Just been told that an interview with me is now up on the PaganPages.org website.

So, with thanks to Mabh Savage, I give you ... The Pagan Pages Interview with Author Simon Stirling. I think it's a good one.

Toodle-pip!

The Future of History

Showing posts with label Scotland. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Scotland. Show all posts

Sunday, 2 November 2014

Thursday, 2 October 2014

The Matter of Scotland

The Scottish Statesman, a new online newspaper for Scotland, launched today.

Here's my first contribution. It's about Arthur in Scotland, and the English approach to history.

More news to come ...

Here's my first contribution. It's about Arthur in Scotland, and the English approach to history.

More news to come ...

Wednesday, 27 August 2014

The X Factor

I treated myself, the other day. I bought a copy of Allan Campbell McLean's The Hill of the Red Fox.

It must be 35 years since I borrowed that book from my local library in Birmingham. Time spent on holiday in Scotland had planted a deep-rooted fascination, bordering on thirst, for all things Scottish. The Hill of the Red Fox, which sits comfortably alongside Stevenson's Kidnapped and Buchan's Thirty-Nine Steps, was one of the stories which allowed me to keep in touch, as it were, with western Scotland when I was back home in the West Midlands. It also inspired my interest in the Gaelic language (there is a little glossary of Gaelic terms in the back, and this fascinated me as a kid - the Gaelic has a dignity, a romance, and a connection with nature that English seldom matches). When the chance arose, I opted to take Gaelic Studies at the University of Glasgow, largely because of the glossaries I had previously found in such books as The Hill of the Red Fox.

Rooting around a charity bookshop in Evesham, a day or two after I'd read The Hill of the Red Fox, I came across an old copy of another novel by Allan Campbell McLean. The Year of the Stranger. I'm reading it now.

Like The Hill of the Red Fox, it's set on the Isle of Skye. But whereas the former novel takes place during the Cold War 1950s and involves espionage, murder and nuclear secrets (all grist to my adolescent mill, back in the late 70s), The Year of the Stranger takes place in the Victorian era. And it paints a perfectly clear picture of the gross injustices of aristocratic rule in the Highlands and Islands.

There's a referendum coming up. The people of Scotland have a choice - do they want independence, or are they anxious to remain in the United Kingdom? I don't have a vote, although I wish I did. The vote will take place the day before my 12th wedding anniversary. I married a woman who is half-Scots. We were married on the Isle of Iona. I can think of no more exciting anniversary present than a resounding YES to Scottish independence.

There are many, many reasons why it's a good idea. Some of them are to be found in The Year of the Stranger. It's a reminder that, after the Treaty of Union between England and Scotland in 1707, the people of Scotland pretty much lost every last one of their rights. They were cleared from their native lands, forced out of their homes to make way for sheep (a lucrative business, but one that destroyed the ecology of the Highlands) or simply to provide an absentee landlord and his wealthy friends with even more empty land to call their own. Servile deference was demanded by the anglicised gentry. That deference was not just demanded - it was imposed by force. While the aristocracy turned Scotland into their own exclusive playground, those to whom the land had belonged were shipped off to America, Canada, Australia, in their thousands. Those who remained behind had no choice but to tug their forelocks and grovel to the latest outsider who called himself their landlord. A terrible punishment awaited those who resisted. The fish in the rivers belonged to the aristocracy; the deer on the hills were theirs. They owned - or believed that they owned - everything.

The spirit of the Highlanders was all but broken. Many went off to fight in Britain's wars (sustaining a disproportionate amount of casualties, compared with the rest of the UK). Those at home found themselves oppressed, not just by the aristocrats, who could buy the law, but also by religious extremists, who forced their neighbours into ever more demoralised forms of mental straitjacket. As always, aristocracy and religious zealotry went hand in hand. The once-proud people learned to live in fear of their outlandish landlords and their crazy preachers. They had become little more than slaves.

It took the 20th century to pull Scotland - and the rest of the UK - out of that moral, political and economic insanity. Votes for all, regardless of income and gender; universal education; welfare; healthcare; collective bargaining. Gradually, civilisation dawned. But all that has now been undermined.

Tom Devine, probably the most respected historian in Scotland, explained why it was time to vote YES to independence. The union was of benefit (he feels) from the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 up till the Thatcherite revolution of 1979. But that's when union with England ceased to be of any real advantage to the Scots. The neoliberal agenda being so ruthlessly pursued by successive British governments is nothing more than a determined attempt to turn back the clock. While the stark picture of gross economic, political and legal inequality as presented by Allan Campbell McLean in The Year of the Stranger strikes us today as quaintly barbaric, be in no doubt that to those who currently hold power in Westminster, that sort of rampant injustice makes perfect sense.

Social and economic progress was turned around in 1979. Margaret Thatcher's simplistic economic policies were an absolute disaster - and yet the receipts from (Scottish) North Sea Oil and Gas propped up the nation's finances, so that things didn't look quite as bad as they really were (and there was always the press to mislead us as to what was really going on). But if the natural wealth of Scotland bailed out Thatcher's failed experiments, it was the Scots who paid the greatest price - their industry practically destroyed. Nuclear weapons? The English wouldn't want them anywhere near their coastal towns. Put them within 25 miles of the most densely populated area in Scotland. Oh, and the poll tax that nobody wanted? That was visited on the Scots a full year before they tried it out in England. Scotland's wealth subsidised Westminster, but rather than show the slightest gratitude, Tory commentators chose to brand the Scots "scroungers" and "subsidy-junkies". That is what colonisation looks like.

If Scotland chooses not to free itself of the shackles of aggressive, patronising, condescending, grasping Westminster rule, it will live to regret it. Scotland is one of the richest countries in the world, and yet hundreds of thousands of its children are falling into poverty as a result of Tory ideology (there is only one - ONE - Tory MP in Scotland). A person from Aberdeenshire, when asked to explain why she is voting YES, said, "When I look out to sea, I see nothing but oil-rigs. When I look inland, I see nothing but food-banks."

And that, folks, is your warning. History is repeating itself. A corrupt and self-serving aristocracy is seeking to take us back to those dark days in which we all had to doff our caps to the idiots who lorded it over us; that, or we starved. They could take our homes, throw us out into the cold, send us overseas, deny us our rights and use lethal force against us. Their obscene wealth was stolen from the millions who actually earned it.

England can, if it chooses, wrap itself up in the Downton Abbey lies about the past and carry on down the road towards government by half-baked toffs and their vicious minions, or the only apparent alternative, which is arse-about-face UKIP-style fascism. But if the Scots want to avoid the iniquities of history being revisited upon them, they need to take the chance that is now on offer.

For one thing is clear. Those who cling to the idea of the union do so for one of two reasons.

The first is that they are the very aristocrats who believe that they own Scotland (and its people, and its natural resources) and who insist on maintaining their privileges, no matter what it takes.

The other is that they have some vague hope that somehow, the Scots and the English and the Welsh and the people of Northern Ireland will someday turn the neoliberal juggernaut around and get us back on the road to democracy and decency. But that ain't gonna happen. The English are too busy blaming everybody else in the world for their mistakes to wake up to the very real trouble they're in. The Scots are already awake. The YES campaign is by far the biggest, broadest, most inclusive and engaged grassroots campaign I've ever seen: a genuine movement of the people. It's not about nationalism. It's about reality. They know that the union is finished, and that Thatcherism killed it. They see democracy slipping ever further and further away, as the gentry comes marching back to lay claim to what it never earned. The NO campaign has behaved as the defenders of privilege always do: telling lies about what is in the people's best interests and issuing one threat after another. A conniving minority is also out there, doing the gentry's dirty work, like the hated factors of old.

There's still time to read The Year of the Stranger before the referendum. Which means there's still a chance to remind ourselves what rule by those-who-believe-they're-born-to-rule tends to mean. It wasn't always thus in the Highlands and Islands. But the Treaty of Union imposed the worst kind of patrician government-by-force on a proud and independent-minded people, and those people were worn down, beaten, cheated by magistrates, bullied by a greedy gentry and terrorised by paranoid ministers.

And that's where we're heading again, unless the Scots display their natural courage, intelligence and sense of social justice, and set themselves free. It only takes an 'X' in a box to rid the land of the fear of the landlord and his factor, and to show the world the way forward again.

Alba gu brath!!

