit like going to the dentist. It would no doubt be a horrible experience, but I'd be the better for having submitted to it.

What was wrong wasn't me. It was what I'd been taught about Shakespeare - or, rather, what I hadn't been taught. No one had given me the vital key to understanding Shakespeare's writings (the key, by the way, is the Reformation). Once I found that key, everything changed. Now I can read a Shakespeare play for pleasure. I find his work fascinating, lucid, hugely emotional, terrifying, disturbing and - most of all - relevant. He's remarkably clear, once you get your head round the context (his world) and the mindset (how he saw it).

The poetry of Arthur's age has been persistently misinterpreted because the scholars who come to it know a fair deal about the language it's written in, but very little about the context (and, I often feel, next to nothing about the mindset). But that's what makes working on these poems so fascinating. Not only are you solving puzzles, but you're learning all the time about the world these people lived in and they way they saw it.

A "straight" translation tends to come across as gibberish, which is then re-interpreted through some modern idea of what people might have believed back then (for example, an excellent poem which describes Arthur's funeral has often been interpreted, somewhat crassly, as an account of a raid undertaken into the Otherworld to steal stuff). But whether we're reading Shakespeare or trying to get our heads round what the major poets of Arthur's day were saying, the least we can do is listen to them. Don't try to force an interpretation onto them (as so many directors do with Shakespeare, and so many critics have done). Don't say, "This word means that. It can only mean that. There is no other possible meaning." Listen to them.

It might take days. Or weeks. Or months. Or years. But the rewards can be amazing. As if another person's world has suddenly opened up to you. And you can see things as they saw them.

Labels:

Aneirin,

Grail,

Moon Books,

Reformation,

Shakespeare,

Y Gododdin

Monday, 13 May 2013

Making Sense of "Y Gododdin"

I'm working ahead on the Grail book (The Grail: Relic of an Ancient Religion, being published in monthly instalments on the Moon Books website/blog). Basically, the proofs of Who Killed William Shakespeare? will be arriving soon, so I'm making sure that the Grail book is advanced enough that I won't fall behind deadline with it when I take a couple of weeks out to focus on the story of Shakespeare and his skull.

So I've been reviewing the historical sources for Arthur. I've looked at what many scholars consider to be the sole historical sources, and then I've explored the others. The latter have a great deal to tell us about Arthur but are usually ignored.

They are ignored for one of two reasons:

1) scholars have not understood the context of the sources and have therefore wrongly assigned them;

2) scholars don't want to entertain the merest possibility that Arthur wasn't a Romanised Christian operating in southern Britain in the late 5th/early 6th centuries.

Evidence which does not support the latter view tends to be discounted as inadmissable. If it is considered at all. But basically, it does not correspond to the Arthurian stereotype.

In fact, there is no evidence at all for an Arthur active in the south. None. Not a shred.

There is, however, plenty of evidence to link him with the North. And not in the early 6th century, but in the last quarter of that century.

Take Y Gododdin. This was composed by Aneirin, a princely poet of North Britain, and was probably first sung in or near Edinburgh in about the year 600.

Of the two surviving versions of Y Gododdin (the "title" refers to the warriors of Lothian, of which the capital was Edinburgh, the site of Arthur's Seat), the oldest includes a direct reference to Arthur. Here it is in the original Old Welsh:

Gochore brein du ar uur

Caer cein bei ef arthur

Rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

(These are the last words to appear on the page of the Y Gododdin text in the photo above).

This was translated by W.F. Skene in the 19th century thus:

Black ravens croaked on the wall

Of the beautiful Caer. He was an Arthur

In the midst of the exhausting conflict ...

Skene's translation gives the impression that a certain warrior of the Britons was so impressive that he was "an Arthur". That was too much for some scholars, who have tended to translate the original passage along the following lines:

He glutted black ravens on the rampart

Of the fortress, though he was no Arthur

He did mighty deeds in battle ...

