I treated myself, the other day. I bought a copy of Allan Campbell McLean's The Hill of the Red Fox.

It must be 35 years since I borrowed that book from my local library in Birmingham. Time spent on holiday in Scotland had planted a deep-rooted fascination, bordering on thirst, for all things Scottish. The Hill of the Red Fox, which sits comfortably alongside Stevenson's Kidnapped and Buchan's Thirty-Nine Steps, was one of the stories which allowed me to keep in touch, as it were, with western Scotland when I was back home in the West Midlands. It also inspired my interest in the Gaelic language (there is a little glossary of Gaelic terms in the back, and this fascinated me as a kid - the Gaelic has a dignity, a romance, and a connection with nature that English seldom matches). When the chance arose, I opted to take Gaelic Studies at the University of Glasgow, largely because of the glossaries I had previously found in such books as The Hill of the Red Fox.

Rooting around a charity bookshop in Evesham, a day or two after I'd read The Hill of the Red Fox, I came across an old copy of another novel by Allan Campbell McLean. The Year of the Stranger. I'm reading it now.

Like The Hill of the Red Fox, it's set on the Isle of Skye. But whereas the former novel takes place during the Cold War 1950s and involves espionage, murder and nuclear secrets (all grist to my adolescent mill, back in the late 70s), The Year of the Stranger takes place in the Victorian era. And it paints a perfectly clear picture of the gross injustices of aristocratic rule in the Highlands and Islands.

There's a referendum coming up. The people of Scotland have a choice - do they want independence, or are they anxious to remain in the United Kingdom? I don't have a vote, although I wish I did. The vote will take place the day before my 12th wedding anniversary. I married a woman who is half-Scots. We were married on the Isle of Iona. I can think of no more exciting anniversary present than a resounding YES to Scottish independence.

There are many, many reasons why it's a good idea. Some of them are to be found in The Year of the Stranger. It's a reminder that, after the Treaty of Union between England and Scotland in 1707, the people of Scotland pretty much lost every last one of their rights. They were cleared from their native lands, forced out of their homes to make way for sheep (a lucrative business, but one that destroyed the ecology of the Highlands) or simply to provide an absentee landlord and his wealthy friends with even more empty land to call their own. Servile deference was demanded by the anglicised gentry. That deference was not just demanded - it was imposed by force. While the aristocracy turned Scotland into their own exclusive playground, those to whom the land had belonged were shipped off to America, Canada, Australia, in their thousands. Those who remained behind had no choice but to tug their forelocks and grovel to the latest outsider who called himself their landlord. A terrible punishment awaited those who resisted. The fish in the rivers belonged to the aristocracy; the deer on the hills were theirs. They owned - or believed that they owned - everything.

The spirit of the Highlanders was all but broken. Many went off to fight in Britain's wars (sustaining a disproportionate amount of casualties, compared with the rest of the UK). Those at home found themselves oppressed, not just by the aristocrats, who could buy the law, but also by religious extremists, who forced their neighbours into ever more demoralised forms of mental straitjacket. As always, aristocracy and religious zealotry went hand in hand. The once-proud people learned to live in fear of their outlandish landlords and their crazy preachers. They had become little more than slaves.

It took the 20th century to pull Scotland - and the rest of the UK - out of that moral, political and economic insanity. Votes for all, regardless of income and gender; universal education; welfare; healthcare; collective bargaining. Gradually, civilisation dawned. But all that has now been undermined.

Tom Devine, probably the most respected historian in Scotland, explained why it was time to vote YES to independence. The union was of benefit (he feels) from the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 up till the Thatcherite revolution of 1979. But that's when union with England ceased to be of any real advantage to the Scots. The neoliberal agenda being so ruthlessly pursued by successive British governments is nothing more than a determined attempt to turn back the clock. While the stark picture of gross economic, political and legal inequality as presented by Allan Campbell McLean in The Year of the Stranger strikes us today as quaintly barbaric, be in no doubt that to those who currently hold power in Westminster, that sort of rampant injustice makes perfect sense.

Social and economic progress was turned around in 1979. Margaret Thatcher's simplistic economic policies were an absolute disaster - and yet the receipts from (Scottish) North Sea Oil and Gas propped up the nation's finances, so that things didn't look quite as bad as they really were (and there was always the press to mislead us as to what was really going on). But if the natural wealth of Scotland bailed out Thatcher's failed experiments, it was the Scots who paid the greatest price - their industry practically destroyed. Nuclear weapons? The English wouldn't want them anywhere near their coastal towns. Put them within 25 miles of the most densely populated area in Scotland. Oh, and the poll tax that nobody wanted? That was visited on the Scots a full year before they tried it out in England. Scotland's wealth subsidised Westminster, but rather than show the slightest gratitude, Tory commentators chose to brand the Scots "scroungers" and "subsidy-junkies". That is what colonisation looks like.

If Scotland chooses not to free itself of the shackles of aggressive, patronising, condescending, grasping Westminster rule, it will live to regret it. Scotland is one of the richest countries in the world, and yet hundreds of thousands of its children are falling into poverty as a result of Tory ideology (there is only one - ONE - Tory MP in Scotland). A person from Aberdeenshire, when asked to explain why she is voting YES, said, "When I look out to sea, I see nothing but oil-rigs. When I look inland, I see nothing but food-banks."

And that, folks, is your warning. History is repeating itself. A corrupt and self-serving aristocracy is seeking to take us back to those dark days in which we all had to doff our caps to the idiots who lorded it over us; that, or we starved. They could take our homes, throw us out into the cold, send us overseas, deny us our rights and use lethal force against us. Their obscene wealth was stolen from the millions who actually earned it.

England can, if it chooses, wrap itself up in the Downton Abbey lies about the past and carry on down the road towards government by half-baked toffs and their vicious minions, or the only apparent alternative, which is arse-about-face UKIP-style fascism. But if the Scots want to avoid the iniquities of history being revisited upon them, they need to take the chance that is now on offer.

For one thing is clear. Those who cling to the idea of the union do so for one of two reasons.

The first is that they are the very aristocrats who believe that they own Scotland (and its people, and its natural resources) and who insist on maintaining their privileges, no matter what it takes.

The other is that they have some vague hope that somehow, the Scots and the English and the Welsh and the people of Northern Ireland will someday turn the neoliberal juggernaut around and get us back on the road to democracy and decency. But that ain't gonna happen. The English are too busy blaming everybody else in the world for their mistakes to wake up to the very real trouble they're in. The Scots are already awake. The YES campaign is by far the biggest, broadest, most inclusive and engaged grassroots campaign I've ever seen: a genuine movement of the people. It's not about nationalism. It's about reality. They know that the union is finished, and that Thatcherism killed it. They see democracy slipping ever further and further away, as the gentry comes marching back to lay claim to what it never earned. The NO campaign has behaved as the defenders of privilege always do: telling lies about what is in the people's best interests and issuing one threat after another. A conniving minority is also out there, doing the gentry's dirty work, like the hated factors of old.

There's still time to read The Year of the Stranger before the referendum. Which means there's still a chance to remind ourselves what rule by those-who-believe-they're-born-to-rule tends to mean. It wasn't always thus in the Highlands and Islands. But the Treaty of Union imposed the worst kind of patrician government-by-force on a proud and independent-minded people, and those people were worn down, beaten, cheated by magistrates, bullied by a greedy gentry and terrorised by paranoid ministers.

And that's where we're heading again, unless the Scots display their natural courage, intelligence and sense of social justice, and set themselves free. It only takes an 'X' in a box to rid the land of the fear of the landlord and his factor, and to show the world the way forward again.

Alba gu brath!!

The Future of History

Showing posts with label Iona. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Iona. Show all posts

Wednesday, 27 August 2014

Sunday, 17 August 2014

Alyth, the Scene of Arthur's Last Battle

While I work on Shakespeare's Son - my biography of Sir William Davenant, a man of whom I'm becoming increasingly fond - The Grail continues to make its way through the publishing process, courtesy of Moon Books. So, by way of a sneak preview, in this post I shall offer up some of the evidence for the location of Arthur's last battle.

The Battle of Circenn

You probably think Arthur's last battle was fought at a place called "Camlann". I've been unable to find any reference to that place-name before the Middle Ages. The very earliest mentions of anyone called Arthur in the records indicate that he died in a battle fought in Angus, Scotland.

Adomnan of Iona's Life of Columba (circa 697) tells us that Artur son of Aedan was present when his father was "ordained" king of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574. The saint predicted the fates of Aedan's sons, announcing that Artur would "fall in battle, slain by enemies". Adomnan assured his readers that this prophecy came true when Artur and at least one of his brothers was killed in a "battle of the Miathi".

The Miathi, or Maeatae, were a Pictish tribe: essentially, they held the low-lying lands to the south and east of the Highland massif. Another Latinate term for these people was Verturiones.

