The Future of History

Showing posts with label Gwenhwyfar. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Gwenhwyfar. Show all posts

Sunday, 17 August 2014

Alyth, the Scene of Arthur's Last Battle

While I work on Shakespeare's Son - my biography of Sir William Davenant, a man of whom I'm becoming increasingly fond - The Grail continues to make its way through the publishing process, courtesy of Moon Books. So, by way of a sneak preview, in this post I shall offer up some of the evidence for the location of Arthur's last battle.

The Battle of Circenn

You probably think Arthur's last battle was fought at a place called "Camlann". I've been unable to find any reference to that place-name before the Middle Ages. The very earliest mentions of anyone called Arthur in the records indicate that he died in a battle fought in Angus, Scotland.

Adomnan of Iona's Life of Columba (circa 697) tells us that Artur son of Aedan was present when his father was "ordained" king of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574. The saint predicted the fates of Aedan's sons, announcing that Artur would "fall in battle, slain by enemies". Adomnan assured his readers that this prophecy came true when Artur and at least one of his brothers was killed in a "battle of the Miathi".

The Miathi, or Maeatae, were a Pictish tribe: essentially, they held the low-lying lands to the south and east of the Highland massif. Another Latinate term for these people was Verturiones.

The Irish annals, which drew at least some of their information from the records kept by Columba's monks on the Isle of Iona, specify that Artur son of Aedan died in a "battle of Circenn". This refers to the Pictish province which was roughly contiguous with today's Angus and the Mearns. The term Circenn combined the Gaelic cir, meaning a "comb" or "crest", and cenn, "heads". Circenn, then, was the land of the Comb-heads. This tells us that the Miathi Picts modelled their appearance on their totem beast, the boar (rather like their compatriots in the Orkneys, the Orcoi, from orc - a young boar). Indeed, it is possible that the Latinate name for the Verturiones tribe combines verres and turio and indicates the "offshoots" or "offspring" of the "boar", while the very term "Pict" (variant, "Pecti", "Pecht") quite possibly derived from the Latin pecten, a "comb".

Now, let's look at "Camlann" - the traditional name for Arthur's last battle. Its first appearance in the records comes in an entry interpolated into the Welsh Annals, where it refers to a gueith cam lann or "strife of cam lann". By the time this came to be written down, the region in which Artur son of Aedan died was speaking a version of Northumbrian Old English which became the dialect known as Lowland Scots. In that dialect, cam lann would mean "comb land".

In other words, "Camlann" is merely an anglicised version of the Gaelic Circenn, the land of the "Comb-heads" in which the first Arthur on record fell in a cataclysmic battle.

Culhwch and Olwen

One of the oldest of the Welsh (i.e. British) tales to feature Arthur is that of Culhwch ac Olwen. It forms a sort of mythologised, potted account of Arthur's career, culminating in the desperate and bloody hunt for a king who - for his sins - was turned into a boar. This hunt begins with a violent amphibious landing, at a site which can be identified as Cruden Bay, on the Aberdeenshire coast, after which Arthur is met by the "saints of Ireland" who "besought his protection". The dreadful Boar-King is challenged and chased from Esgeir Oerfel, the "Cold Ridge" of the Grampians, the Boar-King making his way across country towards Llwch Tawy (Loch Tay) before he is intercepted by Arthur and his men and driven into a river.

In The King Arthur Conspiracy I identified the treacherous Boar-King as Morgan the Wealthy, a renegade British prince who abducted Arthur's wife, Gwenhwyfar, and escaped into the land of the Miathi Picts (his bolt hole appears to have been the fortified Hill of Tillymorgan in Strathbogie). The site where Morgan finally came to grief is marked by the "Morganstone" on the west bank of the River Ericht, a short distance to the west of the Hill of Alyth in the great vale of Strathmore in Angus.

Arthurian Connections with Alyth

Before we proceed, let us consider some ancient references to Arthur and his family in the context of Alyth and its immediate vicinity.

In addition to having a son named Artur or Artuir, King Aedan of the Scots had a daughter called Muirgein. According to Whitley Stokes, editing and translating the Martyrology of a 9th-century Irish monk called Oengus, Muirgein daughter of Aedan was born "in Bealach Gabrain".

The inability of certain scholars to find a "Bealach Gabrain" in Scotland has led some to argue that Muirgein daughter of Aedan was utterly unconnected with Artur son of Aedan. But place-names evolve. The Gaelic term bealach, meaning a "pass" or "gorge", usually appears as "Balloch" on today's maps. There is a "Balloch" which runs along the feet of Barry Hill and the adjacent Hill of Alyth in Strathmore.

Furthermore, this "Balloch" or bealach was in a region named after the grandfather of Artur and Muirgein. Gabran was the father of Aedan. He ruled the Scots for twenty years until his death in about AD 559 and gave his name to the region of Gowrie (a corruption of Gabran). The "Balloch" near Alyth was in Gabran's land (Gabrain) and lies close to the town of Blairgowrie, which also recalls the name of Arthur's grandfather. The "Balloch" at the foot of the Hill of Alyth was almost certainly the "Bealach Gabrain" or "pass of Gowrie" where Arthur's (half-)sister, Muirgein daughter of Aedan mac Gabrain, was born. To pretend that the Balloch of Gowrie could not have been "Bealach Gabrain" because they are not spelled the same way these days is tantamount to claiming that Londinium and London could not have been the same place.

So Arthur's sister, Muirgein (latterly, Morgan le Fay), was born near Alyth. Writing in about 1527, the Scottish historian Hector Boece also indicated that Arthur's wife was buried at Meigle, which is just a mile or two south of Alyth. Hector Boece's local tradition recalled Gwenhwyfar as Vanora (via Guanora) and claimed that she had been held hostage in the Iron Age hill-fort atop Barry Hill, adjacent to the Hill of Alyth, before she was executed and buried in what is now the kirkyard at Meigle. A carved Pictish standing stone, now on display at the Meigle museum, reputedly depicts the execution or burial of Arthur's wife.

Y Gododdin

One of the best sources of information about Arthur's last battle is the ancient epic, Y Gododdin. This was composed and sung by Aneirin, a British bard of the Old North, and can be dated to circa AD 600 (the date of Arthur's last battle is given in the Irish annals as, variously, AD 594 and 596).

Unfortunately, the relevance of Aneirin's elegiac tribute to the warriors of Lothian (the "Gododdin") has been missed by scholars who want to believe that the poem bemoans the destruction of a British war-band from the Edinburgh area which had the misfortune to be wiped out at a mythical battle fought at Catterick in North Yorkshire. No evidence exists that any such battle was fought. The Angles (forerunners of the English) preferred not to recollect their defeats but were happy to remember, and to boast about, their victories. If the Angles of Northumbria had indeed obliterated a British band of heroes from Lothian at Catterick, we might assume that they would have remembered doing so. And no scholar has yet explained the presence of "Irishman and Picts" at this imaginary battle in Anglian territory.

A verse or two of Y G[ododdin, added at a later date than the original composition, described a battle fought in Scotland (Strathcarron) in AD 642 and the death in that battle of a Scottish king who just happened to be a nephew of Artur son of Aedan. This interpolation does at least suggest that the subject of the original poem was a battle fought in roughly the same area (Scotland) by the family of Artur and his father Aedan. The Y Gododdin poem also mentions various famous warriors who appear in the early accounts of Arthur's career and who were contemporary with Artur son of Aedan.

One surviving version of Y Gododdin even mentions Artur/Artuir by name:

Gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef Arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

Confused by the misidentification of the battle sung about by Aneirin in Y Gododdin, and the assumption that Arthur himself could not have been present at that battle, scholars have persistently mistranslated this verse - mostly in an attempt to render the second half of the second line, "He was no Arthur". But Aneirin's verse should properly be translated thus:

Black ravens [warriors] sang in praise of the hero [Welsh, arwr]

of Circenn [transliterated into Welsh as "caer ceni"]. He blamed Arthur;

the dogs cursed in return for our wailing/lamentation ...

Aneirin indicated, in his Y Gododdin elegy, precisely where the final battle took place:

Eil with gwelydeint amallet

y gat veirch ae seirch greulet

bit en anysgoget bit get ...

Which translates as:

Again they came into view around the alled,

the battle-horses and the bloody armour,

still steadfast, still united ...

The "alled" was Aneirin's Welsh-language attempt at the Gaelic Allaid - also Ailt - or the Hill of Alyth.