It must be 35 years since I borrowed that book from my local library in Birmingham. Time spent on holiday in Scotland had planted a deep-rooted fascination, bordering on thirst, for all things Scottish. The Hill of the Red Fox, which sits comfortably alongside Stevenson's Kidnapped and Buchan's Thirty-Nine Steps, was one of the stories which allowed me to keep in touch, as it were, with western Scotland when I was back home in the West Midlands. It also inspired my interest in the Gaelic language (there is a little glossary of Gaelic terms in the back, and this fascinated me as a kid - the Gaelic has a dignity, a romance, and a connection with nature that English seldom matches). When the chance arose, I opted to take Gaelic Studies at the University of Glasgow, largely because of the glossaries I had previously found in such books as The Hill of the Red Fox.

Rooting around a charity bookshop in Evesham, a day or two after I'd read The Hill of the Red Fox, I came across an old copy of another novel by Allan Campbell McLean. The Year of the Stranger. I'm reading it now.

Like The Hill of the Red Fox, it's set on the Isle of Skye. But whereas the former novel takes place during the Cold War 1950s and involves espionage, murder and nuclear secrets (all grist to my adolescent mill, back in the late 70s), The Year of the Stranger takes place in the Victorian era. And it paints a perfectly clear picture of the gross injustices of aristocratic rule in the Highlands and Islands.

There's a referendum coming up. The people of Scotland have a choice - do they want independence, or are they anxious to remain in the United Kingdom? I don't have a vote, although I wish I did. The vote will take place the day before my 12th wedding anniversary. I married a woman who is half-Scots. We were married on the Isle of Iona. I can think of no more exciting anniversary present than a resounding YES to Scottish independence.

There are many, many reasons why it's a good idea. Some of them are to be found in The Year of the Stranger. It's a reminder that, after the Treaty of Union between England and Scotland in 1707, the people of Scotland pretty much lost every last one of their rights. They were cleared from their native lands, forced out of their homes to make way for sheep (a lucrative business, but one that destroyed the ecology of the Highlands) or simply to provide an absentee landlord and his wealthy friends with even more empty land to call their own. Servile deference was demanded by the anglicised gentry. That deference was not just demanded - it was imposed by force. While the aristocracy turned Scotland into their own exclusive playground, those to whom the land had belonged were shipped off to America, Canada, Australia, in their thousands. Those who remained behind had no choice but to tug their forelocks and grovel to the latest outsider who called himself their landlord. A terrible punishment awaited those who resisted. The fish in the rivers belonged to the aristocracy; the deer on the hills were theirs. They owned - or believed that they owned - everything.

The spirit of the Highlanders was all but broken. Many went off to fight in Britain's wars (sustaining a disproportionate amount of casualties, compared with the rest of the UK). Those at home found themselves oppressed, not just by the aristocrats, who could buy the law, but also by religious extremists, who forced their neighbours into ever more demoralised forms of mental straitjacket. As always, aristocracy and religious zealotry went hand in hand. The once-proud people learned to live in fear of their outlandish landlords and their crazy preachers. They had become little more than slaves.

It took the 20th century to pull Scotland - and the rest of the UK - out of that moral, political and economic insanity. Votes for all, regardless of income and gender; universal education; welfare; healthcare; collective bargaining. Gradually, civilisation dawned. But all that has now been undermined.

Tom Devine, probably the most respected historian in Scotland, explained why it was time to vote YES to independence. The union was of benefit (he feels) from the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 up till the Thatcherite revolution of 1979. But that's when union with England ceased to be of any real advantage to the Scots. The neoliberal agenda being so ruthlessly pursued by successive British governments is nothing more than a determined attempt to turn back the clock. While the stark picture of gross economic, political and legal inequality as presented by Allan Campbell McLean in The Year of the Stranger strikes us today as quaintly barbaric, be in no doubt that to those who currently hold power in Westminster, that sort of rampant injustice makes perfect sense.

Social and economic progress was turned around in 1979. Margaret Thatcher's simplistic economic policies were an absolute disaster - and yet the receipts from (Scottish) North Sea Oil and Gas propped up the nation's finances, so that things didn't look quite as bad as they really were (and there was always the press to mislead us as to what was really going on). But if the natural wealth of Scotland bailed out Thatcher's failed experiments, it was the Scots who paid the greatest price - their industry practically destroyed. Nuclear weapons? The English wouldn't want them anywhere near their coastal towns. Put them within 25 miles of the most densely populated area in Scotland. Oh, and the poll tax that nobody wanted? That was visited on the Scots a full year before they tried it out in England. Scotland's wealth subsidised Westminster, but rather than show the slightest gratitude, Tory commentators chose to brand the Scots "scroungers" and "subsidy-junkies". That is what colonisation looks like.

If Scotland chooses not to free itself of the shackles of aggressive, patronising, condescending, grasping Westminster rule, it will live to regret it. Scotland is one of the richest countries in the world, and yet hundreds of thousands of its children are falling into poverty as a result of Tory ideology (there is only one - ONE - Tory MP in Scotland). A person from Aberdeenshire, when asked to explain why she is voting YES, said, "When I look out to sea, I see nothing but oil-rigs. When I look inland, I see nothing but food-banks."

And that, folks, is your warning. History is repeating itself. A corrupt and self-serving aristocracy is seeking to take us back to those dark days in which we all had to doff our caps to the idiots who lorded it over us; that, or we starved. They could take our homes, throw us out into the cold, send us overseas, deny us our rights and use lethal force against us. Their obscene wealth was stolen from the millions who actually earned it.

England can, if it chooses, wrap itself up in the Downton Abbey lies about the past and carry on down the road towards government by half-baked toffs and their vicious minions, or the only apparent alternative, which is arse-about-face UKIP-style fascism. But if the Scots want to avoid the iniquities of history being revisited upon them, they need to take the chance that is now on offer.

For one thing is clear. Those who cling to the idea of the union do so for one of two reasons.

The first is that they are the very aristocrats who believe that they own Scotland (and its people, and its natural resources) and who insist on maintaining their privileges, no matter what it takes.

The other is that they have some vague hope that somehow, the Scots and the English and the Welsh and the people of Northern Ireland will someday turn the neoliberal juggernaut around and get us back on the road to democracy and decency. But that ain't gonna happen. The English are too busy blaming everybody else in the world for their mistakes to wake up to the very real trouble they're in. The Scots are already awake. The YES campaign is by far the biggest, broadest, most inclusive and engaged grassroots campaign I've ever seen: a genuine movement of the people. It's not about nationalism. It's about reality. They know that the union is finished, and that Thatcherism killed it. They see democracy slipping ever further and further away, as the gentry comes marching back to lay claim to what it never earned. The NO campaign has behaved as the defenders of privilege always do: telling lies about what is in the people's best interests and issuing one threat after another. A conniving minority is also out there, doing the gentry's dirty work, like the hated factors of old.

There's still time to read The Year of the Stranger before the referendum. Which means there's still a chance to remind ourselves what rule by those-who-believe-they're-born-to-rule tends to mean. It wasn't always thus in the Highlands and Islands. But the Treaty of Union imposed the worst kind of patrician government-by-force on a proud and independent-minded people, and those people were worn down, beaten, cheated by magistrates, bullied by a greedy gentry and terrorised by paranoid ministers.

And that's where we're heading again, unless the Scots display their natural courage, intelligence and sense of social justice, and set themselves free. It only takes an 'X' in a box to rid the land of the fear of the landlord and his factor, and to show the world the way forward again.

Alba gu brath!!

Sunday, 17 August 2014

Alyth, the Scene of Arthur's Last Battle

While I work on Shakespeare's Son - my biography of Sir William Davenant, a man of whom I'm becoming increasingly fond - The Grail continues to make its way through the publishing process, courtesy of Moon Books. So, by way of a sneak preview, in this post I shall offer up some of the evidence for the location of Arthur's last battle.

The Battle of Circenn

You probably think Arthur's last battle was fought at a place called "Camlann". I've been unable to find any reference to that place-name before the Middle Ages. The very earliest mentions of anyone called Arthur in the records indicate that he died in a battle fought in Angus, Scotland.

Adomnan of Iona's Life of Columba (circa 697) tells us that Artur son of Aedan was present when his father was "ordained" king of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574. The saint predicted the fates of Aedan's sons, announcing that Artur would "fall in battle, slain by enemies". Adomnan assured his readers that this prophecy came true when Artur and at least one of his brothers was killed in a "battle of the Miathi".

The Miathi, or Maeatae, were a Pictish tribe: essentially, they held the low-lying lands to the south and east of the Highland massif. Another Latinate term for these people was Verturiones.