The Irish annals, which drew at least some of their information from the records kept by Columba's monks on the Isle of Iona, specify that Artur son of Aedan died in a "battle of Circenn". This refers to the Pictish province which was roughly contiguous with today's Angus and the Mearns. The term Circenn combined the Gaelic cir, meaning a "comb" or "crest", and cenn, "heads". Circenn, then, was the land of the Comb-heads. This tells us that the Miathi Picts modelled their appearance on their totem beast, the boar (rather like their compatriots in the Orkneys, the Orcoi, from orc - a young boar). Indeed, it is possible that the Latinate name for the Verturiones tribe combines verres and turio and indicates the "offshoots" or "offspring" of the "boar", while the very term "Pict" (variant, "Pecti", "Pecht") quite possibly derived from the Latin pecten, a "comb".

Now, let's look at "Camlann" - the traditional name for Arthur's last battle. Its first appearance in the records comes in an entry interpolated into the Welsh Annals, where it refers to a gueith cam lann or "strife of cam lann". By the time this came to be written down, the region in which Artur son of Aedan died was speaking a version of Northumbrian Old English which became the dialect known as Lowland Scots. In that dialect, cam lann would mean "comb land".

In other words, "Camlann" is merely an anglicised version of the Gaelic Circenn, the land of the "Comb-heads" in which the first Arthur on record fell in a cataclysmic battle.

Culhwch and Olwen

One of the oldest of the Welsh (i.e. British) tales to feature Arthur is that of Culhwch ac Olwen. It forms a sort of mythologised, potted account of Arthur's career, culminating in the desperate and bloody hunt for a king who - for his sins - was turned into a boar. This hunt begins with a violent amphibious landing, at a site which can be identified as Cruden Bay, on the Aberdeenshire coast, after which Arthur is met by the "saints of Ireland" who "besought his protection". The dreadful Boar-King is challenged and chased from Esgeir Oerfel, the "Cold Ridge" of the Grampians, the Boar-King making his way across country towards Llwch Tawy (Loch Tay) before he is intercepted by Arthur and his men and driven into a river.

In The King Arthur Conspiracy I identified the treacherous Boar-King as Morgan the Wealthy, a renegade British prince who abducted Arthur's wife, Gwenhwyfar, and escaped into the land of the Miathi Picts (his bolt hole appears to have been the fortified Hill of Tillymorgan in Strathbogie). The site where Morgan finally came to grief is marked by the "Morganstone" on the west bank of the River Ericht, a short distance to the west of the Hill of Alyth in the great vale of Strathmore in Angus.

Arthurian Connections with Alyth

Before we proceed, let us consider some ancient references to Arthur and his family in the context of Alyth and its immediate vicinity.

In addition to having a son named Artur or Artuir, King Aedan of the Scots had a daughter called Muirgein. According to Whitley Stokes, editing and translating the Martyrology of a 9th-century Irish monk called Oengus, Muirgein daughter of Aedan was born "in Bealach Gabrain".

The inability of certain scholars to find a "Bealach Gabrain" in Scotland has led some to argue that Muirgein daughter of Aedan was utterly unconnected with Artur son of Aedan. But place-names evolve. The Gaelic term bealach, meaning a "pass" or "gorge", usually appears as "Balloch" on today's maps. There is a "Balloch" which runs along the feet of Barry Hill and the adjacent Hill of Alyth in Strathmore.

Furthermore, this "Balloch" or bealach was in a region named after the grandfather of Artur and Muirgein. Gabran was the father of Aedan. He ruled the Scots for twenty years until his death in about AD 559 and gave his name to the region of Gowrie (a corruption of Gabran). The "Balloch" near Alyth was in Gabran's land (Gabrain) and lies close to the town of Blairgowrie, which also recalls the name of Arthur's grandfather. The "Balloch" at the foot of the Hill of Alyth was almost certainly the "Bealach Gabrain" or "pass of Gowrie" where Arthur's (half-)sister, Muirgein daughter of Aedan mac Gabrain, was born. To pretend that the Balloch of Gowrie could not have been "Bealach Gabrain" because they are not spelled the same way these days is tantamount to claiming that Londinium and London could not have been the same place.

So Arthur's sister, Muirgein (latterly, Morgan le Fay), was born near Alyth. Writing in about 1527, the Scottish historian Hector Boece also indicated that Arthur's wife was buried at Meigle, which is just a mile or two south of Alyth. Hector Boece's local tradition recalled Gwenhwyfar as Vanora (via Guanora) and claimed that she had been held hostage in the Iron Age hill-fort atop Barry Hill, adjacent to the Hill of Alyth, before she was executed and buried in what is now the kirkyard at Meigle. A carved Pictish standing stone, now on display at the Meigle museum, reputedly depicts the execution or burial of Arthur's wife.

Y Gododdin

One of the best sources of information about Arthur's last battle is the ancient epic, Y Gododdin. This was composed and sung by Aneirin, a British bard of the Old North, and can be dated to circa AD 600 (the date of Arthur's last battle is given in the Irish annals as, variously, AD 594 and 596).

Unfortunately, the relevance of Aneirin's elegiac tribute to the warriors of Lothian (the "Gododdin") has been missed by scholars who want to believe that the poem bemoans the destruction of a British war-band from the Edinburgh area which had the misfortune to be wiped out at a mythical battle fought at Catterick in North Yorkshire. No evidence exists that any such battle was fought. The Angles (forerunners of the English) preferred not to recollect their defeats but were happy to remember, and to boast about, their victories. If the Angles of Northumbria had indeed obliterated a British band of heroes from Lothian at Catterick, we might assume that they would have remembered doing so. And no scholar has yet explained the presence of "Irishman and Picts" at this imaginary battle in Anglian territory.

A verse or two of Y G[ododdin, added at a later date than the original composition, described a battle fought in Scotland (Strathcarron) in AD 642 and the death in that battle of a Scottish king who just happened to be a nephew of Artur son of Aedan. This interpolation does at least suggest that the subject of the original poem was a battle fought in roughly the same area (Scotland) by the family of Artur and his father Aedan. The Y Gododdin poem also mentions various famous warriors who appear in the early accounts of Arthur's career and who were contemporary with Artur son of Aedan.

One surviving version of Y Gododdin even mentions Artur/Artuir by name:

Gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef Arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

Confused by the misidentification of the battle sung about by Aneirin in Y Gododdin, and the assumption that Arthur himself could not have been present at that battle, scholars have persistently mistranslated this verse - mostly in an attempt to render the second half of the second line, "He was no Arthur". But Aneirin's verse should properly be translated thus:

Black ravens [warriors] sang in praise of the hero [Welsh, arwr]

of Circenn [transliterated into Welsh as "caer ceni"]. He blamed Arthur;

the dogs cursed in return for our wailing/lamentation ...

Aneirin indicated, in his Y Gododdin elegy, precisely where the final battle took place:

Eil with gwelydeint amallet

y gat veirch ae seirch greulet

bit en anysgoget bit get ...

Which translates as:

Again they came into view around the alled,

the battle-horses and the bloody armour,

still steadfast, still united ...

The "alled" was Aneirin's Welsh-language attempt at the Gaelic Allaid - also Ailt - or the Hill of Alyth.

Breuddwyd Rhonabwy

The extraordinary medieval Welsh tale of The Dream of Rhonabwy actually provides a description of the scene in the hours before Arthur's last battle was fought. The visionary seer, Rhonabwy, finds himself crossing a great plain with a river running through it (Strathmore). He is met by a character call Iddog, "Churn of Britain", who admits that it was he who caused the cataclysmic "battle of Camlan" by betraying Arthur. In company with Iddog, Rhonabwy approaches the "Ford of the Cross" (Rhyd-y-Groes) on the river. A great army is encamped on either side of the road and Arthur is seated on a little flat islet in the river, beside the ford.