Breuddwyd Rhonabwy

The extraordinary medieval Welsh tale of The Dream of Rhonabwy actually provides a description of the scene in the hours before Arthur's last battle was fought. The visionary seer, Rhonabwy, finds himself crossing a great plain with a river running through it (Strathmore). He is met by a character call Iddog, "Churn of Britain", who admits that it was he who caused the cataclysmic "battle of Camlan" by betraying Arthur. In company with Iddog, Rhonabwy approaches the "Ford of the Cross" (Rhyd-y-Groes) on the river. A great army is encamped on either side of the road and Arthur is seated on a little flat islet in the river, beside the ford.

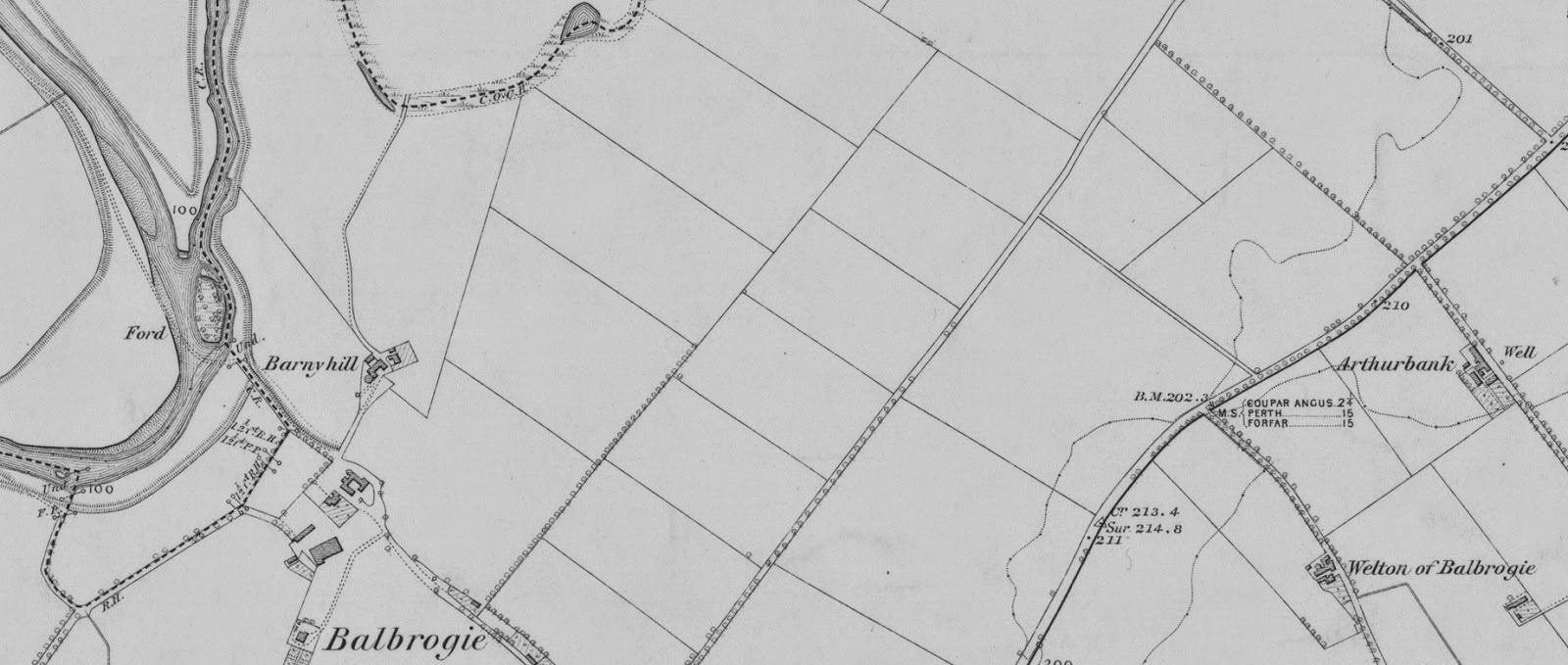

The topography precisely matches the detail from a 19th-century Ordnance Survey map of the area around Alyth seen at the top of this post. On the right-hand side of the detail is the ridge known as Arthurbank, which lies along the River Isla, opposite the junction of the River Ericht with the River Isla (a few miles down the Ericht from the site of the Morganstone). A little flat islet lies in the River Isla, close to the Arthurbank shore, and a ford runs alongside this little islet, exactly as described in the Welsh account of Rhonabwy's dream.

Aneirin also mentioned this ford in his Y Gododdin poem as rhyd benclwyd - the "ford" of the "grey" or "holy mount". There is, indeed, a Greymount marked on the map, a short distance to the north of the ford on the Isla. In his Agriculture of Perthshire, published in 1799, the Rev. Dr Robertson described the discovery of a "large Druidical temple" at Coupar Grange, adjacent to this ford. A standing stone found in this "temple" would no doubt have been rebranded a "cross" by the early Christians, so that the ford across the Isla, beside the little flat islet, would have become known as the Ford of the Cross (Rhyd-y-Groes), as described in The Dream of Rhonabwy, or the "Ford of the Grey/Holy Mount" (rhyd benclwyd) as described by Aneirin.

Until the late 18th century, an Arthurstone stood at the south-eastern edge of the Arthurbank ridge (its presence is still marked on the map). This Arthurstone corresponds to the Morganstone, a few miles away up the River Ericht, and marks the spot where Arthur fell in his battle with the Boar-King of the Miathi Picts in the land of the "crested" Comb-heads, Camlann.

The Head of the Valley of Sorrow

After the battle, Arthur's wife Gwenhwyfar was executed and buried only a mile or so away at Meigle. The legend of Culhwch and Olwen (which, interestingly, features a treacherous individual identified as Grugyn, who also appears in Aneirin's Y Gododdin) tells us that, after the battle at the river with the dangerous Boar-King, Arthur and his heroes once more "set out for the North" to overcome a fearsome witch. She was found inside a cave at Penn Nant Gofid - the "Head of the Valley of Sorrow"- on "the confines of Hell" (which we can interpret as the edge of the territory controlled by those boar-like Miathi Picts). The Welsh gofid ("sorrow/trouble/affiction/grief") appears to have been something of a pun, for another Welsh word for sorrow or grief is alaeth (compare Ailt, Allaid and Alyth, the "Head of the Valley of Alyth" being the very hill on which Arthur's wife is rumoured to have been held prisoner before her execution and burial nearby at Meigle).

In the Welsh tale, this witch is known as Orddu (that is, Gorddu - "Very Black"). A similar legend from the Isle of Mull, whose Arthurian associations have been overlooked for far too long, names the troublesome wife as Corr-dhu ("Black-Crane").

We might also note that the 9th-century Welsh monk known as Nennius described a "wonder" of Scotland in the form of "a valley in Angus, in which shouting is heard every Monday night; Glend Ailbe is its name, and it is not known who makes this noise."

Nennius's Glend Ailbe seems to be a corruption of the Gaelic word for a valley (glen) and the River Isla, or perhaps the Allaid or Hill of Alyth, which dominates the vale of Strathmore. The mysterious shouting in this "Valley of Sorrow" was reputedly heard ever Monday night. And we know from Aneirin's eye-witness account of Arthur's last battle that it came to an end on a Monday.

This is just some of the evidence for Arthur having fallen in the vicinity of Alyth. There is plenty more to come in The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - including descriptions of the Pictish symbol stones, found close to the site of that battle, which actually depict the Grail in use!

I'll let you know when the book is about to be published.

Friday, 10 January 2014

A Race Against Time

I came across this press piece a few days ago. It's maybe not quite as bad as it first appears: nobody seems to be suggesting that we build new houses on top of the Old Oswestry hill-fort, only on the fields immediately adjacent. But what I found most interesting about the article is what it says of the 3,000 year old hill-fort - that Old Oswestry is "said to be the birthplace of Guinevere, King Arthur's Queen."Ooops, let's back up a bit there. "Guinevere" is a medieval invention. Or, rather, it's a Medieval French rendition of a Welsh name - Gwenhwyfar. It's just one of those Arthurian anomalies that we keep referring to the original characters by the wrong names. Forget Guinevere: she didn't exist. Let's call her Gwenhwyfar instead.

And while we're at it, let's stop saying "King Arthur", because he didn't exist either. His people remembered him as "the emperor Arthur". Or we could just call him "Arthur". But "King Arthur" is purely mythical, even though Arthur himself was real.