The Irish annals, which drew at least some of their information from the records kept by Columba's monks on the Isle of Iona, specify that Artur son of Aedan died in a "battle of Circenn". This refers to the Pictish province which was roughly contiguous with today's Angus and the Mearns. The term Circenn combined the Gaelic cir, meaning a "comb" or "crest", and cenn, "heads". Circenn, then, was the land of the Comb-heads. This tells us that the Miathi Picts modelled their appearance on their totem beast, the boar (rather like their compatriots in the Orkneys, the Orcoi, from orc - a young boar). Indeed, it is possible that the Latinate name for the Verturiones tribe combines verres and turio and indicates the "offshoots" or "offspring" of the "boar", while the very term "Pict" (variant, "Pecti", "Pecht") quite possibly derived from the Latin pecten, a "comb".

Now, let's look at "Camlann" - the traditional name for Arthur's last battle. Its first appearance in the records comes in an entry interpolated into the Welsh Annals, where it refers to a gueith cam lann or "strife of cam lann". By the time this came to be written down, the region in which Artur son of Aedan died was speaking a version of Northumbrian Old English which became the dialect known as Lowland Scots. In that dialect, cam lann would mean "comb land".

In other words, "Camlann" is merely an anglicised version of the Gaelic Circenn, the land of the "Comb-heads" in which the first Arthur on record fell in a cataclysmic battle.

Culhwch and Olwen

One of the oldest of the Welsh (i.e. British) tales to feature Arthur is that of Culhwch ac Olwen. It forms a sort of mythologised, potted account of Arthur's career, culminating in the desperate and bloody hunt for a king who - for his sins - was turned into a boar. This hunt begins with a violent amphibious landing, at a site which can be identified as Cruden Bay, on the Aberdeenshire coast, after which Arthur is met by the "saints of Ireland" who "besought his protection". The dreadful Boar-King is challenged and chased from Esgeir Oerfel, the "Cold Ridge" of the Grampians, the Boar-King making his way across country towards Llwch Tawy (Loch Tay) before he is intercepted by Arthur and his men and driven into a river.

In The King Arthur Conspiracy I identified the treacherous Boar-King as Morgan the Wealthy, a renegade British prince who abducted Arthur's wife, Gwenhwyfar, and escaped into the land of the Miathi Picts (his bolt hole appears to have been the fortified Hill of Tillymorgan in Strathbogie). The site where Morgan finally came to grief is marked by the "Morganstone" on the west bank of the River Ericht, a short distance to the west of the Hill of Alyth in the great vale of Strathmore in Angus.

Arthurian Connections with Alyth

Before we proceed, let us consider some ancient references to Arthur and his family in the context of Alyth and its immediate vicinity.

In addition to having a son named Artur or Artuir, King Aedan of the Scots had a daughter called Muirgein. According to Whitley Stokes, editing and translating the Martyrology of a 9th-century Irish monk called Oengus, Muirgein daughter of Aedan was born "in Bealach Gabrain".

The inability of certain scholars to find a "Bealach Gabrain" in Scotland has led some to argue that Muirgein daughter of Aedan was utterly unconnected with Artur son of Aedan. But place-names evolve. The Gaelic term bealach, meaning a "pass" or "gorge", usually appears as "Balloch" on today's maps. There is a "Balloch" which runs along the feet of Barry Hill and the adjacent Hill of Alyth in Strathmore.

Furthermore, this "Balloch" or bealach was in a region named after the grandfather of Artur and Muirgein. Gabran was the father of Aedan. He ruled the Scots for twenty years until his death in about AD 559 and gave his name to the region of Gowrie (a corruption of Gabran). The "Balloch" near Alyth was in Gabran's land (Gabrain) and lies close to the town of Blairgowrie, which also recalls the name of Arthur's grandfather. The "Balloch" at the foot of the Hill of Alyth was almost certainly the "Bealach Gabrain" or "pass of Gowrie" where Arthur's (half-)sister, Muirgein daughter of Aedan mac Gabrain, was born. To pretend that the Balloch of Gowrie could not have been "Bealach Gabrain" because they are not spelled the same way these days is tantamount to claiming that Londinium and London could not have been the same place.

So Arthur's sister, Muirgein (latterly, Morgan le Fay), was born near Alyth. Writing in about 1527, the Scottish historian Hector Boece also indicated that Arthur's wife was buried at Meigle, which is just a mile or two south of Alyth. Hector Boece's local tradition recalled Gwenhwyfar as Vanora (via Guanora) and claimed that she had been held hostage in the Iron Age hill-fort atop Barry Hill, adjacent to the Hill of Alyth, before she was executed and buried in what is now the kirkyard at Meigle. A carved Pictish standing stone, now on display at the Meigle museum, reputedly depicts the execution or burial of Arthur's wife.

Y Gododdin

One of the best sources of information about Arthur's last battle is the ancient epic, Y Gododdin. This was composed and sung by Aneirin, a British bard of the Old North, and can be dated to circa AD 600 (the date of Arthur's last battle is given in the Irish annals as, variously, AD 594 and 596).

Unfortunately, the relevance of Aneirin's elegiac tribute to the warriors of Lothian (the "Gododdin") has been missed by scholars who want to believe that the poem bemoans the destruction of a British war-band from the Edinburgh area which had the misfortune to be wiped out at a mythical battle fought at Catterick in North Yorkshire. No evidence exists that any such battle was fought. The Angles (forerunners of the English) preferred not to recollect their defeats but were happy to remember, and to boast about, their victories. If the Angles of Northumbria had indeed obliterated a British band of heroes from Lothian at Catterick, we might assume that they would have remembered doing so. And no scholar has yet explained the presence of "Irishman and Picts" at this imaginary battle in Anglian territory.

A verse or two of Y G[ododdin, added at a later date than the original composition, described a battle fought in Scotland (Strathcarron) in AD 642 and the death in that battle of a Scottish king who just happened to be a nephew of Artur son of Aedan. This interpolation does at least suggest that the subject of the original poem was a battle fought in roughly the same area (Scotland) by the family of Artur and his father Aedan. The Y Gododdin poem also mentions various famous warriors who appear in the early accounts of Arthur's career and who were contemporary with Artur son of Aedan.

One surviving version of Y Gododdin even mentions Artur/Artuir by name:

Gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef Arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

Confused by the misidentification of the battle sung about by Aneirin in Y Gododdin, and the assumption that Arthur himself could not have been present at that battle, scholars have persistently mistranslated this verse - mostly in an attempt to render the second half of the second line, "He was no Arthur". But Aneirin's verse should properly be translated thus:

Black ravens [warriors] sang in praise of the hero [Welsh, arwr]

of Circenn [transliterated into Welsh as "caer ceni"]. He blamed Arthur;

the dogs cursed in return for our wailing/lamentation ...

Aneirin indicated, in his Y Gododdin elegy, precisely where the final battle took place:

Eil with gwelydeint amallet

y gat veirch ae seirch greulet

bit en anysgoget bit get ...

Which translates as:

Again they came into view around the alled,

the battle-horses and the bloody armour,

still steadfast, still united ...

The "alled" was Aneirin's Welsh-language attempt at the Gaelic Allaid - also Ailt - or the Hill of Alyth.

Breuddwyd Rhonabwy

The extraordinary medieval Welsh tale of The Dream of Rhonabwy actually provides a description of the scene in the hours before Arthur's last battle was fought. The visionary seer, Rhonabwy, finds himself crossing a great plain with a river running through it (Strathmore). He is met by a character call Iddog, "Churn of Britain", who admits that it was he who caused the cataclysmic "battle of Camlan" by betraying Arthur. In company with Iddog, Rhonabwy approaches the "Ford of the Cross" (Rhyd-y-Groes) on the river. A great army is encamped on either side of the road and Arthur is seated on a little flat islet in the river, beside the ford.