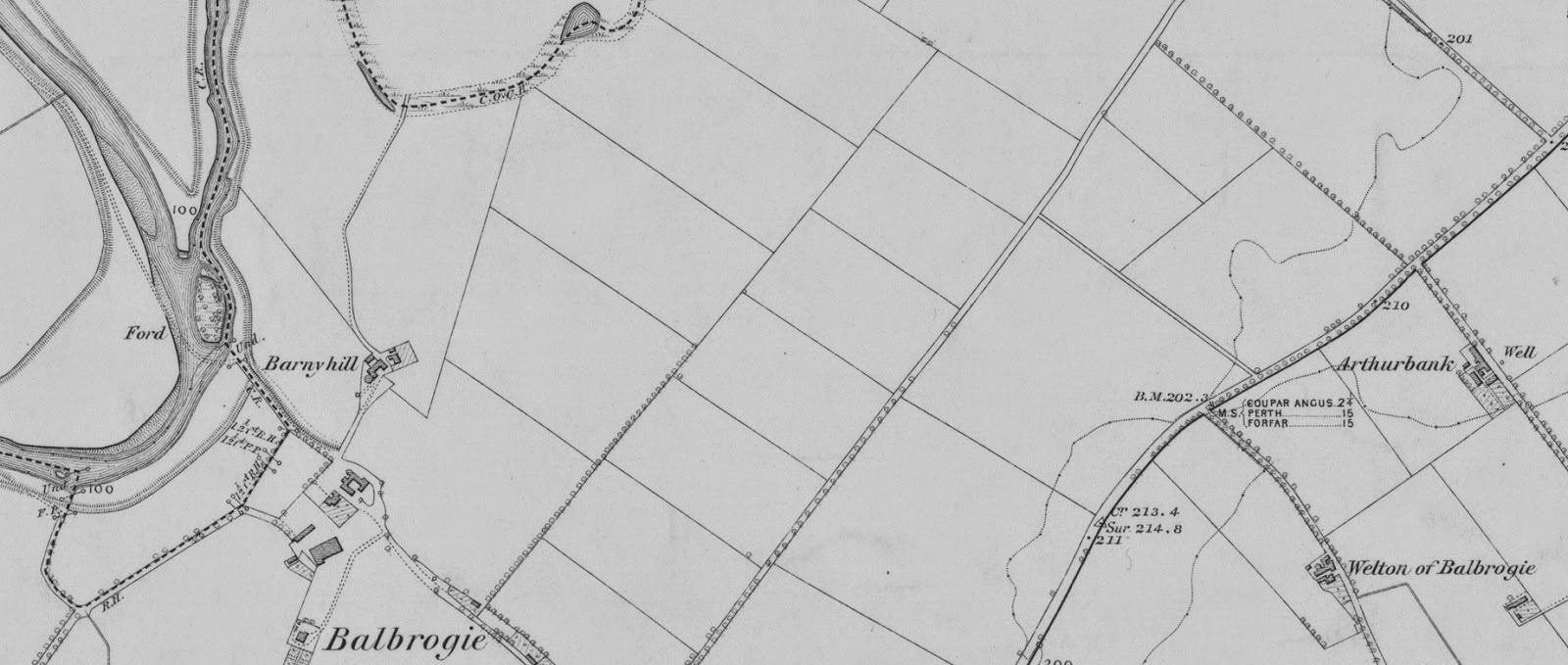

The topography precisely matches the detail from a 19th-century Ordnance Survey map of the area around Alyth seen at the top of this post. On the right-hand side of the detail is the ridge known as Arthurbank, which lies along the River Isla, opposite the junction of the River Ericht with the River Isla (a few miles down the Ericht from the site of the Morganstone). A little flat islet lies in the River Isla, close to the Arthurbank shore, and a ford runs alongside this little islet, exactly as described in the Welsh account of Rhonabwy's dream.

Aneirin also mentioned this ford in his Y Gododdin poem as rhyd benclwyd - the "ford" of the "grey" or "holy mount". There is, indeed, a Greymount marked on the map, a short distance to the north of the ford on the Isla. In his Agriculture of Perthshire, published in 1799, the Rev. Dr Robertson described the discovery of a "large Druidical temple" at Coupar Grange, adjacent to this ford. A standing stone found in this "temple" would no doubt have been rebranded a "cross" by the early Christians, so that the ford across the Isla, beside the little flat islet, would have become known as the Ford of the Cross (Rhyd-y-Groes), as described in The Dream of Rhonabwy, or the "Ford of the Grey/Holy Mount" (rhyd benclwyd) as described by Aneirin.

Until the late 18th century, an Arthurstone stood at the south-eastern edge of the Arthurbank ridge (its presence is still marked on the map). This Arthurstone corresponds to the Morganstone, a few miles away up the River Ericht, and marks the spot where Arthur fell in his battle with the Boar-King of the Miathi Picts in the land of the "crested" Comb-heads, Camlann.

The Head of the Valley of Sorrow

After the battle, Arthur's wife Gwenhwyfar was executed and buried only a mile or so away at Meigle. The legend of Culhwch and Olwen (which, interestingly, features a treacherous individual identified as Grugyn, who also appears in Aneirin's Y Gododdin) tells us that, after the battle at the river with the dangerous Boar-King, Arthur and his heroes once more "set out for the North" to overcome a fearsome witch. She was found inside a cave at Penn Nant Gofid - the "Head of the Valley of Sorrow"- on "the confines of Hell" (which we can interpret as the edge of the territory controlled by those boar-like Miathi Picts). The Welsh gofid ("sorrow/trouble/affiction/grief") appears to have been something of a pun, for another Welsh word for sorrow or grief is alaeth (compare Ailt, Allaid and Alyth, the "Head of the Valley of Alyth" being the very hill on which Arthur's wife is rumoured to have been held prisoner before her execution and burial nearby at Meigle).

In the Welsh tale, this witch is known as Orddu (that is, Gorddu - "Very Black"). A similar legend from the Isle of Mull, whose Arthurian associations have been overlooked for far too long, names the troublesome wife as Corr-dhu ("Black-Crane").

We might also note that the 9th-century Welsh monk known as Nennius described a "wonder" of Scotland in the form of "a valley in Angus, in which shouting is heard every Monday night; Glend Ailbe is its name, and it is not known who makes this noise."

Nennius's Glend Ailbe seems to be a corruption of the Gaelic word for a valley (glen) and the River Isla, or perhaps the Allaid or Hill of Alyth, which dominates the vale of Strathmore. The mysterious shouting in this "Valley of Sorrow" was reputedly heard ever Monday night. And we know from Aneirin's eye-witness account of Arthur's last battle that it came to an end on a Monday.

This is just some of the evidence for Arthur having fallen in the vicinity of Alyth. There is plenty more to come in The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - including descriptions of the Pictish symbol stones, found close to the site of that battle, which actually depict the Grail in use!

I'll let you know when the book is about to be published.

Friday, 20 December 2013

Five Facts About Arthur

Barry Hill, just north of Alyth in Angus, photographed by Richard Webb. Arthur's last battle was fought near here.

I've written quite a lot about prejudice, lately. This comes partly from my work on the final chapter for The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion, in which I analyse what makes people believe certain things - irrespective of, and often in direct contradiction of, the evidence.

Because the fact is that where a lot of history is concerned, prejudice dictates what we believe. Hence, the revelation that Arthur was Scottish (or perhaps it would be more accurate to say North British) is either ignored or derided by people who prefer to cling to the notion that he was, in some strange, anachronistic sort of way, essentially English.

A couple of posts back, I flirted with the idea of posting a handful of facts, none of which is in any way speculative, about Arthur. These indisputable facts point to one conclusion only - that the "King Arthur" we read about so often is a manufactured legend. The real Arthur was not a "king". He had no connection with southern Britain and was active somewhat later than the timeframe asserted by so many "experts".

So, here goes:

1. The earliest Arthur on record was northern.

Long before we encounter any English references to Arthur, a princely "Arthur" was written about. He was Artur mac Aedain ("Arthur son of Aedan"), whose father, Aedan mac Gabrain, was ordained as King of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574. The Life of Columba, written by Adomnan of Iona in about 697, drawing on earlier accounts written by previous abbots of Iona, suggests that Artur was present when his father Aedan was ordained. St Columba predicted that this Artur would never be king but would "fall in battle, slain by enemies". The Life of Columba goes on to confirm that Artur did indeed die in a "battle of the Miathi", the tribal name referring to the southern or Lowland Picts of central Scotland.

The Irish annals similarly indicate that Artur mac Aedain died fighting the Picts - his death in a "battle of Circenn" being dated to 594 (Annals of Tigernach). Circenn was the old Pictish province which corresponds with today's Angus and the Mearns, just north of the Tay estuary in Scotland.

Like Adomnan's Life of Columba, the Irish annals ultimately derived from the Isle of Iona, off the coast of Argyll in western Scotland. Key events were listed alongside the Easter Tables which allowed early monasteries to calculate the date of Easter each year; these events were later transcribed into the chronicles known as "annals". The source of the information regarding Artur's death in a battle against the Miathi Picts, fought in Circenn (Angus) in about 594, was therefore the monastery on Iona which had been established by St Columba - the very man who "ordained" Artur's father Aedan in 574.

Most accounts of Arthur's life avoid mentioning the Irish annals or the Life of Columba because they reveal that, long before there was any mention of Arthur in a southern or "English" context, the Irish or Scots had already established that an Arthur died fighting against the Picts in Angus. There are no surviving references to anyone named Arthur before these Irish accounts, which drew on contemporary references. Some scholars insist that Artur mac Aedain could not have been the "real" Arthur but must have been named after an earlier hero called Arthur. But the point needs to be made that no evidence whatsoever exists for anyone named Arthur before Artur mac Aedain.

