A sneak preview, friends, of The Grail, coming soon from Moon Books.

Publication in March 2015.

Looking good, isn't it?

I've set up a Facebook page for the new book (click on "Facebook page" to go straight to it) and I'll keep you updated as the launch date draws nearer.

Meantime, work proceeds on Shakespeare's Son - my "Life of Sir William Davenant" - which has been keeping me pretty busy. And hoping to have some interesting news pretty soon regarding Shakespeare's skull.

Plenty more to come, folks!

The Future of History

Monday, 1 December 2014

Sunday, 2 November 2014

Pagan Pages

Just been told that an interview with me is now up on the PaganPages.org website.

So, with thanks to Mabh Savage, I give you ... The Pagan Pages Interview with Author Simon Stirling. I think it's a good one.

Toodle-pip!

So, with thanks to Mabh Savage, I give you ... The Pagan Pages Interview with Author Simon Stirling. I think it's a good one.

Toodle-pip!

Labels:

Arthur,

Artuir mac Aedain,

Beltane,

Grail,

Gunpowder Plot,

Halloween,

King Arthur Conspiracy,

Moon Books,

Muirgein,

Myrddin Wyllt,

Scotland,

The History Press,

Who Killed William Shakespeare

Monday, 27 October 2014

The Faces of Shakespeare

Morning, all!

I'll be on BBC Coventry and Warwickshire local radio this morning, talking about the story of Shakespeare's skull. There have been developments in that arena, but I can't go public with them just yet.

HOWEVER ... Goldsmiths, University of London, have just published their GLITS e-journal for the past year, and my illustrated paper on The Faces of Shakespeare - Revealing Shakespeare's Life and Death through Portraits and Other Objects is the second item on the menu.

Here's the link to my paper in the Goldsmiths GLITS journal.

More to come later.

I'll be on BBC Coventry and Warwickshire local radio this morning, talking about the story of Shakespeare's skull. There have been developments in that arena, but I can't go public with them just yet.

HOWEVER ... Goldsmiths, University of London, have just published their GLITS e-journal for the past year, and my illustrated paper on The Faces of Shakespeare - Revealing Shakespeare's Life and Death through Portraits and Other Objects is the second item on the menu.

Here's the link to my paper in the Goldsmiths GLITS journal.

More to come later.

Thursday, 2 October 2014

The Matter of Scotland

The Scottish Statesman, a new online newspaper for Scotland, launched today.

Here's my first contribution. It's about Arthur in Scotland, and the English approach to history.

More news to come ...

Here's my first contribution. It's about Arthur in Scotland, and the English approach to history.

More news to come ...

Monday, 15 September 2014

That Eureka Moment

Here's me - in some very distinguished company - helping to celebrate The History Vault's first year of fantastic activity.

Really glad to have been part of it.

Here's the link - please click and read.

Really glad to have been part of it.

Here's the link - please click and read.

Friday, 29 August 2014

Gunpowder Treason - a 400 Year Old Lie

96 people died at the Hillsborough Stadium on 15 April 1989. Even as the full scale of the disaster was becoming apparent, the authorities - police, politicians, the press - were concocting a story about it. It was all caused by drunken football fans, they said. Those same fans had picked the pockets of the dead and urinated on the paramedics who were trying to help.

We now know that that story was a pack of lies, although it took more than two decades for the truth to come out. But what had happened was a political elite, composed of extremists, had cooked up and spun a false yarn designed to demonise a perceived enemy. That enemy was, (a) football fans, who were seen as hooligans, and (b) the people of Liverpool, who remained obstinately opposed to the socio-economic insanity of Thatcherism. The disaster provided an excuse for the State to denigrate those who seemed unable to fight back while, at the same time, covering up its own incompetence.

So what has that got to do with the Gunpowder Plot?

Well, we now know the truth about Hillsborough, 25 years ago, and few commentators would have the gall to repeat the lies told by the police and the government back then. We do not, however, know the truth about the "powder treason", 409 years ago, because historians insist on repeating the lies.

The Radio Times reports that BBC2 has "just given the green light to Gunpowder 5/11: the Greatest Terror Plot". "It's a total retelling," says the writer, "which uses the interrogation of Fawkes's number three, Thomas Winter, who gave away the whole story."

Okay, before we go any further ...

Fawkes was not the ringleader. That was Robert Catesby. Guy Fawkes was essentially a hired hand. Arguably, Thomas Wintour was Catesby's number three. But did he give away the whole story?

"We restage the interrogation and get inside the plot, which was huge", continues the writer, Adam Kemp, breathlessly. Restage the interrogation, hunh? That'll be interesting. I can only assume we will mention the fact that Thomas Wintour had been shot in the shoulder when he and his comrades were finally cornered by a local posse. Whether he would have been capable of composing his ten-page confession in neat handwriting is open to doubt. But the signature on the confession - a rather bold "Thomas Winter" - wasn't his own. He spelled his name "Wintour".

Note that Adam Kemp referred to "Thomas Winter". He's using the name used by the Jacobean government, not the individual whose name it actually was. Which means that his "total retelling" will, in all probability, be exactly the same version of events as that which was cooked up at the time by government ministers. It won't be a "total retelling" at all. Just another re-tread.

He goes on: "They would have got everyone under one roof, the royal family and the entire governing elite and bishops. There is truly nothing that can come close. It really was big,"

Yes, it was. It would have been enormous. If it had happened. And yet, truth be told, there never was even the slightest risk that the king and his lords would be blown to smithereens. Not a chance in hell.