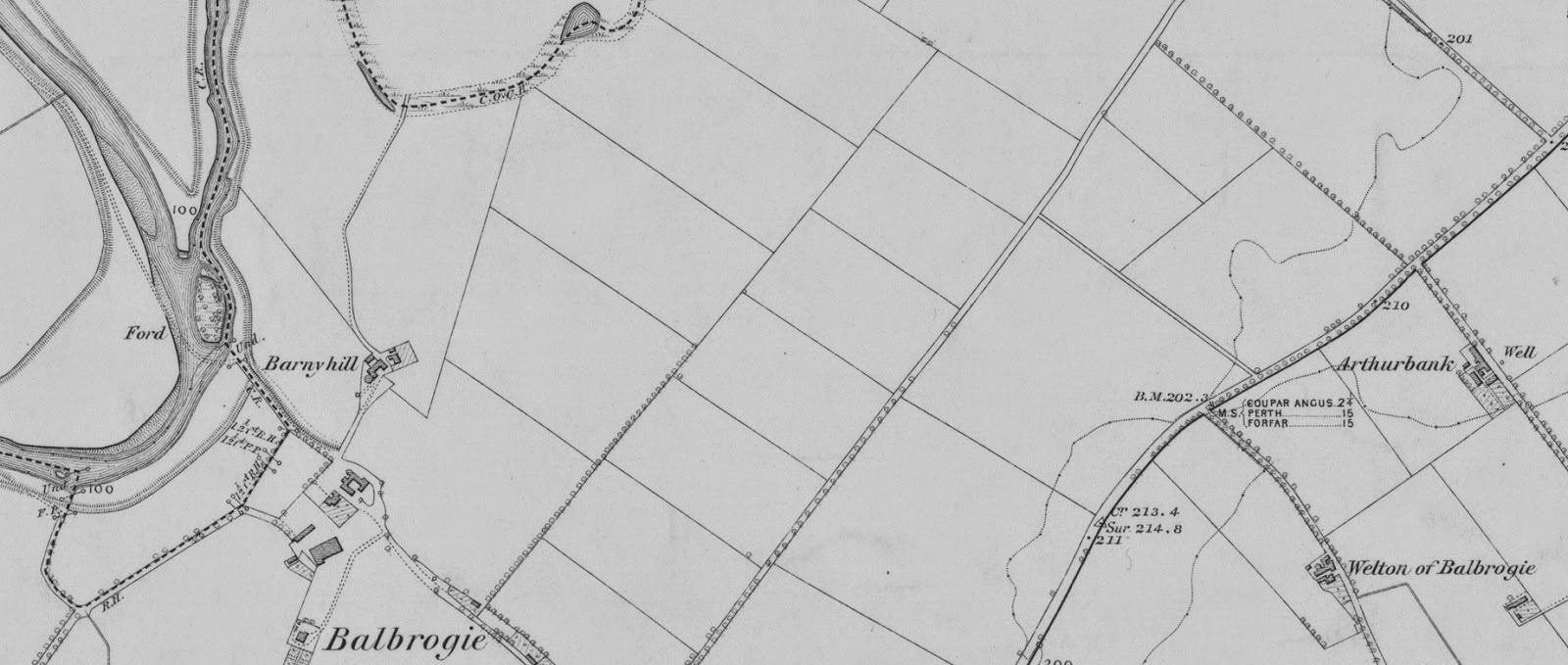

The topography precisely matches the detail from a 19th-century Ordnance Survey map of the area around Alyth seen at the top of this post. On the right-hand side of the detail is the ridge known as Arthurbank, which lies along the River Isla, opposite the junction of the River Ericht with the River Isla (a few miles down the Ericht from the site of the Morganstone). A little flat islet lies in the River Isla, close to the Arthurbank shore, and a ford runs alongside this little islet, exactly as described in the Welsh account of Rhonabwy's dream.

Aneirin also mentioned this ford in his Y Gododdin poem as rhyd benclwyd - the "ford" of the "grey" or "holy mount". There is, indeed, a Greymount marked on the map, a short distance to the north of the ford on the Isla. In his Agriculture of Perthshire, published in 1799, the Rev. Dr Robertson described the discovery of a "large Druidical temple" at Coupar Grange, adjacent to this ford. A standing stone found in this "temple" would no doubt have been rebranded a "cross" by the early Christians, so that the ford across the Isla, beside the little flat islet, would have become known as the Ford of the Cross (Rhyd-y-Groes), as described in The Dream of Rhonabwy, or the "Ford of the Grey/Holy Mount" (rhyd benclwyd) as described by Aneirin.

Until the late 18th century, an Arthurstone stood at the south-eastern edge of the Arthurbank ridge (its presence is still marked on the map). This Arthurstone corresponds to the Morganstone, a few miles away up the River Ericht, and marks the spot where Arthur fell in his battle with the Boar-King of the Miathi Picts in the land of the "crested" Comb-heads, Camlann.

The Head of the Valley of Sorrow

After the battle, Arthur's wife Gwenhwyfar was executed and buried only a mile or so away at Meigle. The legend of Culhwch and Olwen (which, interestingly, features a treacherous individual identified as Grugyn, who also appears in Aneirin's Y Gododdin) tells us that, after the battle at the river with the dangerous Boar-King, Arthur and his heroes once more "set out for the North" to overcome a fearsome witch. She was found inside a cave at Penn Nant Gofid - the "Head of the Valley of Sorrow"- on "the confines of Hell" (which we can interpret as the edge of the territory controlled by those boar-like Miathi Picts). The Welsh gofid ("sorrow/trouble/affiction/grief") appears to have been something of a pun, for another Welsh word for sorrow or grief is alaeth (compare Ailt, Allaid and Alyth, the "Head of the Valley of Alyth" being the very hill on which Arthur's wife is rumoured to have been held prisoner before her execution and burial nearby at Meigle).

In the Welsh tale, this witch is known as Orddu (that is, Gorddu - "Very Black"). A similar legend from the Isle of Mull, whose Arthurian associations have been overlooked for far too long, names the troublesome wife as Corr-dhu ("Black-Crane").

We might also note that the 9th-century Welsh monk known as Nennius described a "wonder" of Scotland in the form of "a valley in Angus, in which shouting is heard every Monday night; Glend Ailbe is its name, and it is not known who makes this noise."

Nennius's Glend Ailbe seems to be a corruption of the Gaelic word for a valley (glen) and the River Isla, or perhaps the Allaid or Hill of Alyth, which dominates the vale of Strathmore. The mysterious shouting in this "Valley of Sorrow" was reputedly heard ever Monday night. And we know from Aneirin's eye-witness account of Arthur's last battle that it came to an end on a Monday.

This is just some of the evidence for Arthur having fallen in the vicinity of Alyth. There is plenty more to come in The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - including descriptions of the Pictish symbol stones, found close to the site of that battle, which actually depict the Grail in use!

I'll let you know when the book is about to be published.

Monday, 2 June 2014

The Meaning of "Camlann"

I received a message from Moon Books today, telling me that the copyedited manuscript of The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion is ready for me to check.

It seems unlikely that the book will be available before the Scottish independence referendum in September. I'll be keeping a close eye on the referendum: the vote takes place the day before my 12th wedding anniversary, and having got married on the Isle of Iona to a woman who is half-Scottish, as well as having gone to university in Glasgow, my sympathies lie very much with the "YES" campaign.

I was also interested to note that Le Monde published this piece, indicating that the pro-independence campaign is gaining ground. The reporter had been in Alyth, Perthshire, to follow the debate. Alyth, as I revealed in The King Arthur Conspiracy, is where Arthur fought his last battle.

How do I know this? Lots of reasons, not least of all the fact that the place is name checked in a contemporary poem of the battle.

But wasn't Arthur's last battle fought at a place called Camlan?

Well, for a long while I wasn't so sure. Now, though, I know that it was - sort of - and I explain why in my forthcoming book on The Grail. But as that may not be out before the referendum, I hereby present this information as a gift to the "YES" campaign and in honour of a warrior who gave his life fighting for Scottish (and British) independence.

Many commentators refuse to accept that the place-name "Camlan" isn't Welsh. The fact that Camlan is the Gaelic name for the old Roman fortifications at Camelon, near Falkirk in central Scotland, means nothing to them. Arthur's "Camlan" was Welsh, and that's all it could have been.

Very silly - and utterly useless, in terms of trying to track down the site of that all-important battle. If it was a Welsh place-name, it would have meant something like "Crooked Valley", which really doesn't help us very much.

The first literary reference to "Camlann" comes in the Annales Cambriae ("Welsh Annals") which mention Gueith cam lann - the "Strife of Camlann". However, that reference cannot be traced back to an earlier date than the 10th century, hundreds of years after the time of Arthur. The contemporary sources make no mention of "Camlann", and so it may be that the name didn't come into use until many years after Arthur's last battle was fought there.

The earliest literary reference to anyone called Arthur concerns an individual named Artur mac Aedain. He was a son of Aedan mac Gabrain, who was "ordained" King of the Scots by St Columba in 574. Accounts of the ordination ceremony indicate that Arthur son of Aedan was present on that occasion, and that St Columba predicted that Arthur would not succeed his father to the Scottish throne but would "fall in battle, slain by enemies."

Those same accounts tell us that Columba's prophecy came true: Artur mac Aedain died in a "battle of the Miathi", which means that he was killed fighting the Picts of central Scotland.

The Irish Annals, which were compiled from notes made by the monks of Iona, inform us that the first recorded Arthur was killed in a "battle of Circenn", fought in about 594. Circenn was the Pictish province immediately to the north of the Tay estuary - broadly, Angus and the Mearns - which was indeed the territory of the "Miathi".