2. The early British sources associate Arthur with the North.

No contemporary British accounts of Arthur survive, although we do have transcriptions of ancient poems and stories which were copied out in the Middle Ages. They all point to Arthur having been a northerner, who associated with northern princes of the late-6th century (that is, the lifetime of Artur mac Aedain).

Starting with Taliesin, who proudly called himself the "Primary Chief Bard" of Britain and who flourished in the late-6th century, we find repeated references to Arthur as a contemporary figure. For a while, at least, Taliesin was attached to the court of Urien, a king of North Rheged (Cumbria) who died in 590. By his own admission, Taliesin was also based at Edinburgh for some time. In addition to composing poems and elegies for Urien and his son Owain, Taliesin also praised Lleenog of Lennox (Loch Lomond) and his son Gwallog. He also sang a death-song for "Uthyr Pen" ("Uther the Chief") and an extraordinary account of Arthur's funeral (Preiddeu Annwn).

Equally, Aneirin - a princely bard of the North who flourished in the late-6th century - made mention of Arthur. Aneirin's masterpiece is known as Y Gododdin and sang of the warriors of Edinburgh and Lothian who perished in a military disaster fought shortly before the year 600. The earliest surviving version of Y Gododdin, written in an archaic form of Welsh, includes a direct reference to Arthur (we will return to this).

Moving onto the British stories of Arthur and his heroes, although these were transcribed by medieval monks during the Middle Ages, there is no good reason to presume that they were made up during that same period; rather, they almost certainly preserved a record which had been passed down orally by bards and storytellers. In these stories (some of which were edited and translated in the 19th century by Lady Charlotte Guest and published as the Mabinogion or "Tales of the Early Age"), Arthur is consistently presented in the company of northern individuals of the late-6th century.

Such individuals include Taliesin, Urien of North Rheged and his son Owain, Cynon son of Clydno of Edinburgh and Peredur of York (Taliesin, Owain and Cynon are among those named alongside Arthur in Aneirin's Y Gododdin poem of a northern battle fought in the late-6th century). These historical figures were later romanticised (Urien - Uriens; Owain = Yvain; Peredur = Perceval - compare Lleenog and Gwallog, who became the legendary father and son duo, Lancelot of the Lake and Galahad).

Others who appear to have accompanied Arthur on his forays "into the North" include St Cadog, one of Arthur's "four-and-twenty horsemen", who founded a monastery in central Scotland, and whose hagiography features several encounters with Arthur and other contemporary figures, such as Rhydderch of Dumbarton (died circa 614). Rhydderch, meanwhile, is repeatedly associated with the Merlin-figure, Myrddin Wyllt, who "went mad" at a battle fought in the Scottish Borders in 573 and then spent much of his time in the "Caledonian forest", where at least one of Arthur's battles was fought, according to a list compiled in about 829 by a Welsh monk commonly known as Nennius.

3. The early romances associate Arthur - and the Grail - with the North.

As early as 1120, Lambert, the canon of St Omer in Brittany, wrote of the "palace of the warrior Arthur" as being "in the land of the Picts" - or Scotland, as we would now know it. Lambert wrote in Latin, but used a Gaelic name for Arthur (Artuir militis).

Most mainstream accounts of "King Arthur" do not mention Lambert's testimony because it draws us away from the myth of the southern Arthur. That myth was forged by Geoffrey of Monmouth, whose account of Arthur's life and career formed part of his Historia Regum Britanniae or "History of the Kings of Britain", which he completed in about 1137. Geoffrey appears singlehandedly to have invented the legend of Arthur's birth at Tintagel in Cornwall. He also claimed that Merlin transported the "Giant's Dance" from Ireland by magic, bringing it to England where it became known as Stonehenge. Very few people take that claim seriously, and yet a surprising number are eager to take the equally unfounded story about Tintagel as Gospel. (In a later account, Geoffrey placed Merlin in the company of Taliesin, correctly identifying Myrddin Wyllt as the origin of the Merlin legend and a contemporary of the late-6th-century "Primary Chief Bard", but by then the damage had been done - those who wanted Arthur to have been "English" had the Tintagel myth to turn to, even though nobody before Geoffrey of Monmouth had mentioned it.)

Still, writers in Britain and on the Continent continued to link Arthur and his exploits with the North. Beroul, for example, whose verse romance of Tristan was composed in about 1200, stated unequivocally that Arthur and his Round Table were located at Stirling, on the River Forth in central Scotland. There was indeed a "Tristan" who was contemporary with Artur mac Aedain. His name was originally Pictish - Drust - but the Scots came to think of him as "St Drostan" and placed him in the company of St Columba (as "Drosten", he is named on a 9th-century Pictish stone at St Vigeans in Angus, not far from the scene of Artur's last battle; an early British account has "Drystan" fleeing with his lover, Esyllt, into the "Caledonian forest").

In Chretien de Troyes's version of the Peredur story - Perceval ou le conte du graal - the sword presented to the Grail knight by his uncle, the Fisher King, could only be "rehammered, retempered and repaired" at a lake beyond the River Forth. The Estoire del Saint Graal, composed in about 1230, stated that both Joseph of Arimathea, who supposedly brought the "Holy Grail" to Britain, and his son Josephus were buried in Scotland. At about the same time, one Guillaume le Clerc wrote his romance of Fergus, in which a young would-be knight encounters Arthur and his men in Galloway and then goes on a quest across much of Scotland. The Queste del Saint Graal (circa 1230) remarked that Celydoine, an ancestor of the knights Lancelot and Galahad, was "the first Christian king to hold sway over Scotland".

An oral tradition concerning Arthur continued in Scotland - and especially in the islands of the Hebrides - until the tales were finally written down in the 18th and 19th centuries. In one of these, which was recorded on the Isle of Tiree, very close to Iona, Arthur is "Chief Arthur son of Iuthar".

4. Arthur's enemies were northern.

Traditionally, Arthur fought against the Saxons, who colonised much of southern Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries AD. The term "Saxon" is still used in Welsh (Sais) and Scottish Gaelic (Sasunn) to designate an "Englishman" and "England" respectively. The term "England", however, derives not from the Saxons but from the Angles, who formed Engla land some time after they had established their kingdom of Northumberland.

The Angles did not lay claim to their first northern kingdom (Bryneich - or Bernicia, as the Angles called it) until about AD 547. They later added the kingdom of Deira (British Deywr) in 559, and together these adjacent territories on the coast of north-east England formed the Anglian kingdom of Northumberland. Forays were made into central Scotland (thus, Artur and his contemporaries fought them in Lennox, near Loch Lomomd, and at Craigmaddie Muir, north of Glasgow). By 590, though, an alliance of British and Irish chieftains had pretty much driven the Angles back into the sea. Only the treachery of a British petty-king, Morgan the Wealthy, whose power base was at the Edinburgh, caused the British resistance to collapse after the assassination of Urien of North Rheged.

Just five years later, the resurgent Angles overran much of the North. They finally conquered Edinburgh and Lothian in 638.

Between 590 and 595, or thereabouts, the invading "English" underwent an astonishing change of fortune - from being all-but wiped out in 590 to taking control of much of North Britain in 595.

Artur mac Aedain, we should remember, died in a battle fought in Angus in 594. During his lifetime, the Anglian threat had been contained, and almost eradicated, before an act of treachery led to the death of Arthur's companion, Urien, and then his own death opened the floodgates to the conquest of North Britain by the Angles. The historical circumstances therefore square with the later legends of Arthur: he sought to hold back the English, and was remarkably successful in doing so, until treachery struck. And with the death of Arthur, Britain was finished.

But the Angles were not his sole enemies. Geoffrey of Monmouth - who acknowledged that Arthur had fought battles around Dumbarton and Loch Lomond, a very long way from his supposed base in the south - also noted that there had been "Scots, Picts and Irish" ranged against Arthur in his final conflict, and that the various factions who had been brought into alliance by a treacherous British chieftain included both pagans and Christians. Geoffrey specifically stated that the "Saxons" were to be awarded with the land between the River Humber and Scotland - that is, Northumberland, the land of the Angles - in return for joining forces against Arthur.

5. Arthur's last battle was fought in the North.

We think of it as the "Battle of Camlann", and yet no contemporary references to any such battle survive. The last battle of Arthur doesn't appear to have been referred to as "Camlann" until the Middle Ages, when it was entered into the Annals of Wales as Gueith cam lann, the "Strife of Camlann".

It is usually assumed that "Camlann" is, and could only be, a Welsh place-name. This is not a reasonable assumption: the old Roman fort at Camelon, near Falkirk (just south of Stirling), is known as Camlan in Gaelic (Kemlin in Scots), and so we shouldn't suppose that cam lann was an authentic British (i.e. Brittonic) place-name.

In fact, the term cam lann translates via Anglo-Saxon - and via Lowland Scots, a derivative of the Old Germanic tongue spoken by the Angles, which had been established in southern Scotland by the 7th century - as "comb land".