Anyway, there is a tradition - apparently - that Gwenhwyfar, the wife of Arthur the Emperor, was born at Old Oswestry. I was quite thrilled to read that, because in "The King Arthur Conspiracy" I endeavoured to trace Gwenhwyfar's family background, and was able to pin it down to the Flintshire region of North Wales. Oswestry, on the Welsh border, is just to the south of that part of the world, and was quite possibly part of the sub-kingdom ruled by Gwenhwyfar's father.

I identified Gwenhwyfar's father as Caradog Freichfras ("Strong-Arm"), who was initially associated with the kingdom of Glywysing, immediately to the south of Oswestry. However, along with a number of other Arthurian heroes, Caradog seems to have shifted his base of operations northwards, initially to the Tegeingl sub-kingdom of Gwynedd, immediately to the north of (and possibly incorporating) Oswestry.

The Iron Age hill-fort believed to have been Gwenhwyfar's birthplace is also pretty close to the parish of Llangollen. This was home to an individual who became known as St Collen, although I argue that he was better known as (St) Cadog - another princeling of South Wales who moved, first into North Wales and, later, into central Scotland. Cadog - or Collen - appears to have functioned as a foster-father figure to Gwenhwyfar, or perhaps as the Druidic leader of her maidenly cult, and it is rather telling to discover that a Croes Gwenhwyfar - "Gwenhwyfar's Cross" - exists at Llangollen.

In other words, there is a fair amount of evidence which places the young Gwenhwyfar in the general area of Oswestry - before she, like so many of the others, moved north into what is now Scotland - and so we cannot write off the possibility that she was indeed born in the Iron Age hill-fort of Old Oswestry.

But that's not really the point of this post. Neither, for that matter, is any hand-wringing or soul-searching over the desirability of a new housing estate next door to Gwenhwyfar's birthplace - although that issue might serve as a sort of metaphor for what this post is all about.

It's about the race against time that we're currently in. Let me explain:

We live in unprecendented times. The internet, for example, is like nothing humanity that has ever known. So much knowledge at our fingertips! Researching Arthur and his people - and, for example, narrowing down the location of his last battle, as I did in The King Arthur Conspiracy and, in more detail, in my forthcoming The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - would have been immensely more time-consuming and expensive than it was.

However ... we also live in precedented times. I again cover this in The Grail, which is very much an exploration of the three "ages" of civilisation. We are currently being bullied out of the "Human age", which is characterised by liberal democracy and scientific materialism, by a resurgence of medieval "Heroic age" values, which we can characterise as dominated by religious fanaticism and extreme social inequality. This regression - the determination of some to tug us back into the kind of society which existed during the Middle Ages - is not really possible. It will lead (inevitably, I believe) to the collapse of our civilisation.

The internet is a fascinating product of our times. It is, in many ways, the ultimate "Human age" invention - possible only because of the technological infrastructure that was created by science, and thoroughly democratic, in that it is available to anybody. But the infrastructure necessary for the maintenance of a viable internet might not survive for long, and the anti-democratic instincts of those religious and political extremists who are forcing us back towards the "Heroic age" of times past are unlikely to favour the internet in its current form (although the internet is also one of the great purveyors of "Heroic age" thought, as uninformed opinion usurps the place of evidence-based logical reasoning and hysterical, paranoid memes spread like wildfire).

So, those of us who are fortunate enough to have access to the Global City which is the internet should really be using it to the best of our abilities. When it goes, it's gone - and our descendants will wonder at the race of supermen who could communicate instantaneously with millions across great distances, and who could access any information they required, just like that.

Do you really want your great-grandchildren to know that you had access to the greatest library the world has ever known, and the ability to exchange information with a massive global community - and all you did was post pictures of cats?

One of the ways in which the "Heroic age" is fighting back is through the rewriting of history. Michael Gove's cretinously empty-headed intervention in the matter of the First World War (which he seems to think was a rare old lark, sadly misreported ever since by "left-wing" academics and sit-com writers) shows that the religious-aristocractic view of the past, laced with ignorant flag-waving nationalism, is actively seeking to take control of history. Forget all those First World War poets who raged and railed against the hellish nightmare of the Western Front. No: a dimwitted politician now tells us that the war was a Good Thing, and anyone who questions that must be a "left-wing" radical.

In fact, the "Heroic age" has always rewritten history. It does so in order to cover its tracks and to pervert everyone's idea of the present. A government which is absolutely devoted to recreating the old aristocracy does not want you to think that the aristocratic officers of the First World War, or the aristocrats who sent so many millions to their deaths, were incompetent oafs. But the brainless attitude voiced by Michael Gove (Secretary of State for Education, would you believe?!) is symptomatic of a mindset that would happily send millions more to their deaths because they never learnt the lessons of history (how could they? Gove had already rewritten the book). And it's precisely that sort of thing that will undermine our civilisation.

Before we lose the internet, then - before we are banned from using it (because it's too democratic) or the infrastructure necessary to keep it going disintegrates (because it's "too expensive") - those of us who care about history really need to be making the most of our unprecedented opportunities to explore the past.

The "Heroic age" lied to us - repeatedly - about Arthur and his people. It was the "Heroic age" that invented the mythical "King Arthur" and changed the name of his wife from the authentic Gwenhwyfar to the familiar "Guinevere". And, let's face it, having lied to us before, it will lie to us again, given half a chance.

The only thing we can do is to uncover the historical truth, before the opportunity to do so is taken away from us. Arthur's last battle was fought at or near Alyth, in Scotland. A bit of determined research (internet and traditional) confirms this. But the "Heroic age" will have you believing that it happened somewhere else. Probably in the south. Evidence? Forget it. The "Heroic age" doesn't need evidence. It believes what it believes, and expects everyone else to believe it too. Evidence, be damned!

We could do our descendants a great big favour by using the internet intelligently, to challenge the foolish stories peddled by "Heroic age" propagandists. "King Arthur" never existed - he was an English invention - and the myth has always stood in the way of proper investigation. But tracing the historical Arthur is possible (and enjoyable), especially when we have all the resources of the internet at our command. Of course, the dogmatic voices of the "Heroic age" will shriek and shout and throw their little tantrums, but our great-grandchildren have the right to know what happened in the past. We have a duty to tell them, and not to let the past remain obliterated and re-engineered by fanatical demagogues, for whom everything must defend an extremist religious and/or political point-of-view.

So, in that sense, the story at the top of this post is a kind of metaphor. We are able - if we choose - to find out a great deal about Gwenhwyfar and her (possible) birthplace. But that won't last forever. Like the Iron Age hill-fort in which Arthur's wife was quite possibly born, there is a threat looming. The enemies of the truth are advancing.

There is still time to save the past from their bigoted opinions. But we do have to act.

Houses next door to Gwenhwyfar's birthplace? I'm not so worried about that, to be honest. Just so long as we succeed in uncovering and explaining who Gwenhwyfar was, while we still have the chance.

Thursday, 18 October 2012

Arthur's Last Battle - More Evidence

In the last blogspot, I suggested that Camlann - the name by which Arthur's last battle is commonly known - was not, in fact, a place-name. Rather, it meant something like "Broken Sword". As such, it was far more descriptive of the cataclysmic outcome than a mere place-name could ever be.

It was the battle in which Arthur's sword failed him, in which the "emperor" was mortally wounded, and which sealed the fate of Britain.

In my book, The King Arthur Conspiracy, I explain where the battle took place. It was along the River Isla in Angus. Arthur's forces occupied the south bank of the river. His opponents were ranged along the hills to the north of the Isla. Arthur was standing by a standing stone, near the village of Meigle, when he was treacherously attacked from behind. He fought his way across the hollow plain to Arthurbank, beside the River Isla, where he fell.

A Breton poem recalls something of this. It is entitled Bran, which means "Raven" or "Crow", and a translation can be found here: http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/celtic/ctexts/bran.html

In my book, I explain at some length why Bran was an alternative name for Arthur, and that the Welsh legend of Bendigeid Fran ("Blessed Raven") recalls the treachery which culminated in Arthur's last battle and his terrible wounding. The Breton poem of Bran would appear to have encapsulated the memory of those British refugees from the kingdom of Lothian who escaped to Brittany ("The Lesser Britain") after their homeland fell to the invading Angles in AD 638. They remembered their lost land as Leonais - the Land of the Lion - which, through the garbled yarns of the medieval storytellers, became the romantic "Lyonesse".