Circenn might have been Pictish territory, but the name of the province is Gaelic. It combines the word cir (meaning a "comb" or a "crest") and cenn, the genitive plural of a Gaelic noun meaning "head". An appropriate translation of Circenn would therefore be "Comb-heads".

The Miathi Picts, like their compatriots in the Orkneys, appear to have modelled their appearance on their totem animal, the boar. This meant that they shaved their heads in imitation of the boar's comb or crest - rather like the Mohawk tonsure, which we wrongly think of as a "Mohican". Indeed, whilst we assume that the term "Pict" derived from the Latin picti, meaning "painted" or "tattooed", there are grounds for suspecting that it was actually a corruption of pecten, the Latin for a "comb" (hence the Old Scots word Pecht, meaning "Pict").

So where does "Camlann" fit into all this?

After Arthur's death, much of southern and central Scotland was invaded by the Angles, those forerunners of the English. As a consequence, the Germanic language known as Northumbrian Old English was established in southern and central Scotland by the 7th century. It eventually became the dialect called Lowland Scots.

In the Scots dialect, came, kem and camb all meant "comb". And lan', laan and lann all meant "land".

The land in which Arthur's last battle had been fought - that is, the Pictish province of Angus - was soon speaking an early variant of the English language, or Lowland Scots. The fact that the Pictish province of Circenn was named after its "Comb-heads", those Miathi warriors who cut their hair to resemble a boar's comb or crest, meant that the place became known by its early English equivalent: "Comb-land" or Camlann.

This was not, of course, the name that Arthur and his warrior-poets would have used for the place. But then, the term "Camlann" didn't appear in any literary source for at least another three or four hundred years. By the time the Welsh annalist came to interpolate the "Camlann" entry into the Annales Cambriae, the location had become known by its Old English/Lowland Scots name. But that name was merely a variant of the older Gaelic name for the province - Circenn, or "Comb-heads".

And that is where the first recorded Arthur fell in battle, as St Columba had predicted. Not in England or Wales or Brittany, but in Angus in Scotland.

The province of the Pictish "Comb-heads". The region known as "Comb-land", cam lann.

It seems unlikely that the book will be available before the Scottish independence referendum in September. I'll be keeping a close eye on the referendum: the vote takes place the day before my 12th wedding anniversary, and having got married on the Isle of Iona to a woman who is half-Scottish, as well as having gone to university in Glasgow, my sympathies lie very much with the "YES" campaign.

I was also interested to note that Le Monde published this piece, indicating that the pro-independence campaign is gaining ground. The reporter had been in Alyth, Perthshire, to follow the debate. Alyth, as I revealed in The King Arthur Conspiracy, is where Arthur fought his last battle.

How do I know this? Lots of reasons, not least of all the fact that the place is name checked in a contemporary poem of the battle.

But wasn't Arthur's last battle fought at a place called Camlan?

Well, for a long while I wasn't so sure. Now, though, I know that it was - sort of - and I explain why in my forthcoming book on The Grail. But as that may not be out before the referendum, I hereby present this information as a gift to the "YES" campaign and in honour of a warrior who gave his life fighting for Scottish (and British) independence.

Many commentators refuse to accept that the place-name "Camlan" isn't Welsh. The fact that Camlan is the Gaelic name for the old Roman fortifications at Camelon, near Falkirk in central Scotland, means nothing to them. Arthur's "Camlan" was Welsh, and that's all it could have been.

Very silly - and utterly useless, in terms of trying to track down the site of that all-important battle. If it was a Welsh place-name, it would have meant something like "Crooked Valley", which really doesn't help us very much.

The first literary reference to "Camlann" comes in the Annales Cambriae ("Welsh Annals") which mention Gueith cam lann - the "Strife of Camlann". However, that reference cannot be traced back to an earlier date than the 10th century, hundreds of years after the time of Arthur. The contemporary sources make no mention of "Camlann", and so it may be that the name didn't come into use until many years after Arthur's last battle was fought there.

The earliest literary reference to anyone called Arthur concerns an individual named Artur mac Aedain. He was a son of Aedan mac Gabrain, who was "ordained" King of the Scots by St Columba in 574. Accounts of the ordination ceremony indicate that Arthur son of Aedan was present on that occasion, and that St Columba predicted that Arthur would not succeed his father to the Scottish throne but would "fall in battle, slain by enemies."

Those same accounts tell us that Columba's prophecy came true: Artur mac Aedain died in a "battle of the Miathi", which means that he was killed fighting the Picts of central Scotland.

The Irish Annals, which were compiled from notes made by the monks of Iona, inform us that the first recorded Arthur was killed in a "battle of Circenn", fought in about 594. Circenn was the Pictish province immediately to the north of the Tay estuary - broadly, Angus and the Mearns - which was indeed the territory of the "Miathi".

Circenn might have been Pictish territory, but the name of the province is Gaelic. It combines the word cir (meaning a "comb" or a "crest") and cenn, the genitive plural of a Gaelic noun meaning "head". An appropriate translation of Circenn would therefore be "Comb-heads".

The Miathi Picts, like their compatriots in the Orkneys, appear to have modelled their appearance on their totem animal, the boar. This meant that they shaved their heads in imitation of the boar's comb or crest - rather like the Mohawk tonsure, which we wrongly think of as a "Mohican". Indeed, whilst we assume that the term "Pict" derived from the Latin picti, meaning "painted" or "tattooed", there are grounds for suspecting that it was actually a corruption of pecten, the Latin for a "comb" (hence the Old Scots word Pecht, meaning "Pict").

So where does "Camlann" fit into all this?

After Arthur's death, much of southern and central Scotland was invaded by the Angles, those forerunners of the English. As a consequence, the Germanic language known as Northumbrian Old English was established in southern and central Scotland by the 7th century. It eventually became the dialect called Lowland Scots.

In the Scots dialect, came, kem and camb all meant "comb". And lan', laan and lann all meant "land".

The land in which Arthur's last battle had been fought - that is, the Pictish province of Angus - was soon speaking an early variant of the English language, or Lowland Scots. The fact that the Pictish province of Circenn was named after its "Comb-heads", those Miathi warriors who cut their hair to resemble a boar's comb or crest, meant that the place became known by its early English equivalent: "Comb-land" or Camlann.

This was not, of course, the name that Arthur and his warrior-poets would have used for the place. But then, the term "Camlann" didn't appear in any literary source for at least another three or four hundred years. By the time the Welsh annalist came to interpolate the "Camlann" entry into the Annales Cambriae, the location had become known by its Old English/Lowland Scots name. But that name was merely a variant of the older Gaelic name for the province - Circenn, or "Comb-heads".

And that is where the first recorded Arthur fell in battle, as St Columba had predicted. Not in England or Wales or Brittany, but in Angus in Scotland.

The province of the Pictish "Comb-heads". The region known as "Comb-land", cam lann.

Friday, 10 January 2014

A Race Against Time

I came across this press piece a few days ago. It's maybe not quite as bad as it first appears: nobody seems to be suggesting that we build new houses on top of the Old Oswestry hill-fort, only on the fields immediately adjacent. But what I found most interesting about the article is what it says of the 3,000 year old hill-fort - that Old Oswestry is "said to be the birthplace of Guinevere, King Arthur's Queen."Ooops, let's back up a bit there. "Guinevere" is a medieval invention. Or, rather, it's a Medieval French rendition of a Welsh name - Gwenhwyfar. It's just one of those Arthurian anomalies that we keep referring to the original characters by the wrong names. Forget Guinevere: she didn't exist. Let's call her Gwenhwyfar instead.

And while we're at it, let's stop saying "King Arthur", because he didn't exist either. His people remembered him as "the emperor Arthur". Or we could just call him "Arthur". But "King Arthur" is purely mythical, even though Arthur himself was real.

Anyway, there is a tradition - apparently - that Gwenhwyfar, the wife of Arthur the Emperor, was born at Old Oswestry. I was quite thrilled to read that, because in "The King Arthur Conspiracy" I endeavoured to trace Gwenhwyfar's family background, and was able to pin it down to the Flintshire region of North Wales. Oswestry, on the Welsh border, is just to the south of that part of the world, and was quite possibly part of the sub-kingdom ruled by Gwenhwyfar's father.

I identified Gwenhwyfar's father as Caradog Freichfras ("Strong-Arm"), who was initially associated with the kingdom of Glywysing, immediately to the south of Oswestry. However, along with a number of other Arthurian heroes, Caradog seems to have shifted his base of operations northwards, initially to the Tegeingl sub-kingdom of Gwynedd, immediately to the north of (and possibly incorporating) Oswestry.