Artur mac Aedain, we recall, died in 594 at a "battle of Circenn". The term circenn combines two Old Irish words, cir - meaning "comb" or "crest" - and cenn, meaning "heads". The Angus region, which was then known as Circenn, appears to have been the capital of the Miathi Picts, who seem to have modelled their appearance on the boar (Galam, a chief of the southern Picts who was almost certainly killed by Arthur in 580, bore two epithets: Cennaleth, or "Chief of Alyth", and Cennfaeladh, meaning "Shaved-Head"; he was also known as "Little-Boar", Welsh Baeddan, or "Little Tufted One", Gaelic Badan, since his head was shaved to represent the tuft, crest or "comb" of a boar).

So, Artur mac Aedain died in 594 in a battle in Circenn, the land of the "Comb-heads" or the boar-crested warriors of the Miathi Picts. His death more or less put an end to the British resistance to Anglian invasion.

The Arthur of legend died in a battle in "Comb land" or cam lann. His death more or less put an end to the British resistance to the "Saxons", or the English as they are now known.

With this in mind, we might return to the Y Gododdin poem of Aneirin, which sang of the heroes (many of them resident fixtures of the Arthurian legends) who fought so valiantly in a disastrous encounter with the Northumbrian Angles which took place not long before the year 600 and not all that far from Edinburgh. Indeed, Aneirin tells us where it happened:

Again they came into view around the Allaid,

The battle-horses and the bloody armour,

Still steadfast, still united ...

The "Allaid" (Gaelic Ailt) was the Hill of Alyth, above the River Isla in Strathmore, the great valley of Angus.

As previously stated, the earliest surviving version of Y Gododdin includes a reference to Arthur. This reference has been repeatedly mistranslated by scholars who do not want to think of Arthur as a northerner or to consider the possibility that Arthur might have been present at this disastrous battle between the Gododdin warriors of Lothian and the massed ranks of Angles, Scots, Irish and Picts. Here's the passage which mentions Arthur:

Gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

We can now translate this passage thus:

"Black ravens sang in praise of the hero

of Circenn. He blamed Arthur;

the dogs cursed in return for our wailing ..."

The "hero" (Welsh arwr) of "Circenn" (corrupted to caer and the genitive ceni in the transcription) was probably Arthur, who was blamed for his own death by his principle enemy whilst his black raven warriors sang their dirges over him.

As St Columba had predicted, he had "fallen in battle, slain by enemies". This battle was fought against a motley bunch of Angles, Scots, Picts and Irish, and it took place in the "comb land" (cam lann) of the "Comb-heads" (Circenn), where Arthur - surrounded by those very princes of North Britain who would follow him into the legends - was fatally wounded near the Allaid or "Hill of Alyth", the chief seat of Galam, the onetime boar-king of the Miathi.

This region is also known as Gowrie, after Gabran, the grandfather of Artur mac Aedain, who had annexed the territory in about 525. The place where Artur fell is known to this day as Arthurbank, the precise spot still being known as Arthurstone.

Southern Britain never had an Arthur, nor even a figure remotely like Artur mac Aedain.

The myth of the southern Arthur is exactly that - a myth.

The real Arthur, as all the available evidence indicates, was a northerner, active in the second half of the 6th century, and only blind prejudice stands in the way of our recognition of Artur mac Aedain as the hero he was.

I've written quite a lot about prejudice, lately. This comes partly from my work on the final chapter for The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion, in which I analyse what makes people believe certain things - irrespective of, and often in direct contradiction of, the evidence.

Because the fact is that where a lot of history is concerned, prejudice dictates what we believe. Hence, the revelation that Arthur was Scottish (or perhaps it would be more accurate to say North British) is either ignored or derided by people who prefer to cling to the notion that he was, in some strange, anachronistic sort of way, essentially English.

A couple of posts back, I flirted with the idea of posting a handful of facts, none of which is in any way speculative, about Arthur. These indisputable facts point to one conclusion only - that the "King Arthur" we read about so often is a manufactured legend. The real Arthur was not a "king". He had no connection with southern Britain and was active somewhat later than the timeframe asserted by so many "experts".

So, here goes:

1. The earliest Arthur on record was northern.

Long before we encounter any English references to Arthur, a princely "Arthur" was written about. He was Artur mac Aedain ("Arthur son of Aedan"), whose father, Aedan mac Gabrain, was ordained as King of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574. The Life of Columba, written by Adomnan of Iona in about 697, drawing on earlier accounts written by previous abbots of Iona, suggests that Artur was present when his father Aedan was ordained. St Columba predicted that this Artur would never be king but would "fall in battle, slain by enemies". The Life of Columba goes on to confirm that Artur did indeed die in a "battle of the Miathi", the tribal name referring to the southern or Lowland Picts of central Scotland.

The Irish annals similarly indicate that Artur mac Aedain died fighting the Picts - his death in a "battle of Circenn" being dated to 594 (Annals of Tigernach). Circenn was the old Pictish province which corresponds with today's Angus and the Mearns, just north of the Tay estuary in Scotland.

Like Adomnan's Life of Columba, the Irish annals ultimately derived from the Isle of Iona, off the coast of Argyll in western Scotland. Key events were listed alongside the Easter Tables which allowed early monasteries to calculate the date of Easter each year; these events were later transcribed into the chronicles known as "annals". The source of the information regarding Artur's death in a battle against the Miathi Picts, fought in Circenn (Angus) in about 594, was therefore the monastery on Iona which had been established by St Columba - the very man who "ordained" Artur's father Aedan in 574.

Most accounts of Arthur's life avoid mentioning the Irish annals or the Life of Columba because they reveal that, long before there was any mention of Arthur in a southern or "English" context, the Irish or Scots had already established that an Arthur died fighting against the Picts in Angus. There are no surviving references to anyone named Arthur before these Irish accounts, which drew on contemporary references. Some scholars insist that Artur mac Aedain could not have been the "real" Arthur but must have been named after an earlier hero called Arthur. But the point needs to be made that no evidence whatsoever exists for anyone named Arthur before Artur mac Aedain.

2. The early British sources associate Arthur with the North.

No contemporary British accounts of Arthur survive, although we do have transcriptions of ancient poems and stories which were copied out in the Middle Ages. They all point to Arthur having been a northerner, who associated with northern princes of the late-6th century (that is, the lifetime of Artur mac Aedain).

Starting with Taliesin, who proudly called himself the "Primary Chief Bard" of Britain and who flourished in the late-6th century, we find repeated references to Arthur as a contemporary figure. For a while, at least, Taliesin was attached to the court of Urien, a king of North Rheged (Cumbria) who died in 590. By his own admission, Taliesin was also based at Edinburgh for some time. In addition to composing poems and elegies for Urien and his son Owain, Taliesin also praised Lleenog of Lennox (Loch Lomond) and his son Gwallog. He also sang a death-song for "Uthyr Pen" ("Uther the Chief") and an extraordinary account of Arthur's funeral (Preiddeu Annwn).

Equally, Aneirin - a princely bard of the North who flourished in the late-6th century - made mention of Arthur. Aneirin's masterpiece is known as Y Gododdin and sang of the warriors of Edinburgh and Lothian who perished in a military disaster fought shortly before the year 600. The earliest surviving version of Y Gododdin, written in an archaic form of Welsh, includes a direct reference to Arthur (we will return to this).

Moving onto the British stories of Arthur and his heroes, although these were transcribed by medieval monks during the Middle Ages, there is no good reason to presume that they were made up during that same period; rather, they almost certainly preserved a record which had been passed down orally by bards and storytellers. In these stories (some of which were edited and translated in the 19th century by Lady Charlotte Guest and published as the Mabinogion or "Tales of the Early Age"), Arthur is consistently presented in the company of northern individuals of the late-6th century.

Such individuals include Taliesin, Urien of North Rheged and his son Owain, Cynon son of Clydno of Edinburgh and Peredur of York (Taliesin, Owain and Cynon are among those named alongside Arthur in Aneirin's Y Gododdin poem of a northern battle fought in the late-6th century). These historical figures were later romanticised (Urien - Uriens; Owain = Yvain; Peredur = Perceval - compare Lleenog and Gwallog, who became the legendary father and son duo, Lancelot of the Lake and Galahad).

Others who appear to have accompanied Arthur on his forays "into the North" include St Cadog, one of Arthur's "four-and-twenty horsemen", who founded a monastery in central Scotland, and whose hagiography features several encounters with Arthur and other contemporary figures, such as Rhydderch of Dumbarton (died circa 614). Rhydderch, meanwhile, is repeatedly associated with the Merlin-figure, Myrddin Wyllt, who "went mad" at a battle fought in the Scottish Borders in 573 and then spent much of his time in the "Caledonian forest", where at least one of Arthur's battles was fought, according to a list compiled in about 829 by a Welsh monk commonly known as Nennius.