The poem tells us that "Bran the knight" was grievously wounded at "Kerloan fight". His side won, apparently - thanks, in large part, to "great Evan", who put the Saxons to flight (Evan, or Yvain, is the Frenchified version of Owain, son of Urien, who was indeed present at Arthur's last battle; he was also Arthur's nephew). But Bran - who, in the poem, is designated "Bran-Vor's grandson", reminding us that Arthur was the grandson of the "great raven" (Bran mhor) whose given name was Gabran, King of the Scots - was "captive borne beyond the sea" to the place where he died.

The Breton poem, therefore, recalled the battle at which Arthur ("Bran") was mortally wounded as "Kerloan fight".

Now, Kerloan, or Kerlouan, is a district in Brittany, a long, long way from the site of Arthur's last battle. There is good reason, however, to suppose that the name of the Kerlouan region actually came from the site of Arthur's battle. The ker prefix is the same as the Welsh caer - a fortress, castle or citadel.

When I first tried to locate a "Castle of Louan" I thought of Arthur's grandmother, Lluan or Lleian, a British princess of Strathclyde who married Gabran mac Domangairt ("Bran-Vor", in Breton tradition) and gave birth to Arthur's father. Gabran himself gave his name to the Gowrie region of Scotland, and in The King Arthur Conspiracy, I note that Arthur's half-sister, Muirgein, was born in Bealach Gabrain, the "Pass of Gabran", which I suggest was the low-lying pass or Balloch which lies beneath the Hill of Alyth in Perthshire, not far from the town of Blairgowrie ("Battlefield of Gabran's Land"). I wondered, then, whether the Hill of Alyth, or one of its neighbouring hills, such as the Hill of Loyal or Barry ("Ridge of the King") Hill, was once thought of as the "Castle of Lluan".

In fact, the louan element in the Breton Kerlouan comes from Saint Louan - or Luan, as he was known in Ireland. The Welsh form of his name - Llywan - recalls a famous pool which, in Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Briton, Arthur discusses with one of his comrades after they have both seen action in and around Dumbarton and Loch Lomond.

In Scotland, Luan is better known as St Moluag. He was a contemporary of Artuir mac Aedain, and is said to have held a race with St Columba to determine who should have possession of the island of Lismore, near Oban. Moluag is principally associated with Lismore, although there were churches dedicated to him throughout the Western Isles and northern Scotland (he appears to have spent a great deal of time amongst the Picts). One tradition holds that he cured the holy Molaisse (Arthur's nephew, Laisren) of an ulcer. He was mentioned in 1544 as the patron saint of Argyll - the heartland of the Scots of Dal Riata, whose king was Arthur's father - and his death is dated to AD 592.

Other versions of his name include Elvan, Elven, Lua, Lugaidh, Molloch and Murlach (the Gaelic murlach actually means a "kingfisher" or a "fishing basket"). There is only one place in Scotland at which he is remembered as Luan.

St Luan's Church stands in Alyth, Perthshire. The Alyth Arches (see photo above) are all that remain of an earlier church, built on the site of a sixth-century chapel named in honour of St Luan. Notably, as well as being the patron saint of Argyll, Luan was the patron of Alyth, and his fair - "Simmalogue Fair", a corruption of St Moluag - was held there.

Given that Moluag's chapel would appear to have existed by the time of his death in circa 592, we can presume that the "Fort of Luan" was already there when Arthur fought his last battle in the immediate vicinity in AD 594. This was the Kerlouan remembered by British refugees from Arthur's land who escaped to Brittany and named a coastal region there after the site of Luan's Citadel.

The Hill of Alyth features in a more-or-less contemporary poem of Arthur's last battle. It was a place of supreme strategic or symbolic importance - one of Arthur's earlier enemies, a king of the southern Picts named Galam Cennaleth - bore an epithet meaning "Chief of Alyth". A very ancient tradition holds that Arthur's queen, Gwenhwyfar, was held prisoner at Alyth by the "Pictish" king Mordred. The name Alyth means something like "The Height" or "The Strength". The Britons spelled it Alledd - phonetically, much the same as Alyth - and it is in this form that it occurs in the epic poem Y Gododdin:

Again the battle-shout about the Alledd,

The battle-horses and bloodied armour,

Until they shook with the passion of the great battle ...

This, then, was the scene of Arthur's final conflict. His own position was to the south of the Hill of Alyth, and is recalled at the ridge of Arthurbank (where, until the 1790s, an Arthurstone stood). Between the hill and the ridge lay the chapel, cell or monastery named after St Moluag - the Fort of Luan, patron saint of Alyth, or, as the British refugees in Brittany remembered it, Kerlouan.

The Breton poem indicates that Lord Bran (Arthur) died in a tower or keep "beyond the sea". He had despatched a messenger to summon his mother from "Leon-land" (the Land of the Lion, or Leonais, as the exiles thought of their Lothian homeland). The mother of the historical Arthur was indeed a princess of Lothian.

And, in an interesting twist on what caused Arthur's last battle, the poem suggests that Arthur's messenger was a "false sentinel" with a "mischief-working smile". But to know how that relates to Arthur's last battle, you'll just have to buy The King Arthur Conspiracy!

Anyway - the long and the short. Here, in the form of the Breton poem of Bran, we have another source for the location of Arthur's final battle. The Britons of Lothian remembered it well: in his poem, "The Gododdin", the British bard Aneirin recollected that Arthur's enemies had swarmed around the Hill of Alyth. Those of his fellow countrymen who fled to Brittany remembered that the battle had been fought around a settlement associated with Luan, patron saint of Alyth.

So, anyone looking for a place called "Camlann" where Arthur's last battle was fought is likely to find nothing, especially if they are foolish enough to go looking for it in England. The clues are unmistakeable. Arthur fell at Arthurbank in Scotland, near the Hill of Alyth and the Church of St Luan. It just so happens that, as he hacked his way towards Arthurbank, he crossed a hollow plain known, to this day, as the Mains of Camno.

It was the battle in which Arthur's sword failed him, in which the "emperor" was mortally wounded, and which sealed the fate of Britain.

In my book, The King Arthur Conspiracy, I explain where the battle took place. It was along the River Isla in Angus. Arthur's forces occupied the south bank of the river. His opponents were ranged along the hills to the north of the Isla. Arthur was standing by a standing stone, near the village of Meigle, when he was treacherously attacked from behind. He fought his way across the hollow plain to Arthurbank, beside the River Isla, where he fell.

A Breton poem recalls something of this. It is entitled Bran, which means "Raven" or "Crow", and a translation can be found here: http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/celtic/ctexts/bran.html

In my book, I explain at some length why Bran was an alternative name for Arthur, and that the Welsh legend of Bendigeid Fran ("Blessed Raven") recalls the treachery which culminated in Arthur's last battle and his terrible wounding. The Breton poem of Bran would appear to have encapsulated the memory of those British refugees from the kingdom of Lothian who escaped to Brittany ("The Lesser Britain") after their homeland fell to the invading Angles in AD 638. They remembered their lost land as Leonais - the Land of the Lion - which, through the garbled yarns of the medieval storytellers, became the romantic "Lyonesse".

The poem tells us that "Bran the knight" was grievously wounded at "Kerloan fight". His side won, apparently - thanks, in large part, to "great Evan", who put the Saxons to flight (Evan, or Yvain, is the Frenchified version of Owain, son of Urien, who was indeed present at Arthur's last battle; he was also Arthur's nephew). But Bran - who, in the poem, is designated "Bran-Vor's grandson", reminding us that Arthur was the grandson of the "great raven" (Bran mhor) whose given name was Gabran, King of the Scots - was "captive borne beyond the sea" to the place where he died.

The Breton poem, therefore, recalled the battle at which Arthur ("Bran") was mortally wounded as "Kerloan fight".

Now, Kerloan, or Kerlouan, is a district in Brittany, a long, long way from the site of Arthur's last battle. There is good reason, however, to suppose that the name of the Kerlouan region actually came from the site of Arthur's battle. The ker prefix is the same as the Welsh caer - a fortress, castle or citadel.

When I first tried to locate a "Castle of Louan" I thought of Arthur's grandmother, Lluan or Lleian, a British princess of Strathclyde who married Gabran mac Domangairt ("Bran-Vor", in Breton tradition) and gave birth to Arthur's father. Gabran himself gave his name to the Gowrie region of Scotland, and in The King Arthur Conspiracy, I note that Arthur's half-sister, Muirgein, was born in Bealach Gabrain, the "Pass of Gabran", which I suggest was the low-lying pass or Balloch which lies beneath the Hill of Alyth in Perthshire, not far from the town of Blairgowrie ("Battlefield of Gabran's Land"). I wondered, then, whether the Hill of Alyth, or one of its neighbouring hills, such as the Hill of Loyal or Barry ("Ridge of the King") Hill, was once thought of as the "Castle of Lluan".