The Iron Age hill-fort believed to have been Gwenhwyfar's birthplace is also pretty close to the parish of Llangollen. This was home to an individual who became known as St Collen, although I argue that he was better known as (St) Cadog - another princeling of South Wales who moved, first into North Wales and, later, into central Scotland. Cadog - or Collen - appears to have functioned as a foster-father figure to Gwenhwyfar, or perhaps as the Druidic leader of her maidenly cult, and it is rather telling to discover that a Croes Gwenhwyfar - "Gwenhwyfar's Cross" - exists at Llangollen.

In other words, there is a fair amount of evidence which places the young Gwenhwyfar in the general area of Oswestry - before she, like so many of the others, moved north into what is now Scotland - and so we cannot write off the possibility that she was indeed born in the Iron Age hill-fort of Old Oswestry.

But that's not really the point of this post. Neither, for that matter, is any hand-wringing or soul-searching over the desirability of a new housing estate next door to Gwenhwyfar's birthplace - although that issue might serve as a sort of metaphor for what this post is all about.

It's about the race against time that we're currently in. Let me explain:

We live in unprecendented times. The internet, for example, is like nothing humanity that has ever known. So much knowledge at our fingertips! Researching Arthur and his people - and, for example, narrowing down the location of his last battle, as I did in The King Arthur Conspiracy and, in more detail, in my forthcoming The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - would have been immensely more time-consuming and expensive than it was.

However ... we also live in precedented times. I again cover this in The Grail, which is very much an exploration of the three "ages" of civilisation. We are currently being bullied out of the "Human age", which is characterised by liberal democracy and scientific materialism, by a resurgence of medieval "Heroic age" values, which we can characterise as dominated by religious fanaticism and extreme social inequality. This regression - the determination of some to tug us back into the kind of society which existed during the Middle Ages - is not really possible. It will lead (inevitably, I believe) to the collapse of our civilisation.

The internet is a fascinating product of our times. It is, in many ways, the ultimate "Human age" invention - possible only because of the technological infrastructure that was created by science, and thoroughly democratic, in that it is available to anybody. But the infrastructure necessary for the maintenance of a viable internet might not survive for long, and the anti-democratic instincts of those religious and political extremists who are forcing us back towards the "Heroic age" of times past are unlikely to favour the internet in its current form (although the internet is also one of the great purveyors of "Heroic age" thought, as uninformed opinion usurps the place of evidence-based logical reasoning and hysterical, paranoid memes spread like wildfire).

So, those of us who are fortunate enough to have access to the Global City which is the internet should really be using it to the best of our abilities. When it goes, it's gone - and our descendants will wonder at the race of supermen who could communicate instantaneously with millions across great distances, and who could access any information they required, just like that.

Do you really want your great-grandchildren to know that you had access to the greatest library the world has ever known, and the ability to exchange information with a massive global community - and all you did was post pictures of cats?

One of the ways in which the "Heroic age" is fighting back is through the rewriting of history. Michael Gove's cretinously empty-headed intervention in the matter of the First World War (which he seems to think was a rare old lark, sadly misreported ever since by "left-wing" academics and sit-com writers) shows that the religious-aristocractic view of the past, laced with ignorant flag-waving nationalism, is actively seeking to take control of history. Forget all those First World War poets who raged and railed against the hellish nightmare of the Western Front. No: a dimwitted politician now tells us that the war was a Good Thing, and anyone who questions that must be a "left-wing" radical.

In fact, the "Heroic age" has always rewritten history. It does so in order to cover its tracks and to pervert everyone's idea of the present. A government which is absolutely devoted to recreating the old aristocracy does not want you to think that the aristocratic officers of the First World War, or the aristocrats who sent so many millions to their deaths, were incompetent oafs. But the brainless attitude voiced by Michael Gove (Secretary of State for Education, would you believe?!) is symptomatic of a mindset that would happily send millions more to their deaths because they never learnt the lessons of history (how could they? Gove had already rewritten the book). And it's precisely that sort of thing that will undermine our civilisation.

Before we lose the internet, then - before we are banned from using it (because it's too democratic) or the infrastructure necessary to keep it going disintegrates (because it's "too expensive") - those of us who care about history really need to be making the most of our unprecedented opportunities to explore the past.

The "Heroic age" lied to us - repeatedly - about Arthur and his people. It was the "Heroic age" that invented the mythical "King Arthur" and changed the name of his wife from the authentic Gwenhwyfar to the familiar "Guinevere". And, let's face it, having lied to us before, it will lie to us again, given half a chance.

The only thing we can do is to uncover the historical truth, before the opportunity to do so is taken away from us. Arthur's last battle was fought at or near Alyth, in Scotland. A bit of determined research (internet and traditional) confirms this. But the "Heroic age" will have you believing that it happened somewhere else. Probably in the south. Evidence? Forget it. The "Heroic age" doesn't need evidence. It believes what it believes, and expects everyone else to believe it too. Evidence, be damned!

We could do our descendants a great big favour by using the internet intelligently, to challenge the foolish stories peddled by "Heroic age" propagandists. "King Arthur" never existed - he was an English invention - and the myth has always stood in the way of proper investigation. But tracing the historical Arthur is possible (and enjoyable), especially when we have all the resources of the internet at our command. Of course, the dogmatic voices of the "Heroic age" will shriek and shout and throw their little tantrums, but our great-grandchildren have the right to know what happened in the past. We have a duty to tell them, and not to let the past remain obliterated and re-engineered by fanatical demagogues, for whom everything must defend an extremist religious and/or political point-of-view.

So, in that sense, the story at the top of this post is a kind of metaphor. We are able - if we choose - to find out a great deal about Gwenhwyfar and her (possible) birthplace. But that won't last forever. Like the Iron Age hill-fort in which Arthur's wife was quite possibly born, there is a threat looming. The enemies of the truth are advancing.

There is still time to save the past from their bigoted opinions. But we do have to act.

Houses next door to Gwenhwyfar's birthplace? I'm not so worried about that, to be honest. Just so long as we succeed in uncovering and explaining who Gwenhwyfar was, while we still have the chance.

Tuesday, 17 December 2013

Finding Arthur

Very exciting to see this in the Scotsman newspaper yesterday. It's a short piece about Adam Ardrey's latest Arthurian publication, Finding Arthur: The Truth Behind the Legend of the Once and Future King.

I've had some contact with Adam Ardrey in recent years - although, keen as I am to preserve my historiographical independence, we've not exactly compared notes. I read his Finding Merlin when it came out in 2007, and we've communicated once or twice since then. But we're hardly collaborators.

I stress that for a couple of reasons. First, let me quote Ardrey's words from the back cover of Finding Merlin:

"If I am right, it would appear that, for 1,500 years, those with the power to do so have presented a history that, literally, suited their book, irrespective of its divergence from the evidence, and that the stories of Arthur and Merlin which form the British foundation myth are almost entirely pieces of propaganda based on various biases. If I am right, British history for the period from the late fifth to the early seventh century stands to be rewritten."

Sounds a bit like me, doesn't it? I too have argued that propaganda and bias have dictated the retelling of the Arthurian legends through the ages - just as propaganda and bias dictate what we allowed to hear, think and believe about William Shakespeare.

What is more, though, Adam Ardrey argues in his Finding Arthur book, not only that Artur mac Aedain was the original Arthur, but that he was buried on the Isle of Iona.

So we agree on that, too.

In other words, both of us have - independently - identified a known historical prince as the original "King Arthur", and we have both tracked down his grave to the sacred royal burial isle of the Scottish kings. That's two intelligent and inquisitive individuals who have each devoted years to the subject arriving at very similar conclusions.

I posted the piece in the Scotsman newspaper (link above) to Facebook yesterday, and it was quickly shared by a very successful historical novelist. The responses were most telling.

First came the observation that a Scottish historian had received coverage in a Scottish newspaper for his theory that Arthur was Scottish. Evidently, this was all very suspicious (I pointed out that I'm an English historian with Welsh roots, and so the suggestion that only a Scot would think Arthur might have been Scottish doesn't quite stand up). What makes this kneejerk rush to judgement so interesting is that there is no basis for it. It is, in fact, a form of projection. The fact that there is no evidence whatsoever that Arthur was what the English like to think he was gets instantly spun round, becoming no other culture is allowed to claim Arthur as its own, regardless of the evidence.

I posted a few days ago about the Ossian poems, translated from the Gaelic and published by James Macpherson in the 1760s, and the English response to the evidence of a thriving, heroic Gaelic culture at a time when England didn't even exist. The response was nothing short of blind fury - a kind of spluttering outrage that the "primitives" and "savages" of the Highlands and Islands should presume to imagine that they had any pedigree, any marvellous history, for such cultural treasures belonged only to the English!!!