3. The early romances associate Arthur - and the Grail - with the North.

As early as 1120, Lambert, the canon of St Omer in Brittany, wrote of the "palace of the warrior Arthur" as being "in the land of the Picts" - or Scotland, as we would now know it. Lambert wrote in Latin, but used a Gaelic name for Arthur (Artuir militis).

Most mainstream accounts of "King Arthur" do not mention Lambert's testimony because it draws us away from the myth of the southern Arthur. That myth was forged by Geoffrey of Monmouth, whose account of Arthur's life and career formed part of his Historia Regum Britanniae or "History of the Kings of Britain", which he completed in about 1137. Geoffrey appears singlehandedly to have invented the legend of Arthur's birth at Tintagel in Cornwall. He also claimed that Merlin transported the "Giant's Dance" from Ireland by magic, bringing it to England where it became known as Stonehenge. Very few people take that claim seriously, and yet a surprising number are eager to take the equally unfounded story about Tintagel as Gospel. (In a later account, Geoffrey placed Merlin in the company of Taliesin, correctly identifying Myrddin Wyllt as the origin of the Merlin legend and a contemporary of the late-6th-century "Primary Chief Bard", but by then the damage had been done - those who wanted Arthur to have been "English" had the Tintagel myth to turn to, even though nobody before Geoffrey of Monmouth had mentioned it.)

Still, writers in Britain and on the Continent continued to link Arthur and his exploits with the North. Beroul, for example, whose verse romance of Tristan was composed in about 1200, stated unequivocally that Arthur and his Round Table were located at Stirling, on the River Forth in central Scotland. There was indeed a "Tristan" who was contemporary with Artur mac Aedain. His name was originally Pictish - Drust - but the Scots came to think of him as "St Drostan" and placed him in the company of St Columba (as "Drosten", he is named on a 9th-century Pictish stone at St Vigeans in Angus, not far from the scene of Artur's last battle; an early British account has "Drystan" fleeing with his lover, Esyllt, into the "Caledonian forest").

In Chretien de Troyes's version of the Peredur story - Perceval ou le conte du graal - the sword presented to the Grail knight by his uncle, the Fisher King, could only be "rehammered, retempered and repaired" at a lake beyond the River Forth. The Estoire del Saint Graal, composed in about 1230, stated that both Joseph of Arimathea, who supposedly brought the "Holy Grail" to Britain, and his son Josephus were buried in Scotland. At about the same time, one Guillaume le Clerc wrote his romance of Fergus, in which a young would-be knight encounters Arthur and his men in Galloway and then goes on a quest across much of Scotland. The Queste del Saint Graal (circa 1230) remarked that Celydoine, an ancestor of the knights Lancelot and Galahad, was "the first Christian king to hold sway over Scotland".

An oral tradition concerning Arthur continued in Scotland - and especially in the islands of the Hebrides - until the tales were finally written down in the 18th and 19th centuries. In one of these, which was recorded on the Isle of Tiree, very close to Iona, Arthur is "Chief Arthur son of Iuthar".

4. Arthur's enemies were northern.

Traditionally, Arthur fought against the Saxons, who colonised much of southern Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries AD. The term "Saxon" is still used in Welsh (Sais) and Scottish Gaelic (Sasunn) to designate an "Englishman" and "England" respectively. The term "England", however, derives not from the Saxons but from the Angles, who formed Engla land some time after they had established their kingdom of Northumberland.

The Angles did not lay claim to their first northern kingdom (Bryneich - or Bernicia, as the Angles called it) until about AD 547. They later added the kingdom of Deira (British Deywr) in 559, and together these adjacent territories on the coast of north-east England formed the Anglian kingdom of Northumberland. Forays were made into central Scotland (thus, Artur and his contemporaries fought them in Lennox, near Loch Lomomd, and at Craigmaddie Muir, north of Glasgow). By 590, though, an alliance of British and Irish chieftains had pretty much driven the Angles back into the sea. Only the treachery of a British petty-king, Morgan the Wealthy, whose power base was at the Edinburgh, caused the British resistance to collapse after the assassination of Urien of North Rheged.

Just five years later, the resurgent Angles overran much of the North. They finally conquered Edinburgh and Lothian in 638.

Between 590 and 595, or thereabouts, the invading "English" underwent an astonishing change of fortune - from being all-but wiped out in 590 to taking control of much of North Britain in 595.

Artur mac Aedain, we should remember, died in a battle fought in Angus in 594. During his lifetime, the Anglian threat had been contained, and almost eradicated, before an act of treachery led to the death of Arthur's companion, Urien, and then his own death opened the floodgates to the conquest of North Britain by the Angles. The historical circumstances therefore square with the later legends of Arthur: he sought to hold back the English, and was remarkably successful in doing so, until treachery struck. And with the death of Arthur, Britain was finished.

But the Angles were not his sole enemies. Geoffrey of Monmouth - who acknowledged that Arthur had fought battles around Dumbarton and Loch Lomond, a very long way from his supposed base in the south - also noted that there had been "Scots, Picts and Irish" ranged against Arthur in his final conflict, and that the various factions who had been brought into alliance by a treacherous British chieftain included both pagans and Christians. Geoffrey specifically stated that the "Saxons" were to be awarded with the land between the River Humber and Scotland - that is, Northumberland, the land of the Angles - in return for joining forces against Arthur.

5. Arthur's last battle was fought in the North.

We think of it as the "Battle of Camlann", and yet no contemporary references to any such battle survive. The last battle of Arthur doesn't appear to have been referred to as "Camlann" until the Middle Ages, when it was entered into the Annals of Wales as Gueith cam lann, the "Strife of Camlann".

It is usually assumed that "Camlann" is, and could only be, a Welsh place-name. This is not a reasonable assumption: the old Roman fort at Camelon, near Falkirk (just south of Stirling), is known as Camlan in Gaelic (Kemlin in Scots), and so we shouldn't suppose that cam lann was an authentic British (i.e. Brittonic) place-name.

In fact, the term cam lann translates via Anglo-Saxon - and via Lowland Scots, a derivative of the Old Germanic tongue spoken by the Angles, which had been established in southern Scotland by the 7th century - as "comb land".

Artur mac Aedain, we recall, died in 594 at a "battle of Circenn". The term circenn combines two Old Irish words, cir - meaning "comb" or "crest" - and cenn, meaning "heads". The Angus region, which was then known as Circenn, appears to have been the capital of the Miathi Picts, who seem to have modelled their appearance on the boar (Galam, a chief of the southern Picts who was almost certainly killed by Arthur in 580, bore two epithets: Cennaleth, or "Chief of Alyth", and Cennfaeladh, meaning "Shaved-Head"; he was also known as "Little-Boar", Welsh Baeddan, or "Little Tufted One", Gaelic Badan, since his head was shaved to represent the tuft, crest or "comb" of a boar).

So, Artur mac Aedain died in 594 in a battle in Circenn, the land of the "Comb-heads" or the boar-crested warriors of the Miathi Picts. His death more or less put an end to the British resistance to Anglian invasion.

The Arthur of legend died in a battle in "Comb land" or cam lann. His death more or less put an end to the British resistance to the "Saxons", or the English as they are now known.

With this in mind, we might return to the Y Gododdin poem of Aneirin, which sang of the heroes (many of them resident fixtures of the Arthurian legends) who fought so valiantly in a disastrous encounter with the Northumbrian Angles which took place not long before the year 600 and not all that far from Edinburgh. Indeed, Aneirin tells us where it happened:

Again they came into view around the Allaid,

The battle-horses and the bloody armour,

Still steadfast, still united ...

The "Allaid" (Gaelic Ailt) was the Hill of Alyth, above the River Isla in Strathmore, the great valley of Angus.

As previously stated, the earliest surviving version of Y Gododdin includes a reference to Arthur. This reference has been repeatedly mistranslated by scholars who do not want to think of Arthur as a northerner or to consider the possibility that Arthur might have been present at this disastrous battle between the Gododdin warriors of Lothian and the massed ranks of Angles, Scots, Irish and Picts. Here's the passage which mentions Arthur:

Gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

We can now translate this passage thus:

"Black ravens sang in praise of the hero

of Circenn. He blamed Arthur;

the dogs cursed in return for our wailing ..."

The "hero" (Welsh arwr) of "Circenn" (corrupted to caer and the genitive ceni in the transcription) was probably Arthur, who was blamed for his own death by his principle enemy whilst his black raven warriors sang their dirges over him.

As St Columba had predicted, he had "fallen in battle, slain by enemies". This battle was fought against a motley bunch of Angles, Scots, Picts and Irish, and it took place in the "comb land" (cam lann) of the "Comb-heads" (Circenn), where Arthur - surrounded by those very princes of North Britain who would follow him into the legends - was fatally wounded near the Allaid or "Hill of Alyth", the chief seat of Galam, the onetime boar-king of the Miathi.