In fact, the louan element in the Breton Kerlouan comes from Saint Louan - or Luan, as he was known in Ireland. The Welsh form of his name - Llywan - recalls a famous pool which, in Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Briton, Arthur discusses with one of his comrades after they have both seen action in and around Dumbarton and Loch Lomond.

In Scotland, Luan is better known as St Moluag. He was a contemporary of Artuir mac Aedain, and is said to have held a race with St Columba to determine who should have possession of the island of Lismore, near Oban. Moluag is principally associated with Lismore, although there were churches dedicated to him throughout the Western Isles and northern Scotland (he appears to have spent a great deal of time amongst the Picts). One tradition holds that he cured the holy Molaisse (Arthur's nephew, Laisren) of an ulcer. He was mentioned in 1544 as the patron saint of Argyll - the heartland of the Scots of Dal Riata, whose king was Arthur's father - and his death is dated to AD 592.

Other versions of his name include Elvan, Elven, Lua, Lugaidh, Molloch and Murlach (the Gaelic murlach actually means a "kingfisher" or a "fishing basket"). There is only one place in Scotland at which he is remembered as Luan.

St Luan's Church stands in Alyth, Perthshire. The Alyth Arches (see photo above) are all that remain of an earlier church, built on the site of a sixth-century chapel named in honour of St Luan. Notably, as well as being the patron saint of Argyll, Luan was the patron of Alyth, and his fair - "Simmalogue Fair", a corruption of St Moluag - was held there.

Given that Moluag's chapel would appear to have existed by the time of his death in circa 592, we can presume that the "Fort of Luan" was already there when Arthur fought his last battle in the immediate vicinity in AD 594. This was the Kerlouan remembered by British refugees from Arthur's land who escaped to Brittany and named a coastal region there after the site of Luan's Citadel.

The Hill of Alyth features in a more-or-less contemporary poem of Arthur's last battle. It was a place of supreme strategic or symbolic importance - one of Arthur's earlier enemies, a king of the southern Picts named Galam Cennaleth - bore an epithet meaning "Chief of Alyth". A very ancient tradition holds that Arthur's queen, Gwenhwyfar, was held prisoner at Alyth by the "Pictish" king Mordred. The name Alyth means something like "The Height" or "The Strength". The Britons spelled it Alledd - phonetically, much the same as Alyth - and it is in this form that it occurs in the epic poem Y Gododdin:

Again the battle-shout about the Alledd,

The battle-horses and bloodied armour,

Until they shook with the passion of the great battle ...

This, then, was the scene of Arthur's final conflict. His own position was to the south of the Hill of Alyth, and is recalled at the ridge of Arthurbank (where, until the 1790s, an Arthurstone stood). Between the hill and the ridge lay the chapel, cell or monastery named after St Moluag - the Fort of Luan, patron saint of Alyth, or, as the British refugees in Brittany remembered it, Kerlouan.

The Breton poem indicates that Lord Bran (Arthur) died in a tower or keep "beyond the sea". He had despatched a messenger to summon his mother from "Leon-land" (the Land of the Lion, or Leonais, as the exiles thought of their Lothian homeland). The mother of the historical Arthur was indeed a princess of Lothian.

And, in an interesting twist on what caused Arthur's last battle, the poem suggests that Arthur's messenger was a "false sentinel" with a "mischief-working smile". But to know how that relates to Arthur's last battle, you'll just have to buy The King Arthur Conspiracy!

Anyway - the long and the short. Here, in the form of the Breton poem of Bran, we have another source for the location of Arthur's final battle. The Britons of Lothian remembered it well: in his poem, "The Gododdin", the British bard Aneirin recollected that Arthur's enemies had swarmed around the Hill of Alyth. Those of his fellow countrymen who fled to Brittany remembered that the battle had been fought around a settlement associated with Luan, patron saint of Alyth.

So, anyone looking for a place called "Camlann" where Arthur's last battle was fought is likely to find nothing, especially if they are foolish enough to go looking for it in England. The clues are unmistakeable. Arthur fell at Arthurbank in Scotland, near the Hill of Alyth and the Church of St Luan. It just so happens that, as he hacked his way towards Arthurbank, he crossed a hollow plain known, to this day, as the Mains of Camno.

Labels:

Alyth,

Argyll,

Arthur,

Arthurbank,

Artuir mac Aedain,

Bran,

Brittany,

Gwenhwyfar,

King Arthur Conspiracy,

Loch Lomond,

Lothian,

Meigle,

Muirgein,

Raven,

River Isla,

St Columba,

St Moluag,

Strathclyde,

Y Gododdin

Sunday, 23 September 2012

Arthur's Ghost?

In The King Arthur Conspiracy, I describe a crisis apparition which is said to appear whenever a senior clansman of Arthur's descendants, the Campbells (a cadet branch of the Clann Arthur), is about to die.

The apparition takes the form of an ancient galley, which appears over Loch Fyne, close to the site of Arthur's settlement at Strachur (the original base of the MacArthur clan) and then sails westward, over the land, towards the place of Arthur's burial.

The last reported sighting of the ghostly galley of Loch Fyne was in 1913. Reputedly, three men are visible on its deck. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, three men crewed the ship which carried Arthur's mortal remains to the Isle of Avalon.

Another crisis apparition is worthy of mention here - because it is not included in The King Arthur Conspiracy. This is the "best-known and most dreadful spectre in the West Highlands". It's the phantom of a headless horseman which haunts the Glen More region of the Isle of Mull.

The spectre was last seen, apparently, in 1958. It is associated with the Clan Maclaine of Lochbuie, and its appearance heralds the death of a senior member of the clan. Distantly related to the neighbouring Macleans of Duart, the Maclaines give the Gaelic version of their name as Mac'ill-Eathain. Translated into English, this would be "Son of the Lad/Servant of Aedan".

Aedan (the name of Arthur's father, Aedan mac Gabrain) is a version of the Irish Aodhan, meaning "Little fiery one". It was originally pronounced something like "Eye-than" and appeared in Welsh as Aeddan. A later variant was Eathan, from which the Maclaines and Macleans take their clan name.

The phantom headless horseman of Glen More is known as Eoghann a' Chinn Bhig ("Ewen of the Little Head"). The name Eoghan appears to have meant "well-born" (literally, "yew-born"), and variants of the name crop up frequently in the early Arthurian literature. Two historical rulers of the British kingdom of North Rheged - both of them contemporaries, kinsmen and comrades of Arthur - bore the names Urien and Owain, each of which compares with the Gaelic Eoghan.

Towards the end of The King Arthur Conspiracy, I trace the descendants of Arthur to the Isle of Ulva, off the west coast of the Isle of Mull. The Clan MacQuarrie claims its descent from one Guaire son of Aedan. Mentioned in Adomnan's Life of St Columba (circa 697 AD), this Guaire was the strongest or most valiant layman in the Scottish kingdom of Dal Riata. Arthur's father, Aedan, was ordained King of Dal Riata by St Columba in 574 AD. The name Guaire appears to be related to the Gaelic cura, a "protector" or "guardian". I noted in my book that the main village of the MacQuarries on Ulva was Ormaig, where a piper named MacArthur founded a famous piping school. The ancestral burial ground of the MacQuarries, close to the village of Ormaig, is known as Cille Mhic Eoghainn ("Kilvikewan'), the "Chapel of the Son/Sons of Ewen".

In addition to relating to the yew-tree, the name Eoghan might also have been associated specifically with another island which lies off the west coast of Mull. The Isle of Iona was known, as late as the 9th century AD, as Eo. It was the "Island of the Yew". Adomnan, who tells us about the death of Arthur in battle, referred to it as "the yewy isle" (Ioua insula). This was almost certainly because the sacred isle of Iona was considered an omphalos or "World-Navel", and was the site of the "World-Tree". This tree appears to have been known as Eo or Io - both meaning "yew".

In the context of Mull and its outlying islands - Ulva and Iona - it is possible, then, that the name Eoghan could mean "Yew-born" or "Born of Iona" or, indeed, both, Iona being the island of the sacred yew or World-Tree. Variants of the name were applied to some of Arthur's closest associates, and possibly to Arthur himself.