So, the warrior in question was "no Arthur". He was good, but he wasn't that good. And the implication appears to be that "Arthur", whoever he was, was a sort of yardstick by which warriors were measured (and apparently found wanting). It follows that this original Arthur had belonged to another time and place. It is as if we might say of someone today, "He was a great president, though he was no Lincoln."

I've long had a problem with this familiar interpretation of Aneirin's lines. Not least of all because I couldn't see where the negative element in the lines came in. I couldn't understand where the scholarly translators had found that negative. If the lines did in fact mean "he was no Arthur", you'd expect something in the original words to indicate "no" or "not". But that negative is nowhere to be seen.

Unless the scholars were interpreting the Welsh word cein by way of the Germanic kein. Which would be a peculiar thing to do. Like using a Danish dictionary to translate a statement in French.

Here's what I make of the lines, from the Old Welsh original:

Black ravens sang [praises] over the man-servant

Of Cian's fortress; he blamed Arthur,

The dogs cursed in return for our wailing ...

Okay, that's a very different interpretation. It assumes that Gochore relates to the archaic Welsh gochanu, "to sing, to praise", and that uur should not be read as mur ("wall") but as [g]wr ("vassal"). There is a translation in there which comes by way of Irish/Scottish Gaelic: cein, a variant of the genitive form of Cian, a personal name. But then, Welsh and Gaelic are related - as Celtic languages - while English is a Germanic language and is unlikely to offer many clues as to the meaning of Y Gododdin in its original Welsh.

The half-line bei ef arthur comes out as "he blamed Arthur" (Welsh beio, "to blame", "to accuse", with ef being the third person masculine pronoun, "he").

Now, this interpretation brings Arthur somewhat closer to the action. Whatever had happened, the individual being described by Aneirin at this stage in his elegy "blamed Arthur" for it. The "Black ravens" were warriors (they appear elsewhere in Arthurian literature, as in the Dream of Rhonabwy, a story from the Mabinogion, in which Arthur's soldiers attack, and are they attacked by, the "ravens" of Owain son of Urien). They were singing and wailing. A funeral ceremony is suggested. But somebody there blamed Arthur. The "dogs" who cursed the warriors in response to their songs of praise appear to have taken the side of whoever it was who blamed Arthur for whatever it was that had happened.

Arthur, then, was not some heroic figure of legend or distant memory. He was, according to one view, the cause of the military catastrophe, the devastating defeat, described by the poet Aneirin. Whatever had gone wrong at that final battle - which saw the effective annihilation of the army of Lothian - Arthur was held responsible for it (at least by the individual who had his cursing "dogs" with him).

There is more that I could say about the scenario as hinted at in those few words from the ancient Welsh poem. A description, along with partial explanation, is given in my book The King Arthur Conspiracy, and was partly drawn from the poetry of Taliesin, a contemporary of Arthur who also warrants a mention in Y Gododdin.

The point to make here, though, is that consistently translating the Y Gododdin lines through mere guesswork (inserting negatives which aren't there, for example) leads to gross misinterpretations. And those, in turn, distance us from Arthur by excluding - and/or misrepresenting - the available evidence.

The only real reason why scholars have misinterpreted the lines, making out that they mean something very different to what they actually say, is because they don't want to countenance an Arthur of the North.

Whereas the North is, in fact, precisely where Arthur is to be found. In the company of those other warriors named in Y Gododdin who are also named in the legends of Arthur.

So please, folks, can we stop pretending that Arthur's contemporary poets said something which they manifestly didn't? We cannot ignore, dismiss or disallow a vitally important poem like Y Gododdin just because we're not prepared to translate it properly.

Unless, of course, the plan is to avoid identifying Arthur. And why, I wonder, would anyone want to do that.

***

NB: It has been pointed out to me, quite rightly, that the actual words in the Y Gododdin text are caer ceni bei ef arthur. I had, at the time, gone with Professor W.F. Skene's interpretation, substituting cein (cain - 'fair', 'beautiful') for ceni.

The meaning of ceni is unclear. It could relate to caen, plural caenau, or cen, indicating a 'layer' or 'coating'. Caer ceni might therefore be the 'layered fort'. There is also cyni - 'anguish', 'adversity' - suggesting a 'Fort of Distress', which would be appropriate.