The same prejudice shows itself whenever the Scottish Arthur is mentioned. Without viewing the evidence, the instinctive response is: "No, he can't have been." I repeat - without viewing the evidence. So we are not dealing with considered judgements here. We are dealing with prejudice, pure and simple. The implicit racism is apparent in the suggestion that only a Scottish historian would try to place Arthur in Scotland. Even though the very first Arthur to appear in any historical record was a Scot!

There is, then, a wall of prejudice encountered by anyone who, having spent years studying and researching the evidence, concludes that there was only one viable candidate for the prestigious role of the original Arthur - and it was Artur mac Aedain, whose father was ordained as the King of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574.

It is reassuring, then, to find that others who have devoted themselves to uncovering the historical truth behind the Arthur legend have arrived at much the same conclusion as me - he was Artur mac Aedain, and he was buried on Iona. The question, then, is when will the tide turn? When will the wall of prejudice crumble in the face of the evidence? When will the English finally admit that they have no claim at all to Arthur?

(I don't include the Welsh here because Arthur was British, and Welsh-speaking Britain extended at least as far north as the River Forth in his day; there are no grounds for presuming that, if Arthur was the son of a Scottish king, then he couldn't have been Welsh: rather, that argument is based on a misunderstanding of the geopolitics of 6th-century Britain.)

I'm tempted to post, over the next few days, a number of indisputable facts about Arthur. These are not assumptions, but genuine facts. And they all point in one direction, and one direction only.

The English might fight tooth and nail to cling to their myth of King Arthur. But there can be no reasonable doubt as to who the original Arthur was.

Unless you're determined to ignore the evidence, that is.

I've had some contact with Adam Ardrey in recent years - although, keen as I am to preserve my historiographical independence, we've not exactly compared notes. I read his Finding Merlin when it came out in 2007, and we've communicated once or twice since then. But we're hardly collaborators.

I stress that for a couple of reasons. First, let me quote Ardrey's words from the back cover of Finding Merlin:

"If I am right, it would appear that, for 1,500 years, those with the power to do so have presented a history that, literally, suited their book, irrespective of its divergence from the evidence, and that the stories of Arthur and Merlin which form the British foundation myth are almost entirely pieces of propaganda based on various biases. If I am right, British history for the period from the late fifth to the early seventh century stands to be rewritten."

Sounds a bit like me, doesn't it? I too have argued that propaganda and bias have dictated the retelling of the Arthurian legends through the ages - just as propaganda and bias dictate what we allowed to hear, think and believe about William Shakespeare.

What is more, though, Adam Ardrey argues in his Finding Arthur book, not only that Artur mac Aedain was the original Arthur, but that he was buried on the Isle of Iona.

So we agree on that, too.

In other words, both of us have - independently - identified a known historical prince as the original "King Arthur", and we have both tracked down his grave to the sacred royal burial isle of the Scottish kings. That's two intelligent and inquisitive individuals who have each devoted years to the subject arriving at very similar conclusions.

I posted the piece in the Scotsman newspaper (link above) to Facebook yesterday, and it was quickly shared by a very successful historical novelist. The responses were most telling.

First came the observation that a Scottish historian had received coverage in a Scottish newspaper for his theory that Arthur was Scottish. Evidently, this was all very suspicious (I pointed out that I'm an English historian with Welsh roots, and so the suggestion that only a Scot would think Arthur might have been Scottish doesn't quite stand up). What makes this kneejerk rush to judgement so interesting is that there is no basis for it. It is, in fact, a form of projection. The fact that there is no evidence whatsoever that Arthur was what the English like to think he was gets instantly spun round, becoming no other culture is allowed to claim Arthur as its own, regardless of the evidence.

I posted a few days ago about the Ossian poems, translated from the Gaelic and published by James Macpherson in the 1760s, and the English response to the evidence of a thriving, heroic Gaelic culture at a time when England didn't even exist. The response was nothing short of blind fury - a kind of spluttering outrage that the "primitives" and "savages" of the Highlands and Islands should presume to imagine that they had any pedigree, any marvellous history, for such cultural treasures belonged only to the English!!!

The same prejudice shows itself whenever the Scottish Arthur is mentioned. Without viewing the evidence, the instinctive response is: "No, he can't have been." I repeat - without viewing the evidence. So we are not dealing with considered judgements here. We are dealing with prejudice, pure and simple. The implicit racism is apparent in the suggestion that only a Scottish historian would try to place Arthur in Scotland. Even though the very first Arthur to appear in any historical record was a Scot!

There is, then, a wall of prejudice encountered by anyone who, having spent years studying and researching the evidence, concludes that there was only one viable candidate for the prestigious role of the original Arthur - and it was Artur mac Aedain, whose father was ordained as the King of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574.

It is reassuring, then, to find that others who have devoted themselves to uncovering the historical truth behind the Arthur legend have arrived at much the same conclusion as me - he was Artur mac Aedain, and he was buried on Iona. The question, then, is when will the tide turn? When will the wall of prejudice crumble in the face of the evidence? When will the English finally admit that they have no claim at all to Arthur?

(I don't include the Welsh here because Arthur was British, and Welsh-speaking Britain extended at least as far north as the River Forth in his day; there are no grounds for presuming that, if Arthur was the son of a Scottish king, then he couldn't have been Welsh: rather, that argument is based on a misunderstanding of the geopolitics of 6th-century Britain.)

I'm tempted to post, over the next few days, a number of indisputable facts about Arthur. These are not assumptions, but genuine facts. And they all point in one direction, and one direction only.

The English might fight tooth and nail to cling to their myth of King Arthur. But there can be no reasonable doubt as to who the original Arthur was.

Unless you're determined to ignore the evidence, that is.

Labels:

Arthur,

Arthur's Grave,

Iona,

Merlin,

Ossian,

Scotland,

Shakespeare,

St Columba

Saturday, 14 December 2013

Ossian: Culture and Prejudice

It's taken me a while, but I've finally got round to researching the poems of Ossian.

"So what?" I hear you cry. Well, each to his own.

Let me fill you in.

James Macpherson was born in the Scottish Highlands in 1736. A native Gaelic speaker, he wasn't quite ten years old when the Jacobite rebellion under Bonnie Prince Charlie came to a terrible end at Culloden, not so very far from where Macpherson had grown up.

There had been prominent rebels in his family - including Cluny Macpherson, who makes a colourful appearance in Robert Louis Stevenson's Kidnapped.

James Macpherson was clever, quick-witted and well-educated. In 1760, he published Fragments of Ancient Poetry - Collected in the Highlands of Scotland and Translated from the Gaelic or Erse Language. These Fragments introduced the world to the ancient world of Fingal (Fionn mac Cumhail), his son Ossian and grandson Oscar (yes, Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was named after him). They were an instant success.

The Scottish literati then raised the funds for Macpherson to make a research trip to the Highlands and Islands with a view to collecting more scraps of traditional Gaelic verse, either orally or in manuscript form. The result of this expedition was Fingal: An Ancient Epic Poem in Sixth Books.

Macpherson had made his name. His Ossianic collections were the talk of Europe and beyond. Thomas Jefferson considered them his favourite books; Napoleon Buonaparte never went into battle without a copy to hand, and Goethe was hugely inspired by the Gaelic epic. Romanticism - the predominant aesthetic movement of the 19th century - owed a great deal to Macpherson's work. Felix Mendelssohn made a sort of pilgrimage to the Western Isles after reading the Ossian poems, and was inspired to write his stirring Hebridean Overture, although sea-sickness had prevented him from viewing "Fingal's Cave" on Staffa.

But the English hated the Ossian poems. Led by the bullish figure of Dr Samuel Johnson, the southern establishment poured scorn on Macpherson's efforts. Johnson demanded that Macpherson reveal his sources and produce the Gaelic manuscripts from which he had drawn his translations. As far as Dr Johnson was concerned, the whole thing was a hoax. There were no historic manuscripts concerning Fingal. Macpherson had made the whole thing up.

Not true. There were mentions of Fingal and Ossian in historical manuscripts, and subsequent research has shown that Macpherson did indeed base his work on original, authentic Gaelic poetry. And yet Macpherson - and Ossian - are little known today. So one could say that Dr Johnson and his English crew succeeded. They threw enough mud for some of it to stick.

Why, though? Why was it so important to Dr Johnson, and others like him, to undermine James Macpherson's achievements?

At the time, Gaelic society was in decline. It has since been sentimentalised and fetishised, but first its roots had to be torn up and the culture pretty much destroyed.