It is unclear exactly who Eoghann a' Chinn Bhig - Ewen of the Little Head - was, or when he lived. What we do know, however, is that he was a "Yew-born" youth of the Clan Maclaine, the Sons of the Lad (or Servant) of Aedan, the Aedan in question quite possibly being Arthur's father, Aedan mac Gabrain. In Hebridean tradition, the father of Arthur is sometimes identified as Iuthar (the MacArthur clan call him Iobhair), which also derives from iubhar, the Gaelic name for the "yew", and athair (Old Irish athir), "father".

The story of Ewen of the Little Head goes like this. Ewen had married a difficult, demanding woman who became known as Corr-dhu, the "Black Crane" (the crane was held sacred by the Druids, who believed that the letters of their alphabet were inspired by the shapes made by a crane's legs in flight; the tendency of Celtic seers to stand on one leg when making prophesies probably owed something to the crane). His wife insisted that Ewen demand more land, and eventually Ewen found himself in dispute with his uncle. Battle loomed.

On the eve of the battle, Ewen encountered a bean-nighe or Washer at the Ford. These supernatural washerwomen were adept at predicting death and disaster. Again, in The King Arthur Conspiracy, I indicate that Arthur's half-sister Muirgein ("Morgana") fulfilled the role of a Washer at the Ford.

Ewen demanded to know what the outcome of his battle with his uncle would be. The Washer made a strange prediction. If, on the morning of the battle, Ewen's wife provided him with some butter for his breakfast, without having to be asked, then Ewen would triumph. If no butter appeared at the breakfast table, Ewen would die.

Naturally, there was no butter for breakfast. Ewen went into battle mounted on his pony - generally described as a small black steed with a white spot on its forehead. It is said that the prints left by this pony's hooves are not like those of normal horses. Instead of being horseshoe-shaped, they are round indentations, "as if it had wooden legs". This is probably because, in Arthur's day, the familiar horseshoe had not been invented. His own war pony would have been shod with "hipposandals", a kind of iron plate or oval-shaped cup of metal which protected the sole of the hoof. These had been introduced into Britain under the Roman Empire.

The battle ended when Ewen's head was removed from his body by a single sword stroke. His headless body remained on his horse, which bolted. The horse finally came to the Lussa Falls in Glen More, where Ewen's body fell from its back. Ewen's headless body was reputedly buried there, before it was removed to the Isle of Iona. The site of his initial burial was close to the well-defended artificial island or "crannog" in Loch Sguabain (see photo at top of this post) which is still known as Caisteal Eoghainn a' Chinn Bhig ("Ewen of the Little Head's Castle").

Such ancient crannogs were very much a part of Arthur's world (there is one in Loch Arthur, near Dumfries). Otherwise, there are intriguing similarities in the Mull legend and the story of Arthur. Like Arthur, Ewen was married to a difficult woman who seems to have kept on at her husband to demand more land. It was she who caused the battle at which Ewen died - just as Arthur's wife Gwenhwyfar was held to blame for his last battle. In The King Arthur Conspiracy, I point out that Arthur's worst enemy in his final campaign was his uncle, just as Ewen went into battle against his uncle. And the prophecy of the Washer at the Ford (who so resembles Arthur's half-sister) indicated that success or disaster was dependent on the appearance of butter on the morning of the battle.

In one of the most revealing accounts of Arthur's last battle, as given in the Welsh tale of The Dream of Rhonabwy, we find that the battle was caused when Arthur's messenger deliberately relayed false, antagonistic messages to Arthur's opponents. The individual concerned (who is identified in The King Arthur Conspiracy) explains that, because of his provocative behaviour, he is known as Cordd Prydain - the "Churn of Britain".

Butter, of course, comes from a churn. And according to the Churn of Britain in The Dream of Rhonabwy, the troublemaker made himself scarce before the last day of the battle. It was not a lack of butter that morning which signalled disaster - it was the absence of a "Churn"! And because the "churn" in question was in cahoots with Arthur's troublesome wife, the churn's absence on the morning of the battle could be blamed on Gwenhwyfar, or the "Black Witch", as she is known in another Welsh tale.

The ghostly ancient galley which appears over Loch Fyne whenever a senior member of the Clan Campbell dies is a crisis apparition based - I suggest - on the ship which carried the wounded Arthur from Loch Fyne to the place of his burial. In The King Arthur Conspiracy, I explain how the ship, which was bound for the Isle of Iona, put in at Carsaig on the Isle of Mull. Arthur's body was carried up into the hills of Brolass. He was decapitated and his body buried at Sithean Allt Mhic-Artair ("Spirit-hill of the Stream of the Sons of Arthur") above the hamlet of Pennyghael ("Head of the Gael"). His head was then carried to the Isle of Iona for burial.

It is odd, then, to discover that the glen immediately to the east of Pennyghael is haunted by a headless horseman. The description of Ewen's pony corresponds to the exact sort of mount which Arthur and fellow horsemen or "knights" would have ridden into battle. And so, just as the imminent death of one of Arthur's Campbell descendants causes a crisis apparition to appear over Loch Fyne, so the death of another clansman from another line - the Maclaines, or the Sons of the Lad of Aedan - provokes another crisis apparition: that of a headless horseman. Arthur's headless body was buried by a stream on Mull, just as Ewen's headless body was supposedly buried beside the Lussa Falls nearby. And Arthur's head was carried to the adjacent Isle of Iona, as were Ewen's disinterred remains.

In the 19th century, visitors to the Isle of Iona were shown what was said to have been a carved stone commemorating Ewen of the Little Head. This was probably the Maclean's Cross (above), a 15th century carved stone, produced on Iona, which has the image of a mounted horseman on its base. It stood beside the medieval Street of the Dead. And in The King Arthur Conspiracy I indicate where, on the Street of the Dead, Arthur's head was finally laid to rest.

Could it be that the infamous headless horseman who haunts the route across Mull to the Isle of Iona was not an obscure member of the Clan Maclaine, but none other than that greatest of all heroes, Arthur son of Aedan? I think it might be, and that this is just one of the many Scottish traditions relating to Arthur, the Scottish prince who became a mythical hero.

The apparition takes the form of an ancient galley, which appears over Loch Fyne, close to the site of Arthur's settlement at Strachur (the original base of the MacArthur clan) and then sails westward, over the land, towards the place of Arthur's burial.

The last reported sighting of the ghostly galley of Loch Fyne was in 1913. Reputedly, three men are visible on its deck. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, three men crewed the ship which carried Arthur's mortal remains to the Isle of Avalon.

Another crisis apparition is worthy of mention here - because it is not included in The King Arthur Conspiracy. This is the "best-known and most dreadful spectre in the West Highlands". It's the phantom of a headless horseman which haunts the Glen More region of the Isle of Mull.

The spectre was last seen, apparently, in 1958. It is associated with the Clan Maclaine of Lochbuie, and its appearance heralds the death of a senior member of the clan. Distantly related to the neighbouring Macleans of Duart, the Maclaines give the Gaelic version of their name as Mac'ill-Eathain. Translated into English, this would be "Son of the Lad/Servant of Aedan".

Aedan (the name of Arthur's father, Aedan mac Gabrain) is a version of the Irish Aodhan, meaning "Little fiery one". It was originally pronounced something like "Eye-than" and appeared in Welsh as Aeddan. A later variant was Eathan, from which the Maclaines and Macleans take their clan name.

The phantom headless horseman of Glen More is known as Eoghann a' Chinn Bhig ("Ewen of the Little Head"). The name Eoghan appears to have meant "well-born" (literally, "yew-born"), and variants of the name crop up frequently in the early Arthurian literature. Two historical rulers of the British kingdom of North Rheged - both of them contemporaries, kinsmen and comrades of Arthur - bore the names Urien and Owain, each of which compares with the Gaelic Eoghan.

Towards the end of The King Arthur Conspiracy, I trace the descendants of Arthur to the Isle of Ulva, off the west coast of the Isle of Mull. The Clan MacQuarrie claims its descent from one Guaire son of Aedan. Mentioned in Adomnan's Life of St Columba (circa 697 AD), this Guaire was the strongest or most valiant layman in the Scottish kingdom of Dal Riata. Arthur's father, Aedan, was ordained King of Dal Riata by St Columba in 574 AD. The name Guaire appears to be related to the Gaelic cura, a "protector" or "guardian". I noted in my book that the main village of the MacQuarries on Ulva was Ormaig, where a piper named MacArthur founded a famous piping school. The ancestral burial ground of the MacQuarries, close to the village of Ormaig, is known as Cille Mhic Eoghainn ("Kilvikewan'), the "Chapel of the Son/Sons of Ewen".