Another possibility, though, is that ceni was a sort of loan word from the Irish. The Gaelic ceann - genitive and plural cinn - derives from the Old Irish cenn, a 'head', 'chief', 'commander', 'headland', 'point' or 'extremity'. The suffix i might therefore be recognised as I, the Gaelic name for the Isle of Iona, where (I believe) Arthur was buried.

This offers a couple of possible interpretations for the Y Gododdin lines:

"Black ravens sang [praises] over the man-servant

Of the fortress of the Chief-of-Iona/Far end of Iona. He blamed Arthur ..."

or:

"Black ravens sang [praises] over the man

Of the fortress. The Master-of-Iona, he blamed Arthur;

The dogs cursed in return for our weeping ..."

Getting this right is important, of course. The art of translation demands both accuracy and an awareness of context. Understanding Y Gododdin, or any other poem of time, requires more than just a rendering of the old Welsh words into new English ones - for that, on its own, can be misleading. We need to understand, as far as possible, the circumstances in which the poem was composed. It is this lack of understanding which, I would say, has led scholars to try and interpose a distance between Arthur and Y Gododdin. Remove that artificial distance, and the poem begins to yield up its treasures.

So I've been reviewing the historical sources for Arthur. I've looked at what many scholars consider to be the sole historical sources, and then I've explored the others. The latter have a great deal to tell us about Arthur but are usually ignored.

They are ignored for one of two reasons:

1) scholars have not understood the context of the sources and have therefore wrongly assigned them;

2) scholars don't want to entertain the merest possibility that Arthur wasn't a Romanised Christian operating in southern Britain in the late 5th/early 6th centuries.

Evidence which does not support the latter view tends to be discounted as inadmissable. If it is considered at all. But basically, it does not correspond to the Arthurian stereotype.

In fact, there is no evidence at all for an Arthur active in the south. None. Not a shred.

There is, however, plenty of evidence to link him with the North. And not in the early 6th century, but in the last quarter of that century.

Take Y Gododdin. This was composed by Aneirin, a princely poet of North Britain, and was probably first sung in or near Edinburgh in about the year 600.

Of the two surviving versions of Y Gododdin (the "title" refers to the warriors of Lothian, of which the capital was Edinburgh, the site of Arthur's Seat), the oldest includes a direct reference to Arthur. Here it is in the original Old Welsh:

Gochore brein du ar uur

Caer cein bei ef arthur

Rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

(These are the last words to appear on the page of the Y Gododdin text in the photo above).

This was translated by W.F. Skene in the 19th century thus:

Black ravens croaked on the wall

Of the beautiful Caer. He was an Arthur

In the midst of the exhausting conflict ...

Skene's translation gives the impression that a certain warrior of the Britons was so impressive that he was "an Arthur". That was too much for some scholars, who have tended to translate the original passage along the following lines:

He glutted black ravens on the rampart

Of the fortress, though he was no Arthur

He did mighty deeds in battle ...

So, the warrior in question was "no Arthur". He was good, but he wasn't that good. And the implication appears to be that "Arthur", whoever he was, was a sort of yardstick by which warriors were measured (and apparently found wanting). It follows that this original Arthur had belonged to another time and place. It is as if we might say of someone today, "He was a great president, though he was no Lincoln."

I've long had a problem with this familiar interpretation of Aneirin's lines. Not least of all because I couldn't see where the negative element in the lines came in. I couldn't understand where the scholarly translators had found that negative. If the lines did in fact mean "he was no Arthur", you'd expect something in the original words to indicate "no" or "not". But that negative is nowhere to be seen.

Unless the scholars were interpreting the Welsh word cein by way of the Germanic kein. Which would be a peculiar thing to do. Like using a Danish dictionary to translate a statement in French.

Here's what I make of the lines, from the Old Welsh original:

Black ravens sang [praises] over the man-servant

Of Cian's fortress; he blamed Arthur,

The dogs cursed in return for our wailing ...