This region is also known as Gowrie, after Gabran, the grandfather of Artur mac Aedain, who had annexed the territory in about 525. The place where Artur fell is known to this day as Arthurbank, the precise spot still being known as Arthurstone.

Southern Britain never had an Arthur, nor even a figure remotely like Artur mac Aedain.

The myth of the southern Arthur is exactly that - a myth.

The real Arthur, as all the available evidence indicates, was a northerner, active in the second half of the 6th century, and only blind prejudice stands in the way of our recognition of Artur mac Aedain as the hero he was.

Tuesday, 17 December 2013

Finding Arthur

Very exciting to see this in the Scotsman newspaper yesterday. It's a short piece about Adam Ardrey's latest Arthurian publication, Finding Arthur: The Truth Behind the Legend of the Once and Future King.

I've had some contact with Adam Ardrey in recent years - although, keen as I am to preserve my historiographical independence, we've not exactly compared notes. I read his Finding Merlin when it came out in 2007, and we've communicated once or twice since then. But we're hardly collaborators.

I stress that for a couple of reasons. First, let me quote Ardrey's words from the back cover of Finding Merlin:

"If I am right, it would appear that, for 1,500 years, those with the power to do so have presented a history that, literally, suited their book, irrespective of its divergence from the evidence, and that the stories of Arthur and Merlin which form the British foundation myth are almost entirely pieces of propaganda based on various biases. If I am right, British history for the period from the late fifth to the early seventh century stands to be rewritten."

Sounds a bit like me, doesn't it? I too have argued that propaganda and bias have dictated the retelling of the Arthurian legends through the ages - just as propaganda and bias dictate what we allowed to hear, think and believe about William Shakespeare.

What is more, though, Adam Ardrey argues in his Finding Arthur book, not only that Artur mac Aedain was the original Arthur, but that he was buried on the Isle of Iona.

So we agree on that, too.

In other words, both of us have - independently - identified a known historical prince as the original "King Arthur", and we have both tracked down his grave to the sacred royal burial isle of the Scottish kings. That's two intelligent and inquisitive individuals who have each devoted years to the subject arriving at very similar conclusions.

I posted the piece in the Scotsman newspaper (link above) to Facebook yesterday, and it was quickly shared by a very successful historical novelist. The responses were most telling.

First came the observation that a Scottish historian had received coverage in a Scottish newspaper for his theory that Arthur was Scottish. Evidently, this was all very suspicious (I pointed out that I'm an English historian with Welsh roots, and so the suggestion that only a Scot would think Arthur might have been Scottish doesn't quite stand up). What makes this kneejerk rush to judgement so interesting is that there is no basis for it. It is, in fact, a form of projection. The fact that there is no evidence whatsoever that Arthur was what the English like to think he was gets instantly spun round, becoming no other culture is allowed to claim Arthur as its own, regardless of the evidence.

I posted a few days ago about the Ossian poems, translated from the Gaelic and published by James Macpherson in the 1760s, and the English response to the evidence of a thriving, heroic Gaelic culture at a time when England didn't even exist. The response was nothing short of blind fury - a kind of spluttering outrage that the "primitives" and "savages" of the Highlands and Islands should presume to imagine that they had any pedigree, any marvellous history, for such cultural treasures belonged only to the English!!!

The same prejudice shows itself whenever the Scottish Arthur is mentioned. Without viewing the evidence, the instinctive response is: "No, he can't have been." I repeat - without viewing the evidence. So we are not dealing with considered judgements here. We are dealing with prejudice, pure and simple. The implicit racism is apparent in the suggestion that only a Scottish historian would try to place Arthur in Scotland. Even though the very first Arthur to appear in any historical record was a Scot!

There is, then, a wall of prejudice encountered by anyone who, having spent years studying and researching the evidence, concludes that there was only one viable candidate for the prestigious role of the original Arthur - and it was Artur mac Aedain, whose father was ordained as the King of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574.

It is reassuring, then, to find that others who have devoted themselves to uncovering the historical truth behind the Arthur legend have arrived at much the same conclusion as me - he was Artur mac Aedain, and he was buried on Iona. The question, then, is when will the tide turn? When will the wall of prejudice crumble in the face of the evidence? When will the English finally admit that they have no claim at all to Arthur?

(I don't include the Welsh here because Arthur was British, and Welsh-speaking Britain extended at least as far north as the River Forth in his day; there are no grounds for presuming that, if Arthur was the son of a Scottish king, then he couldn't have been Welsh: rather, that argument is based on a misunderstanding of the geopolitics of 6th-century Britain.)

I'm tempted to post, over the next few days, a number of indisputable facts about Arthur. These are not assumptions, but genuine facts. And they all point in one direction, and one direction only.

The English might fight tooth and nail to cling to their myth of King Arthur. But there can be no reasonable doubt as to who the original Arthur was.

Unless you're determined to ignore the evidence, that is.

I've had some contact with Adam Ardrey in recent years - although, keen as I am to preserve my historiographical independence, we've not exactly compared notes. I read his Finding Merlin when it came out in 2007, and we've communicated once or twice since then. But we're hardly collaborators.

I stress that for a couple of reasons. First, let me quote Ardrey's words from the back cover of Finding Merlin:

"If I am right, it would appear that, for 1,500 years, those with the power to do so have presented a history that, literally, suited their book, irrespective of its divergence from the evidence, and that the stories of Arthur and Merlin which form the British foundation myth are almost entirely pieces of propaganda based on various biases. If I am right, British history for the period from the late fifth to the early seventh century stands to be rewritten."

Sounds a bit like me, doesn't it? I too have argued that propaganda and bias have dictated the retelling of the Arthurian legends through the ages - just as propaganda and bias dictate what we allowed to hear, think and believe about William Shakespeare.

What is more, though, Adam Ardrey argues in his Finding Arthur book, not only that Artur mac Aedain was the original Arthur, but that he was buried on the Isle of Iona.

So we agree on that, too.

In other words, both of us have - independently - identified a known historical prince as the original "King Arthur", and we have both tracked down his grave to the sacred royal burial isle of the Scottish kings. That's two intelligent and inquisitive individuals who have each devoted years to the subject arriving at very similar conclusions.

I posted the piece in the Scotsman newspaper (link above) to Facebook yesterday, and it was quickly shared by a very successful historical novelist. The responses were most telling.

First came the observation that a Scottish historian had received coverage in a Scottish newspaper for his theory that Arthur was Scottish. Evidently, this was all very suspicious (I pointed out that I'm an English historian with Welsh roots, and so the suggestion that only a Scot would think Arthur might have been Scottish doesn't quite stand up). What makes this kneejerk rush to judgement so interesting is that there is no basis for it. It is, in fact, a form of projection. The fact that there is no evidence whatsoever that Arthur was what the English like to think he was gets instantly spun round, becoming no other culture is allowed to claim Arthur as its own, regardless of the evidence.

I posted a few days ago about the Ossian poems, translated from the Gaelic and published by James Macpherson in the 1760s, and the English response to the evidence of a thriving, heroic Gaelic culture at a time when England didn't even exist. The response was nothing short of blind fury - a kind of spluttering outrage that the "primitives" and "savages" of the Highlands and Islands should presume to imagine that they had any pedigree, any marvellous history, for such cultural treasures belonged only to the English!!!

The same prejudice shows itself whenever the Scottish Arthur is mentioned. Without viewing the evidence, the instinctive response is: "No, he can't have been." I repeat - without viewing the evidence. So we are not dealing with considered judgements here. We are dealing with prejudice, pure and simple. The implicit racism is apparent in the suggestion that only a Scottish historian would try to place Arthur in Scotland. Even though the very first Arthur to appear in any historical record was a Scot!

There is, then, a wall of prejudice encountered by anyone who, having spent years studying and researching the evidence, concludes that there was only one viable candidate for the prestigious role of the original Arthur - and it was Artur mac Aedain, whose father was ordained as the King of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574.

It is reassuring, then, to find that others who have devoted themselves to uncovering the historical truth behind the Arthur legend have arrived at much the same conclusion as me - he was Artur mac Aedain, and he was buried on Iona. The question, then, is when will the tide turn? When will the wall of prejudice crumble in the face of the evidence? When will the English finally admit that they have no claim at all to Arthur?

(I don't include the Welsh here because Arthur was British, and Welsh-speaking Britain extended at least as far north as the River Forth in his day; there are no grounds for presuming that, if Arthur was the son of a Scottish king, then he couldn't have been Welsh: rather, that argument is based on a misunderstanding of the geopolitics of 6th-century Britain.)

I'm tempted to post, over the next few days, a number of indisputable facts about Arthur. These are not assumptions, but genuine facts. And they all point in one direction, and one direction only.