In addition to relating to the yew-tree, the name Eoghan might also have been associated specifically with another island which lies off the west coast of Mull. The Isle of Iona was known, as late as the 9th century AD, as Eo. It was the "Island of the Yew". Adomnan, who tells us about the death of Arthur in battle, referred to it as "the yewy isle" (Ioua insula). This was almost certainly because the sacred isle of Iona was considered an omphalos or "World-Navel", and was the site of the "World-Tree". This tree appears to have been known as Eo or Io - both meaning "yew".

In the context of Mull and its outlying islands - Ulva and Iona - it is possible, then, that the name Eoghan could mean "Yew-born" or "Born of Iona" or, indeed, both, Iona being the island of the sacred yew or World-Tree. Variants of the name were applied to some of Arthur's closest associates, and possibly to Arthur himself.

It is unclear exactly who Eoghann a' Chinn Bhig - Ewen of the Little Head - was, or when he lived. What we do know, however, is that he was a "Yew-born" youth of the Clan Maclaine, the Sons of the Lad (or Servant) of Aedan, the Aedan in question quite possibly being Arthur's father, Aedan mac Gabrain. In Hebridean tradition, the father of Arthur is sometimes identified as Iuthar (the MacArthur clan call him Iobhair), which also derives from iubhar, the Gaelic name for the "yew", and athair (Old Irish athir), "father".

The story of Ewen of the Little Head goes like this. Ewen had married a difficult, demanding woman who became known as Corr-dhu, the "Black Crane" (the crane was held sacred by the Druids, who believed that the letters of their alphabet were inspired by the shapes made by a crane's legs in flight; the tendency of Celtic seers to stand on one leg when making prophesies probably owed something to the crane). His wife insisted that Ewen demand more land, and eventually Ewen found himself in dispute with his uncle. Battle loomed.

On the eve of the battle, Ewen encountered a bean-nighe or Washer at the Ford. These supernatural washerwomen were adept at predicting death and disaster. Again, in The King Arthur Conspiracy, I indicate that Arthur's half-sister Muirgein ("Morgana") fulfilled the role of a Washer at the Ford.

Ewen demanded to know what the outcome of his battle with his uncle would be. The Washer made a strange prediction. If, on the morning of the battle, Ewen's wife provided him with some butter for his breakfast, without having to be asked, then Ewen would triumph. If no butter appeared at the breakfast table, Ewen would die.

Naturally, there was no butter for breakfast. Ewen went into battle mounted on his pony - generally described as a small black steed with a white spot on its forehead. It is said that the prints left by this pony's hooves are not like those of normal horses. Instead of being horseshoe-shaped, they are round indentations, "as if it had wooden legs". This is probably because, in Arthur's day, the familiar horseshoe had not been invented. His own war pony would have been shod with "hipposandals", a kind of iron plate or oval-shaped cup of metal which protected the sole of the hoof. These had been introduced into Britain under the Roman Empire.

The battle ended when Ewen's head was removed from his body by a single sword stroke. His headless body remained on his horse, which bolted. The horse finally came to the Lussa Falls in Glen More, where Ewen's body fell from its back. Ewen's headless body was reputedly buried there, before it was removed to the Isle of Iona. The site of his initial burial was close to the well-defended artificial island or "crannog" in Loch Sguabain (see photo at top of this post) which is still known as Caisteal Eoghainn a' Chinn Bhig ("Ewen of the Little Head's Castle").

Such ancient crannogs were very much a part of Arthur's world (there is one in Loch Arthur, near Dumfries). Otherwise, there are intriguing similarities in the Mull legend and the story of Arthur. Like Arthur, Ewen was married to a difficult woman who seems to have kept on at her husband to demand more land. It was she who caused the battle at which Ewen died - just as Arthur's wife Gwenhwyfar was held to blame for his last battle. In The King Arthur Conspiracy, I point out that Arthur's worst enemy in his final campaign was his uncle, just as Ewen went into battle against his uncle. And the prophecy of the Washer at the Ford (who so resembles Arthur's half-sister) indicated that success or disaster was dependent on the appearance of butter on the morning of the battle.

In one of the most revealing accounts of Arthur's last battle, as given in the Welsh tale of The Dream of Rhonabwy, we find that the battle was caused when Arthur's messenger deliberately relayed false, antagonistic messages to Arthur's opponents. The individual concerned (who is identified in The King Arthur Conspiracy) explains that, because of his provocative behaviour, he is known as Cordd Prydain - the "Churn of Britain".

Butter, of course, comes from a churn. And according to the Churn of Britain in The Dream of Rhonabwy, the troublemaker made himself scarce before the last day of the battle. It was not a lack of butter that morning which signalled disaster - it was the absence of a "Churn"! And because the "churn" in question was in cahoots with Arthur's troublesome wife, the churn's absence on the morning of the battle could be blamed on Gwenhwyfar, or the "Black Witch", as she is known in another Welsh tale.

The ghostly ancient galley which appears over Loch Fyne whenever a senior member of the Clan Campbell dies is a crisis apparition based - I suggest - on the ship which carried the wounded Arthur from Loch Fyne to the place of his burial. In The King Arthur Conspiracy, I explain how the ship, which was bound for the Isle of Iona, put in at Carsaig on the Isle of Mull. Arthur's body was carried up into the hills of Brolass. He was decapitated and his body buried at Sithean Allt Mhic-Artair ("Spirit-hill of the Stream of the Sons of Arthur") above the hamlet of Pennyghael ("Head of the Gael"). His head was then carried to the Isle of Iona for burial.

It is odd, then, to discover that the glen immediately to the east of Pennyghael is haunted by a headless horseman. The description of Ewen's pony corresponds to the exact sort of mount which Arthur and fellow horsemen or "knights" would have ridden into battle. And so, just as the imminent death of one of Arthur's Campbell descendants causes a crisis apparition to appear over Loch Fyne, so the death of another clansman from another line - the Maclaines, or the Sons of the Lad of Aedan - provokes another crisis apparition: that of a headless horseman. Arthur's headless body was buried by a stream on Mull, just as Ewen's headless body was supposedly buried beside the Lussa Falls nearby. And Arthur's head was carried to the adjacent Isle of Iona, as were Ewen's disinterred remains.

In the 19th century, visitors to the Isle of Iona were shown what was said to have been a carved stone commemorating Ewen of the Little Head. This was probably the Maclean's Cross (above), a 15th century carved stone, produced on Iona, which has the image of a mounted horseman on its base. It stood beside the medieval Street of the Dead. And in The King Arthur Conspiracy I indicate where, on the Street of the Dead, Arthur's head was finally laid to rest.

Could it be that the infamous headless horseman who haunts the route across Mull to the Isle of Iona was not an obscure member of the Clan Maclaine, but none other than that greatest of all heroes, Arthur son of Aedan? I think it might be, and that this is just one of the many Scottish traditions relating to Arthur, the Scottish prince who became a mythical hero.

Thursday, 5 July 2012

King Lear

They might have lived a thousand years apart, but there are several connections between my two main subjects: Arthur and Shakespeare (Art & Will - geddit?). One of them is the legendary King Lear.

Like a great deal of Arthurian source material, the Lear legend has been ignored or overlooked because, on the face of it, it has nothing whatever to do with Arthur. The problem is one of names.

Historically, names are a problem. Let's take an individual from the lifetime of William Shakespeare. Sir Robert Cecil was the deformed, diminutive son of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, who served as chief minister and adviser to Elizabeth I. Robert succeeded his father, and went on to serve James I. Together, William and Robert Cecil were among the most ruthless and rapacious statesmen this country has ever known.

In 1603, Sir Robert Cecil became Baron Cecil of Essenden. The following year, he was made Viscount Cranborne. The year after that, he was elevated to the earldom of Salisbury. Over a period of just a couple of years, Cecil's name changed more than once. It was proper to refer to him as Lord Cranborne and, later, the Earl of Salisbury.

He also had nicknames, and plenty of them. Robertus Diabolus, the Toad, King James's 'little beagle' ...

Now, if we were to apply the "only one name per historical individual" rule which is routinely applied to Arthurian studies, then Sir Robert Cecil ceased to exist in about 1603 (he actually died in 1612). Out of nowhere appeared another person altogether, known as Salisbury.