Okay, that's a very different interpretation. It assumes that Gochore relates to the archaic Welsh gochanu, "to sing, to praise", and that uur should not be read as mur ("wall") but as [g]wr ("vassal"). There is a translation in there which comes by way of Irish/Scottish Gaelic: cein, a variant of the genitive form of Cian, a personal name. But then, Welsh and Gaelic are related - as Celtic languages - while English is a Germanic language and is unlikely to offer many clues as to the meaning of Y Gododdin in its original Welsh.

The half-line bei ef arthur comes out as "he blamed Arthur" (Welsh beio, "to blame", "to accuse", with ef being the third person masculine pronoun, "he").

Now, this interpretation brings Arthur somewhat closer to the action. Whatever had happened, the individual being described by Aneirin at this stage in his elegy "blamed Arthur" for it. The "Black ravens" were warriors (they appear elsewhere in Arthurian literature, as in the Dream of Rhonabwy, a story from the Mabinogion, in which Arthur's soldiers attack, and are they attacked by, the "ravens" of Owain son of Urien). They were singing and wailing. A funeral ceremony is suggested. But somebody there blamed Arthur. The "dogs" who cursed the warriors in response to their songs of praise appear to have taken the side of whoever it was who blamed Arthur for whatever it was that had happened.

Arthur, then, was not some heroic figure of legend or distant memory. He was, according to one view, the cause of the military catastrophe, the devastating defeat, described by the poet Aneirin. Whatever had gone wrong at that final battle - which saw the effective annihilation of the army of Lothian - Arthur was held responsible for it (at least by the individual who had his cursing "dogs" with him).

There is more that I could say about the scenario as hinted at in those few words from the ancient Welsh poem. A description, along with partial explanation, is given in my book The King Arthur Conspiracy, and was partly drawn from the poetry of Taliesin, a contemporary of Arthur who also warrants a mention in Y Gododdin.

The point to make here, though, is that consistently translating the Y Gododdin lines through mere guesswork (inserting negatives which aren't there, for example) leads to gross misinterpretations. And those, in turn, distance us from Arthur by excluding - and/or misrepresenting - the available evidence.

The only real reason why scholars have misinterpreted the lines, making out that they mean something very different to what they actually say, is because they don't want to countenance an Arthur of the North.

Whereas the North is, in fact, precisely where Arthur is to be found. In the company of those other warriors named in Y Gododdin who are also named in the legends of Arthur.

So please, folks, can we stop pretending that Arthur's contemporary poets said something which they manifestly didn't? We cannot ignore, dismiss or disallow a vitally important poem like Y Gododdin just because we're not prepared to translate it properly.

Unless, of course, the plan is to avoid identifying Arthur. And why, I wonder, would anyone want to do that.

***

NB: It has been pointed out to me, quite rightly, that the actual words in the Y Gododdin text are caer ceni bei ef arthur. I had, at the time, gone with Professor W.F. Skene's interpretation, substituting cein (cain - 'fair', 'beautiful') for ceni.

The meaning of ceni is unclear. It could relate to caen, plural caenau, or cen, indicating a 'layer' or 'coating'. Caer ceni might therefore be the 'layered fort'. There is also cyni - 'anguish', 'adversity' - suggesting a 'Fort of Distress', which would be appropriate.

Another possibility, though, is that ceni was a sort of loan word from the Irish. The Gaelic ceann - genitive and plural cinn - derives from the Old Irish cenn, a 'head', 'chief', 'commander', 'headland', 'point' or 'extremity'. The suffix i might therefore be recognised as I, the Gaelic name for the Isle of Iona, where (I believe) Arthur was buried.

This offers a couple of possible interpretations for the Y Gododdin lines:

"Black ravens sang [praises] over the man-servant

Of the fortress of the Chief-of-Iona/Far end of Iona. He blamed Arthur ..."

or:

"Black ravens sang [praises] over the man

Of the fortress. The Master-of-Iona, he blamed Arthur;

The dogs cursed in return for our weeping ..."