The crowns of England and Scotland had been united in 1603 under James Stuart, the sixth King James of Scotland (but usually referred to as James I - his English designation). It was not until 1707, though, that the Scots were bribed and bullied into accepting an Act of Union with England. This was very much to England's benefit - it meant that France lost a valuable ally north of England's border - and very much to Scotland's disadvantage. Indeed, the Union was detested on both sides of the English-Scottish border.

The last serious attempt to break up the Union, or to restore the Stuart line to the throne (if only in Scotland), came when Charles Edward Stuart landed with seven men in the Outer Hebrides. It ended with the disaster at Culloden in 1746. The English, under the "Butcher" Duke of Cumberland, a son of the reigning Hanoverian king, raped and massacred their way through the Highlands. The wearing of Scottish dress (the tartan kilt) was banned, as was the possession of weapons.

Before too long, the time-honoured clan system was breaking down. The clan chiefs were replaced by landlords, who held no sense of responsibility to the inhabitants of the Highlands. Sheep were more profitable than people, and so houses were burned down, possessions confiscated, and thousands of men, women and children herded into overcrowded vessels to make long and painful journeys to the farthest flung corners of the Empire. The Highlands became a wasteland, an exclusive playground for the very rich.

With the determined annihilation of Gaelic culture well and truly underway, Macpherson's publications were a bit of a problem. They demonstrated that the culture of the Highlands (and, in particular, the west) was truly ancient. Some even considered the Ossianic poems comparable with the works of Homer and Virgil. It was as if, just as the English and their supporters in the Lowlands were systematically crushing Highland society, a Highlander had come along and shown that the Gaels had a culture and tradition which far surpassed anything that any Englishman could boast of.

To men like Dr Samuel Johnson, the Scots were primitives, a ragged bunch of scheming savages. English racism - never very far from the surface - was making exaggerated and hysterical claims about Scots migrating en masse to London and taking jobs, houses and women (sound familiar?). South of the border, words like "Scot" and "Scottish" were a form of abuse

Things worsened when John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, became the first Scottish prime minister of Great Britain. Bute was a favourite of King George III (the "mad" one), but he bore the hated name of Stuart, and he was a Scot - so the English loathed him. Macpherson had dedicated his Ossianic works to Lord Bute, which gave Englishmen like Dr Johnson another reason to attack Macpherson and his discoveries.

There is much that is magnificent in the Ossianic poems, even if Macpherson had embellished the original Gaelic verses he collected throughout the Highlands and Islands. They give flashes of insight into a heroic society and glimpses of life at a time when Christianity was just beginning to establish itself (there are no Christian references in the poems). What is more, they offer proof that the western seaboard of Scotland was home to a remarkable culture before the invading Angles and Saxons converged to form England. They deserve to be better known. No; more than that - they are part of the ancestral heritage of the British Isles, and it was a cultural atrocity on the part of the English to try to wipe them from the record and to impugn the reputation of the man who collected, translated and published them.

And there's more. The Ossian poems give us an insight into the society of Arthur. Yes, Arthur. That Arthur - the one the English falsely insist on calling "King Arthur".

English prejudices run deep. If they can't have Arthur all to themselves, then no one can.

The real, original, historical Arthur was a Scottish prince. There never was an "English" King Arthur, and no evidence at all exists for an Arthur in the south. He was a North Briton, and his world was the world of Fingal and Ossian and Oscar.

But just as English scholars refused to allow the Scots to have an ancient, heroic culture - refused even to let them have a language, or a home - so English commentators continue to tell lies about Arthur, if only to prevent the world from knowing that his father was King of the Scots.

One day - let us hope - the Ossianic poems will take their place alongside the native tales of Arthur and his heroes (which continually refer to "the North"). Macpherson will be honoured as he should be: as the man who preserved these traces of authentic tradition and was cruelly satirised and savagely lambasted for doing so. The crimes committed against the culture and people of the Highlands will be fully recognised and acknowledged. And it will be possible to investigate and celebrate the genuine Arthur of history, rather than the insipid legendary concoction foisted upon us by the propagandists of the south.

"So what?" I hear you cry. Well, each to his own.

Let me fill you in.

James Macpherson was born in the Scottish Highlands in 1736. A native Gaelic speaker, he wasn't quite ten years old when the Jacobite rebellion under Bonnie Prince Charlie came to a terrible end at Culloden, not so very far from where Macpherson had grown up.

There had been prominent rebels in his family - including Cluny Macpherson, who makes a colourful appearance in Robert Louis Stevenson's Kidnapped.

James Macpherson was clever, quick-witted and well-educated. In 1760, he published Fragments of Ancient Poetry - Collected in the Highlands of Scotland and Translated from the Gaelic or Erse Language. These Fragments introduced the world to the ancient world of Fingal (Fionn mac Cumhail), his son Ossian and grandson Oscar (yes, Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was named after him). They were an instant success.

The Scottish literati then raised the funds for Macpherson to make a research trip to the Highlands and Islands with a view to collecting more scraps of traditional Gaelic verse, either orally or in manuscript form. The result of this expedition was Fingal: An Ancient Epic Poem in Sixth Books.

Macpherson had made his name. His Ossianic collections were the talk of Europe and beyond. Thomas Jefferson considered them his favourite books; Napoleon Buonaparte never went into battle without a copy to hand, and Goethe was hugely inspired by the Gaelic epic. Romanticism - the predominant aesthetic movement of the 19th century - owed a great deal to Macpherson's work. Felix Mendelssohn made a sort of pilgrimage to the Western Isles after reading the Ossian poems, and was inspired to write his stirring Hebridean Overture, although sea-sickness had prevented him from viewing "Fingal's Cave" on Staffa.

But the English hated the Ossian poems. Led by the bullish figure of Dr Samuel Johnson, the southern establishment poured scorn on Macpherson's efforts. Johnson demanded that Macpherson reveal his sources and produce the Gaelic manuscripts from which he had drawn his translations. As far as Dr Johnson was concerned, the whole thing was a hoax. There were no historic manuscripts concerning Fingal. Macpherson had made the whole thing up.

Not true. There were mentions of Fingal and Ossian in historical manuscripts, and subsequent research has shown that Macpherson did indeed base his work on original, authentic Gaelic poetry. And yet Macpherson - and Ossian - are little known today. So one could say that Dr Johnson and his English crew succeeded. They threw enough mud for some of it to stick.

Why, though? Why was it so important to Dr Johnson, and others like him, to undermine James Macpherson's achievements?

At the time, Gaelic society was in decline. It has since been sentimentalised and fetishised, but first its roots had to be torn up and the culture pretty much destroyed.

The crowns of England and Scotland had been united in 1603 under James Stuart, the sixth King James of Scotland (but usually referred to as James I - his English designation). It was not until 1707, though, that the Scots were bribed and bullied into accepting an Act of Union with England. This was very much to England's benefit - it meant that France lost a valuable ally north of England's border - and very much to Scotland's disadvantage. Indeed, the Union was detested on both sides of the English-Scottish border.

The last serious attempt to break up the Union, or to restore the Stuart line to the throne (if only in Scotland), came when Charles Edward Stuart landed with seven men in the Outer Hebrides. It ended with the disaster at Culloden in 1746. The English, under the "Butcher" Duke of Cumberland, a son of the reigning Hanoverian king, raped and massacred their way through the Highlands. The wearing of Scottish dress (the tartan kilt) was banned, as was the possession of weapons.

Before too long, the time-honoured clan system was breaking down. The clan chiefs were replaced by landlords, who held no sense of responsibility to the inhabitants of the Highlands. Sheep were more profitable than people, and so houses were burned down, possessions confiscated, and thousands of men, women and children herded into overcrowded vessels to make long and painful journeys to the farthest flung corners of the Empire. The Highlands became a wasteland, an exclusive playground for the very rich.

With the determined annihilation of Gaelic culture well and truly underway, Macpherson's publications were a bit of a problem. They demonstrated that the culture of the Highlands (and, in particular, the west) was truly ancient. Some even considered the Ossianic poems comparable with the works of Homer and Virgil. It was as if, just as the English and their supporters in the Lowlands were systematically crushing Highland society, a Highlander had come along and shown that the Gaels had a culture and tradition which far surpassed anything that any Englishman could boast of.

To men like Dr Samuel Johnson, the Scots were primitives, a ragged bunch of scheming savages. English racism - never very far from the surface - was making exaggerated and hysterical claims about Scots migrating en masse to London and taking jobs, houses and women (sound familiar?). South of the border, words like "Scot" and "Scottish" were a form of abuse