And Will Shakespeare, of course, was not indicating Robert Cecil in the impish character of Robin Goodfellow ('Puck') or the malignant and deformed Richard 'Crookback' of Richard III. No way. Shakespeare would never have done such thing (except that he did).

You see the problem? If we insist that everybody in history only ever had the one name, and the one name only, we're not going to make much sense of history, are we? (In The King Arthur Conspiracy I also cite the example of General Schwarzkopf, who commanded the allied forces in the first Gulf War: he was also known as "Stormin' Norman" and "The Bear" - which would appear to have made him three different people.)

The character of Llyr (Irish: Lir) occurs in British tradition. His name meant "Sea". If we approach this character with our modern-day heads on, pretending that everyone throughout history has only ever had one name (so that Margaret Thatcher and the Iron Lady were obviously not the same person), then we are stuck. Who was Llyr, or Lir? No idea. Probably a myth.

Or maybe he was a lord of the sea-kingdom of Dalriada, the homeland of the Scots on the "Coastland of the Gael" (Argyll). Which would have made him, effectively, Arthur's father. Aedan mac Gabrain, the father of the historical Arthur, did become King of Dalriada in 574. He was renowned for his powerful navy.

Now, let's take this further. In the traditional legend of King Lear, as used by one William Shakespeare, the king has three daughters: Goneril, Regan and Cordelia. During the course of my Arthurian researches, I found three women intimately connected with Arthur's father. They were:

Gwenhwyfar - Arthur's wife (and therefore Aedan's daughter-in-law)

Muirgein - Arthur's half-sister (Aedan's first daughter)

Creiddylad - Arthur's mother (Aedan's lover)

The second of these was not exclusively known as Muirgein. Several of her alternative names derive from rigan, an Early Irish word for a "princess", which obviously developed into the more familiar "Regan". Creiddylad also had other names.

According to the Welsh sources, Arthur's last battle was brought about by a quarrel between two sisters, Gwenhwyfar and Gwenhwyfach. These can be identified as Arthur's wife and his half-sister, Gwenhwyfar ("Goneril") and Muirgein ("Regan"), who did end up on opposing sides.

The Lear legend suggests that two of the King's daughters betrayed him while the third remained constant. In the case of Arthur - or rather, his father - it could be argued that Aedan's two daughters, Gwenhwyfar and Muirgein, brought about the cataclysmic battle which claimed the life of his son, although his lover Creiddylad appears to have played no part in that.

The lovely Creiddylad was essentially subordinate - a "daughter" - to Aedan, the lord of the isles and King of Dalriada. The earlier, pre-Shakespearean versions of the legend have King Lear reunited with his beloved Cordelia after his other two daughters very nearly ruined the kingdom: in fact, Aedan did live for another fourteen unhappy years after the quarrel between his two daughters brought about the death of his son by Creiddylad.

This is a quick summary, of course, but the basics are there: the legend of King Lear and his three daughters corresponds with the historical situation of Aedan, the father of Arthur, who had two squabbling daughters (one being his daughter-in-law) and a third princess, whom he truly loved. The names of Lear's daughters can all be derived from the original princesses in Aedan's immediate family circle, while the name of Lear himself relates to Aedan's role as the lord of the sea.

(While we're on the subject, in Shakespeare's King Lear, Goneril marries the Duke of Albany - another name for Scotland. Regan marries the Duke of Cornwall, a place frequently, and mistakenly, associated with south-west Britain in Arthurian lore - in the book, I explain what "Cornwall" really meant.)

What, then, of Arthur? Well, British - i.e. Welsh - tradition preserves several legends of the Children of Llyr. And in my next blogpost, I'll explain where Arthur fits into that tradition, albeit under another name.

Like a great deal of Arthurian source material, the Lear legend has been ignored or overlooked because, on the face of it, it has nothing whatever to do with Arthur. The problem is one of names.

Historically, names are a problem. Let's take an individual from the lifetime of William Shakespeare. Sir Robert Cecil was the deformed, diminutive son of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, who served as chief minister and adviser to Elizabeth I. Robert succeeded his father, and went on to serve James I. Together, William and Robert Cecil were among the most ruthless and rapacious statesmen this country has ever known.

In 1603, Sir Robert Cecil became Baron Cecil of Essenden. The following year, he was made Viscount Cranborne. The year after that, he was elevated to the earldom of Salisbury. Over a period of just a couple of years, Cecil's name changed more than once. It was proper to refer to him as Lord Cranborne and, later, the Earl of Salisbury.

He also had nicknames, and plenty of them. Robertus Diabolus, the Toad, King James's 'little beagle' ...

Now, if we were to apply the "only one name per historical individual" rule which is routinely applied to Arthurian studies, then Sir Robert Cecil ceased to exist in about 1603 (he actually died in 1612). Out of nowhere appeared another person altogether, known as Salisbury.

And Will Shakespeare, of course, was not indicating Robert Cecil in the impish character of Robin Goodfellow ('Puck') or the malignant and deformed Richard 'Crookback' of Richard III. No way. Shakespeare would never have done such thing (except that he did).

You see the problem? If we insist that everybody in history only ever had the one name, and the one name only, we're not going to make much sense of history, are we? (In The King Arthur Conspiracy I also cite the example of General Schwarzkopf, who commanded the allied forces in the first Gulf War: he was also known as "Stormin' Norman" and "The Bear" - which would appear to have made him three different people.)

The character of Llyr (Irish: Lir) occurs in British tradition. His name meant "Sea". If we approach this character with our modern-day heads on, pretending that everyone throughout history has only ever had one name (so that Margaret Thatcher and the Iron Lady were obviously not the same person), then we are stuck. Who was Llyr, or Lir? No idea. Probably a myth.

Or maybe he was a lord of the sea-kingdom of Dalriada, the homeland of the Scots on the "Coastland of the Gael" (Argyll). Which would have made him, effectively, Arthur's father. Aedan mac Gabrain, the father of the historical Arthur, did become King of Dalriada in 574. He was renowned for his powerful navy.

Now, let's take this further. In the traditional legend of King Lear, as used by one William Shakespeare, the king has three daughters: Goneril, Regan and Cordelia. During the course of my Arthurian researches, I found three women intimately connected with Arthur's father. They were:

Gwenhwyfar - Arthur's wife (and therefore Aedan's daughter-in-law)

Muirgein - Arthur's half-sister (Aedan's first daughter)

Creiddylad - Arthur's mother (Aedan's lover)

The second of these was not exclusively known as Muirgein. Several of her alternative names derive from rigan, an Early Irish word for a "princess", which obviously developed into the more familiar "Regan". Creiddylad also had other names.

According to the Welsh sources, Arthur's last battle was brought about by a quarrel between two sisters, Gwenhwyfar and Gwenhwyfach. These can be identified as Arthur's wife and his half-sister, Gwenhwyfar ("Goneril") and Muirgein ("Regan"), who did end up on opposing sides.

The Lear legend suggests that two of the King's daughters betrayed him while the third remained constant. In the case of Arthur - or rather, his father - it could be argued that Aedan's two daughters, Gwenhwyfar and Muirgein, brought about the cataclysmic battle which claimed the life of his son, although his lover Creiddylad appears to have played no part in that.

The lovely Creiddylad was essentially subordinate - a "daughter" - to Aedan, the lord of the isles and King of Dalriada. The earlier, pre-Shakespearean versions of the legend have King Lear reunited with his beloved Cordelia after his other two daughters very nearly ruined the kingdom: in fact, Aedan did live for another fourteen unhappy years after the quarrel between his two daughters brought about the death of his son by Creiddylad.

This is a quick summary, of course, but the basics are there: the legend of King Lear and his three daughters corresponds with the historical situation of Aedan, the father of Arthur, who had two squabbling daughters (one being his daughter-in-law) and a third princess, whom he truly loved. The names of Lear's daughters can all be derived from the original princesses in Aedan's immediate family circle, while the name of Lear himself relates to Aedan's role as the lord of the sea.

(While we're on the subject, in Shakespeare's King Lear, Goneril marries the Duke of Albany - another name for Scotland. Regan marries the Duke of Cornwall, a place frequently, and mistakenly, associated with south-west Britain in Arthurian lore - in the book, I explain what "Cornwall" really meant.)

What, then, of Arthur? Well, British - i.e. Welsh - tradition preserves several legends of the Children of Llyr. And in my next blogpost, I'll explain where Arthur fits into that tradition, albeit under another name.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)