Getting this right is important, of course. The art of translation demands both accuracy and an awareness of context. Understanding Y Gododdin, or any other poem of time, requires more than just a rendering of the old Welsh words into new English ones - for that, on its own, can be misleading. We need to understand, as far as possible, the circumstances in which the poem was composed. It is this lack of understanding which, I would say, has led scholars to try and interpose a distance between Arthur and Y Gododdin. Remove that artificial distance, and the poem begins to yield up its treasures.

Saturday, 10 March 2012

Tunnel Vision

First of all - apologies, folks, for the lack of recent posts. I'll soon be announcing some exciting news about my Shakespeare project.

But Arthur comes first. Literally; The King Arthur Conspiracy - How a Scottish Prince Became a Mythical Hero is due out this summer. I'm expecting the proofs to arrive in a matter of weeks.

Of course, there are many who will scoff at the very idea of a Scottish 'King' Arthur. It's considered heretical in some quarters even to mention the possibility that Arthur was a Scot. This has nothing whatsoever to do with history, though - only with the prejudices of the self-proclaimed Arthurian "experts".

Let me show you how it works. We'll start by looking at the early sources for the legends of Arthur.

Gildas Sapiens ('Gildas the Wise', or St Gildas) wrote his De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae - 'On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain' - sometime around the year 550. His open letter is something of a cornerstone in Arthur studies, even though Gildas made no mention at all of anyone called Arthur. He did, however, refer to a 'siege of Badon Hill' (obsessionis Badonici montis), which took place in the year of his birth. Scholars have failed to agree on when that might have been or where the siege might have taken place, but they generally assume that Arthur was there.

Nennius is the name given to a Welsh monk who compiled a 'History of the Britons' - Historia Brittonum- in about 820. Nennius didn't just mention Arthur: he described him as dux bellorum ('Duke of Battles') and listed twelve victories which Arthur achieved against the Saxons. The twelfth of these was fought on 'Mount Badon'. There is no particularly good reason to think that the battle on Mount Badon referred to by Nennius was the same as the 'siege of Badon Hill' mentioned earlier by Gildas, but in the main scholars have leapt to that conclusion, and by doing so have confused matters no end.

Bede was a Northumbrian churchman who wrote the seminal 'Ecclesiastical History of the English People'. Note that Bede's people were 'English' - the Angles, in other words, who were Arthur's enemies. The Anglo-Saxons were not very fond of recollecting their defeats in battle. Bede does not mention Arthur.

Annales Cambriae - the 'Annals of Wales' - were compiled by monks towards the end of the tenth century. They are another source of rampant confusion. Many years after the events, two entries were interpolated into the annals, and they both stick out like sore thumbs:

518 - The Battle of Badon in which Arthur carries the Cross of Our Lord Jesus Christ for three days and nights on his shoulders and the Britons were victors

539 - The battle of Camlann, in which Arthur and Medrawt fell; and there was plague in Britain and Ireland.

Neither of those dates are in any way relevant to the historical Arthur. They were invented, retrospectively, by Christian scribes.

And that, as they say, is that. Everything else is medieval fantasy or guesswork. These are the official early sources for Arthur - Gildas, Nennius, Bede and the Welsh Annals - and only two of those four even mention him by name!

Except that those are not the only documentary sources for the historical Arthur. Far from it.

There is, for example, the Vita Sanctae Columbae ('Life of St Columba'), written by of Adomnan of Iona in about 697, one hundred years after the death of Columba. Adomnan described the occasion when St Columba ordained Aedan mac Gabrain King of the Scots. This happened in 574, and several sons of Aedan were there. When Columba was asked which of these sons would follow his father onto the throne - would it be Artuir, or Domangart, or Eochaid Find? - the Irish saint answered, 'None of these three will be king; for they will fall in battles, slain by enemies.'

That is the first reference anywhere to a prince named Arthur (Irish, Artur or Artuir).