The English might fight tooth and nail to cling to their myth of King Arthur. But there can be no reasonable doubt as to who the original Arthur was.

Unless you're determined to ignore the evidence, that is.

Labels:

Arthur,

Arthur's Grave,

Iona,

Merlin,

Ossian,

Scotland,

Shakespeare,

St Columba

Thursday, 15 August 2013

Macbeth Died Today

He wasn't as bad as he's made out to be.

In fact, Macbethad son of Findlaech was one of Scotland's most successful kings. He reigned for 17 years and was the first Scottish king to undertake a pilgrimage to Rome, 'scattering money like seed' on the way, which can only have meant that his kingdom was safe enough for him to absent himself from it for two years.

He did not murder his predecessor, King Duncan, in a treacherous bedroom incident. Duncan was a useless king, defeated by Macbeth in open battle.

Seventeen years later, on 15 August 1057, Duncan's son Malcolm slew Macbeth in the battle of Lumphanan in Mar. The 'Red King', as the Prophecy of Berchan described him, was buried on the Isle of Iona - or, as Shakespeare put it:

'Carried to Colmekill,

The sacred storehouse of his predecessors,

And guardian of their bones.'

The Prophecy of Berchan offers a wholly different view of Macbeth from the one we're used to:

The Red King will take the kingdom ... the ruddy-faced, yellow-haired, tall one, I shall be joyful in him. Scotland will be brimful, in the west and in the east, during the reign of the furious Red One.

Which raises the question, why do we imagine him to have been a murderous tyrant?

Fiona Watson, in her 'True History' of Macbeth, suggests that it started with the Church. For reasons to do with establishing the right of succession, the medieval Church chose to blacken Macbeth's name (it wouldn't be the first time, or the last, the Church rewrite history to suit its agenda). But the blame should also lie at Shakespeare's door.

Although ... Shakespeare seldom, if ever, wrote history as History. Take his famous portrayal of Richard III: it's hardly accurate, in strictly historical terms, but it served the purposes of Tudor propaganda, because in order to strengthen their rather dubious claim to the throne, the Tudors (Henry VII through Elizabeth I) found it expedient to misrepresent King Richard as a deformed monster.

If anything, though, Shakespeare's Richard 'Crookback' is more a portrait of Sir Robert Cecil, second son of William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, Lord Treasurer, chief minister and most trusted advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. Robert Cecil matched Shakespeare's depiction of Richard III to a tee - he was stunted, dwarfish, hunchbacked and splay-footed:

Backed like a lute case,

Bellied like a drum,

Like jackanapes on horseback

Sits little Robin Thumb

in the words of a popular rhyme of the day.

Cecil also conformed to Shakespeare's presentation of Richard III's personality - feverishly industrious, devilishly devious, two-faced and dangerous, the younger Cecil fitted the description. He was groomed by his father to take over as Elizabeth's most trusted secretary, and her successor became utterly dependent on him, much to the nation's distress.

That successor was, of course, King James VI of Scotland, who liked to trace his ancestry back to Macbeth's legendary companion, Banquo.

Shakespeare, however, recognised him as a true 'son' (Gaelic mac) of [Eliza]beth. He was every bit as unprincipled and intolerant as Elizabeth had been, and after appealing to James's conscience in several pointed plays (Hamlet through to Othello), Shakespeare finally gave up on the Scottish monarch.

The last straw was the execution of Father Henry Garnet, superior of the Society of Jesus in England, in the wake of the Gunpowder Plot. Shakespeare took this as the inspiration for the opening scenes of his Tragedy of Macbeth, with the saintly Garnet taking the role of King Duncan and James himself characterised as the once-noble Macbeth ('Son of Beth'), whose lust for power turned him into a 'bloody tyrant', a 'butcher' with 'hangman's hands'.

So Shakespeare's portrait of Macbeth had little to do with the original - who died on this day 956 years ago - and much to do with the reigning king, James I of England and VI of Scotland.

Time, you might say, for Macbeth to be rehabilitated - like King Richard III, in fact, who wasn't that bad either.

And while we're at it, maybe we should acknowledge that Shakespeare's historical characters weren't necessarily based on the originals, but on the dangerous, treacherous, self-serving and deceitful men of power of his own day.

(Plenty more on this, folks, in Who Killed William Shakespeare - get hold of your copy now, before everyone jumps on the bandwagon!!)

In fact, Macbethad son of Findlaech was one of Scotland's most successful kings. He reigned for 17 years and was the first Scottish king to undertake a pilgrimage to Rome, 'scattering money like seed' on the way, which can only have meant that his kingdom was safe enough for him to absent himself from it for two years.

He did not murder his predecessor, King Duncan, in a treacherous bedroom incident. Duncan was a useless king, defeated by Macbeth in open battle.

Seventeen years later, on 15 August 1057, Duncan's son Malcolm slew Macbeth in the battle of Lumphanan in Mar. The 'Red King', as the Prophecy of Berchan described him, was buried on the Isle of Iona - or, as Shakespeare put it:

'Carried to Colmekill,

The sacred storehouse of his predecessors,

And guardian of their bones.'

The Prophecy of Berchan offers a wholly different view of Macbeth from the one we're used to:

The Red King will take the kingdom ... the ruddy-faced, yellow-haired, tall one, I shall be joyful in him. Scotland will be brimful, in the west and in the east, during the reign of the furious Red One.

Which raises the question, why do we imagine him to have been a murderous tyrant?

Fiona Watson, in her 'True History' of Macbeth, suggests that it started with the Church. For reasons to do with establishing the right of succession, the medieval Church chose to blacken Macbeth's name (it wouldn't be the first time, or the last, the Church rewrite history to suit its agenda). But the blame should also lie at Shakespeare's door.

Although ... Shakespeare seldom, if ever, wrote history as History. Take his famous portrayal of Richard III: it's hardly accurate, in strictly historical terms, but it served the purposes of Tudor propaganda, because in order to strengthen their rather dubious claim to the throne, the Tudors (Henry VII through Elizabeth I) found it expedient to misrepresent King Richard as a deformed monster.

If anything, though, Shakespeare's Richard 'Crookback' is more a portrait of Sir Robert Cecil, second son of William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, Lord Treasurer, chief minister and most trusted advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. Robert Cecil matched Shakespeare's depiction of Richard III to a tee - he was stunted, dwarfish, hunchbacked and splay-footed:

Backed like a lute case,

Bellied like a drum,

Like jackanapes on horseback

Sits little Robin Thumb

in the words of a popular rhyme of the day.

Cecil also conformed to Shakespeare's presentation of Richard III's personality - feverishly industrious, devilishly devious, two-faced and dangerous, the younger Cecil fitted the description. He was groomed by his father to take over as Elizabeth's most trusted secretary, and her successor became utterly dependent on him, much to the nation's distress.

That successor was, of course, King James VI of Scotland, who liked to trace his ancestry back to Macbeth's legendary companion, Banquo.

Shakespeare, however, recognised him as a true 'son' (Gaelic mac) of [Eliza]beth. He was every bit as unprincipled and intolerant as Elizabeth had been, and after appealing to James's conscience in several pointed plays (Hamlet through to Othello), Shakespeare finally gave up on the Scottish monarch.

The last straw was the execution of Father Henry Garnet, superior of the Society of Jesus in England, in the wake of the Gunpowder Plot. Shakespeare took this as the inspiration for the opening scenes of his Tragedy of Macbeth, with the saintly Garnet taking the role of King Duncan and James himself characterised as the once-noble Macbeth ('Son of Beth'), whose lust for power turned him into a 'bloody tyrant', a 'butcher' with 'hangman's hands'.

So Shakespeare's portrait of Macbeth had little to do with the original - who died on this day 956 years ago - and much to do with the reigning king, James I of England and VI of Scotland.

Time, you might say, for Macbeth to be rehabilitated - like King Richard III, in fact, who wasn't that bad either.

And while we're at it, maybe we should acknowledge that Shakespeare's historical characters weren't necessarily based on the originals, but on the dangerous, treacherous, self-serving and deceitful men of power of his own day.

(Plenty more on this, folks, in Who Killed William Shakespeare - get hold of your copy now, before everyone jumps on the bandwagon!!)

Friday, 17 May 2013

Breaking News

A headline in The Scotsman newspaper:

"ISLE OF IONA MAY BE ANCIENT BURIAL SITE"

Now, if I were a cynic I would tempted to respond with a headline of my own. Something like:

"WESTMINSTER ABBEY MIGHT BE A CHURCH"

But I'm not a cynic - no, really I'm not - so I won't.

The news piece in The Scotsman announces that two geophysical surveys have been carried out on the east side of the Isle of Iona (for the sake of reference, Iona is about one mile across). These surveys have identified burial sites near the site of the present village hall and beside Martyr's Bay (where the photo, above, was taken).