Adomnan added, naturally, that the Irish saint was right: Arthur and Eochaid Find were later killed in a 'battle with the Miathi' or southern Picts. The precise location of this battle can in fact be pinpointed.

The Vita Sanctae Columbae was written on the Isle of Iona, off the coast of Scotland. Columba's monastery was also the source for much of the information recorded in the Irish Annals. Monasteries kept books in which they calculated the date of Easter each year, and the monks would occasionally add snippets of information relating to the important events of that year. These were later transcribed into the various annals of the Irish Church, which took the snippets from the Easter Tables compiled on the Isle of Iona.

The Annals of Tigernach record the deaths of four sons of Aedan mac Gabrain - 'Bran & Domangart & Eochaid Find & Artur' - in a battle fought in 594 in Circenn, a Pictish province roughly contingent with modern-day Angus and Kincardineshire.

The Annals of Ulster date this same battle to 596 and mention only the deaths of Bran and Domangart. Adomman, in his 'Life of St Columba', indicated that Domangart had actually died in a separate 'battle in England'.

So - three authentic early sources, two of which mention an Arthur by name. Both tend to be completely ignored by Arthurian "experts", who simply don't want to admit that Arthur wasn't a man of southern Britain.

And then there's the poetry. Y Gododdin ('The Gododdin'), for example, is a long and bitter elegy written in honour of the British and Irish warriors who perished in a catastrophic battle. The poem was composed by Aneirin, a British poet-prince, sometime around the year 600, probably at Edinburgh (the Gododdin were the Britons of Lothian). One of the two surviving versions of Y Gododdin mentions Arthur by name (in fact, the entire poem refers to Arthur by a variety of names and descriptions).

Again, scholars have got themselves hopelessly confused over Aneirin's poem, which happens to mention Catraeth (Cad - battle; traeth - shore). The Welsh name for the North Yorkshire town of Catterick is Catraeth. So, putting two and two together - much as they have done with the two separate references to battles of 'Badon' - the experts have pronounced that Y Gododdin must be about a British disaster at a battle which never happened somewhere near Catterick. If the Angles had succeeded in wiping out the army of Lothian, they would have crowed about it. But they never even mentioned it, partly because there was no British defeat at Catterick. The poem in actuality describes Arthur's last battle - some of his friends and close relations are named, as are the landmarks which point to the precise location of the conflict, where Arthur and so many of his heroes fell.

Aneirin nods to Taliesin in his Y Gododdin poem. Taliesin is perhaps one of the most vital sources for information about Arthur, not least of all because Taliesin knew him. Arthur's name, and its variants, crops up repeatedly in Taliesin's poetry, alongside those of the other heroes who fought at the last battle and accompanied Arthur into the legends. Taliesin's surviving poems are gathered together in several Welsh manuscripts of the Middle Ages. The fact that they were transcribed - and probably 'improved' - by medieval monks does not mean that the originals weren't composed at the time of Arthur.

In his youth, Taliesin was associated with Maelgwyn of Gwynedd, who came in for ferocious criticism by St Gildas in his De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae. The Welsh Annals indicate that Maelgwyn died of the 'yellow plague' in either 547 or 549. Evidently, Gildas must have written his scathing open letter before the death of Maelgwyn. But Arthur son of Aedan - the first Arthur to appear in any historical records - was not born until 559. Doesn't that explain why Gildas failed to mention Arthur's name? And why the 'siege of Badon Hill' spoken of by Gildas had absolutely nothing whatever to do with Arthur?

Like his fellow bard Aneirin, Taliesin spent most of his life in the Old North - the region which, in current terms, encompassed northern England and much of Scotland. For that reason, as much as anything, scholars try to avoid including the poetry of Taliesin and Aneirin among the early historical sources for Arthur.

After all, we can't have anybody wondering whether Arthur might also have been based in the Old North, can we? Even though so many of the legends in their earliest forms repeatedly have Arthur going 'into the north'. No, we can't have that.

So, where does all this get us? Well, what it means is that there is a great deal more in the way of early historical source material for Arthur than most scholars are prepared to admit. And, in stark contrast to the sources that they do admit exist (and which they argue and fuss over endlessly), these other sources actually do mention Arthur. Indeed, they tell us rather a lot about him. They even allow us to reconstruct the circumstances of his last battle - fought in Angus in 594 - and to piece together a great deal more than that about his life and times.

But we do have to acknowledge that these sources exist, and that they relate to the historical Arthur (and not just to some random individual named after an earlier, more 'English' and thoroughly unidentifiable 'King Arthur'), before we can listen to what they have to say.

The majority of the self-styled Arthur "experts" don't want to listen to them, however, and so they pretend that they can't see them. They know they're there. But all the same, they don't want to look.

If they did, they might just find out who the real Arthur was.

Monday, 26 September 2011

Catraeth

There's a poem of Arthur's last battle. But, shhh-! don't tell anyone about this, because it's not very widely known.

Yes, there's an authentic, eye-witness account of that dreadful battle, composed by a man who was there. Two versions of this poem survive, one slightly longer (and probably older) than the other. It gives quite a bit of detail with regard to where the battle was fought, who was there and what happened.

It's one of the most important pieces of early British literature.

No one, it seems, has noticed that it deals with Arthur's last battle, and there are two reasons for this. They are, sadly, rather familiar reasons.

Firstly, so many scholars have refused to acknowledge any connection between Arthur and the North (Scotland, especially) that they just won't countenance the idea.

Secondly, the poem refers to a place called Catraeth.

In Welsh, Catraeth is the name of the Roman fort of Cataractonum, which became the North Yorkshire town of Catterick. So, of course, everyone assumes that the poem deals with a disastrous raid on Catterick, sometime roundabout the year 600. A British war-band left Edinburgh, went south in to the territory of the Northumbrian Angles, and came to grief. There were very few survivors.

There are problems with this analysis, though. The main one being that the Anglo-Saxons, who quickly forgot their defeats, sure liked to remember their victories. The resounding defeat of a British army of Lothian would have been remembered by the Angles, and yet with uncharacteristic reserve they chose not to mention this one.

That is not the only problem with the assumption that Aneirin's Y Gododdin poem concerned a disastrous battle at Catterick. For example, one of the British heroes mourned in the poem is 'Gereint from the south'. We know from another contemporary poem that Gereint son of Erbin from Cornwall died at another battle, which the Britons knew as Llongborth ('Harbour'). He can't have died at two different battles, can he?

The poem refers to several places which just happen to have been at or near the site of Arthur's last battle, which was nowhere near Catterick. Among those mentioned in the poem we find several names which recur side-by-side with Arthur in the early literature - Cynon, Owain, Caradog, Taliesin, etc.

Even where a part of the poem turns out to have been added in later, there is a clear link with Arthur (one extra stanza concerns a battle fought by Arthur's nephew, Domnall the Speckled, in Strathcarron in 642).

But one of the biggest problems with the notion that Y Gododdin relates a battle fought at Catterick is the fact that the poet refers to a 'tempest of pilgrims' and a 'raucous pilgrim army' which attacked the British position from the rear. There weren't any pilgrims in Anglian territory at that time.

And yet, following on from the last blogpost, we find that recurrent problem: somebody, once upon a time, said - "Oh, look! Catraeth means Catterick in Welsh. So that's where the battle happened." And it has become heresy to point out that this really doesn't make sense. After all, Catraeth probably meant 'battle-shore', so it could refer to a lot of places, especially the one where Arthur made his last stand, and this is confirmed by other references to specific places in the poem.

But because the Word of the Lord is that Catraeth is Catterick and nowhere else no one has been allowed to know that there is a contemporary poem of Arthur's last battle - a poem which tells us much about how he was betrayed, which confirms the location of the battle and indicates just how many close family members fought and died there with Arthur.

It's typical of history, or rather historians, that is. A wonderful piece of evidence, a genuine British treasure, totally misunderstood and largely ignored because one person once picked up on a coincidence (Catraeth, Catterick) and nobody since has had the imagination to ask whether there really was a battle at Catterick (evidence?), why those who fought at this battle also died somewhere else, and why the place-names mentioned in the poem don't refer to the Catterick region.

You get into trouble for raising these questions. There will be those (who probably haven't read the poem) who will scream and shout IT WAS CATTERICK because that's what they've been told.

Their loss. It's a great poem. And it helped me to reconstruct Arthur's last battle. Which did not happen at Camlan. The place is properly known as Camno.

Yes, there's an authentic, eye-witness account of that dreadful battle, composed by a man who was there. Two versions of this poem survive, one slightly longer (and probably older) than the other. It gives quite a bit of detail with regard to where the battle was fought, who was there and what happened.

It's one of the most important pieces of early British literature.

No one, it seems, has noticed that it deals with Arthur's last battle, and there are two reasons for this. They are, sadly, rather familiar reasons.

Firstly, so many scholars have refused to acknowledge any connection between Arthur and the North (Scotland, especially) that they just won't countenance the idea.

Secondly, the poem refers to a place called Catraeth.

In Welsh, Catraeth is the name of the Roman fort of Cataractonum, which became the North Yorkshire town of Catterick. So, of course, everyone assumes that the poem deals with a disastrous raid on Catterick, sometime roundabout the year 600. A British war-band left Edinburgh, went south in to the territory of the Northumbrian Angles, and came to grief. There were very few survivors.

There are problems with this analysis, though. The main one being that the Anglo-Saxons, who quickly forgot their defeats, sure liked to remember their victories. The resounding defeat of a British army of Lothian would have been remembered by the Angles, and yet with uncharacteristic reserve they chose not to mention this one.

That is not the only problem with the assumption that Aneirin's Y Gododdin poem concerned a disastrous battle at Catterick. For example, one of the British heroes mourned in the poem is 'Gereint from the south'. We know from another contemporary poem that Gereint son of Erbin from Cornwall died at another battle, which the Britons knew as Llongborth ('Harbour'). He can't have died at two different battles, can he?

The poem refers to several places which just happen to have been at or near the site of Arthur's last battle, which was nowhere near Catterick. Among those mentioned in the poem we find several names which recur side-by-side with Arthur in the early literature - Cynon, Owain, Caradog, Taliesin, etc.

Even where a part of the poem turns out to have been added in later, there is a clear link with Arthur (one extra stanza concerns a battle fought by Arthur's nephew, Domnall the Speckled, in Strathcarron in 642).

But one of the biggest problems with the notion that Y Gododdin relates a battle fought at Catterick is the fact that the poet refers to a 'tempest of pilgrims' and a 'raucous pilgrim army' which attacked the British position from the rear. There weren't any pilgrims in Anglian territory at that time.

And yet, following on from the last blogpost, we find that recurrent problem: somebody, once upon a time, said - "Oh, look! Catraeth means Catterick in Welsh. So that's where the battle happened." And it has become heresy to point out that this really doesn't make sense. After all, Catraeth probably meant 'battle-shore', so it could refer to a lot of places, especially the one where Arthur made his last stand, and this is confirmed by other references to specific places in the poem.

But because the Word of the Lord is that Catraeth is Catterick and nowhere else no one has been allowed to know that there is a contemporary poem of Arthur's last battle - a poem which tells us much about how he was betrayed, which confirms the location of the battle and indicates just how many close family members fought and died there with Arthur.

It's typical of history, or rather historians, that is. A wonderful piece of evidence, a genuine British treasure, totally misunderstood and largely ignored because one person once picked up on a coincidence (Catraeth, Catterick) and nobody since has had the imagination to ask whether there really was a battle at Catterick (evidence?), why those who fought at this battle also died somewhere else, and why the place-names mentioned in the poem don't refer to the Catterick region.

You get into trouble for raising these questions. There will be those (who probably haven't read the poem) who will scream and shout IT WAS CATTERICK because that's what they've been told.

Their loss. It's a great poem. And it helped me to reconstruct Arthur's last battle. Which did not happen at Camlan. The place is properly known as Camno.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)