Let's start with the gunpowder. It was sourced from the Tower of London, where the government (which had the monopoly on gunpowder) kept its supply under the supervision of Sir George Carew. Carew, a government insider, had just become Baron Carew of Clopton. He somehow managed to let Clopton House, his estate just outside Stratford-upon-Avon, to the gunpowder plotters. Nobody seems to have thought that was odd. But the government resolutely blocked an investigation into how the gunpowder had been removed from the Tower.

How much gunpowder was there? Good question. A credible source said one barrel. Guy Fawkes confessed to secreting twenty barrels in the Parliament building. Sir Robert Cecil, who knew more about the plot than anybody, wrote of there having been 34 barrels. The figure eventually settled on was 36 barrels.

So nobody was quite sure how much gunpowder had been involved, and no explanation was ever given for its mysterious disappearance from the government's store. A large quantity of gunpowder was returned to the Tower a couple of days after Fawkes's arrest and was registered as "decayed". Its constituent elements had separated. It would never have blown up anything, let alone the royal family and entire governing elite. There wouldn't even have been a puff!

Reliable witnesses saw the real ringleaders - Robert Catesby and Thomas Percy - emerging from Sir Robert Cecil's house in the early hours of the morning, just days before the plot was discovered. That's like the perpetrators of the 7/7 London bombings being spotted sneaking out of 10 Downing Street a few days before they detonated their rucksacks on crowded tubes and buses (except, of course, that the gunpowder plotters explosives were "decayed" and weren't going to blow up). Thomas Percy himself was a government insider, in the king's service at the time. His job was to make sure that the plot proceeded and to implicate his kinsman, the Earl of Northumberland, whom Sir Robert Cecil has sworn to destroy.

Catesby, on the other hand, spent much of the year leading up to the plot's discovery trying to trick Father Henry Garnet into condoning the plot. The government repeatedly delayed the opening of Parliament so that Catesby would have more time to incriminate Garnet. Catesby was aided in his attempts to entrap Garnet by William Parker, Lord Monteagle. Monteagle was eventually credited with exposing the plot and rewarded handsomely - every mention of him in the plotters' confessions was redacted. Both Catesby and Percy, who had engineered the plot, were killed, rather than taken alive, on the instructions of Sir Robert Cecil.

The simple fact is that the Gunpowder Plot never really was. True, some of its members were ardent Catholics who joined what they believed would be a blow for freedom. But the main players were government stooges (William Shakespeare - who was alarmingly close to the events - made this clear in his plays, Macbeth and Coriolanus). In other words, the Gunpowder Plot was pretty much the same as every other plot of its time. These supposed "plots" were "discovered" on a more-or-less annual basis, and they all followed the same pattern - a good example being the Babington Plot of 1586. A Catholic patsy was lured into a fake conspiracy by government agents, who then "discovered" the plot which they themselves had manufactured. There was massive publicity, and the Protestant extremists at the heart of the government got to enact the policies which they'd been hankering to put into place: the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots - a Catholic contender for the English throne - or the execution of Father Henry Garnet, Superior of the Jesuits in England.

The constant repetition of the government's lies about the Gunpowder Plot is an offense to history. It amounts to a 400-year propaganda campaign, and it speaks volumes that British historians would rather regurgitate the falsehoods about Catholic militancy than investigate the truth about Protestant duplicity.

The Gunpowder Plot is more than just an iconic incident-that-didn't-happen. It led to the English Civil War; John Pym and John Milton were obsessed with it. Like so many others in those paranoid times, they had swallowed the lies spouted by the likes of Sir Robert Cecil (for his own personal gain). So successful were the propagandists in broadcasting the cooked-up story of the Gunpowder Plot, it fuelled the anti-Catholic rhetoric of the fanatics for decades. Arguably, it continues to fuel our irrational fears of some nefarious, fanatical "enemy within" which is "out to get us" because it "hates our freedom". That sort of nonsense has been doing the rounds since the Gunpowder Plot, and it's precisely why the plot was invented. Fear is a useful tool of government.

Historians repeat the Gunpowder Plot lie for a simple reason. Englishness has always been difficult to define. It's easier to explain what being "English" means in terms of what it is not - Catholic, Jewish, Irish, Scottish, French, etc. - than in terms of what it is. That is why the English lay claim to a "tolerance" and a sense of "fair play" which they so seldom exhibit. If they were honest with themselves, they'd have to say that the simplest way to be "English" is to hate, fear and abuse anyone who isn't. But that problem created its own national myth, embroidered by generations of Whig historians anxious to justify every atrocity and outrage of our past as a necessary part of our Manifest Destiny. The State had to persecute Catholics because the Catholics wanted to blow up the State (even though they never did; never actually came close). To be English is to be Protestant. The Catholics were, ipso facto, the enemy - like those football supporters who died at Hillsborough. They were "not on our side", so they could be slandered.

It really is time to put the lie of the Gunpowder Plot to bed. And I doubt very much indeed that the BBC's Gunpowder 5/11: the Greatest Terror Plot will even try to do that. No. Just going by the title alone, it seems most likely that it'll be yet another repetition of the old, old lie, designed to excuse the most vicious persecution of English citizens who happened to be Catholic.

Such a slavish acceptance and repetition of past propaganda isn't history, though. It's telling fairy tales for political purposes.

We now know that that story was a pack of lies, although it took more than two decades for the truth to come out. But what had happened was a political elite, composed of extremists, had cooked up and spun a false yarn designed to demonise a perceived enemy. That enemy was, (a) football fans, who were seen as hooligans, and (b) the people of Liverpool, who remained obstinately opposed to the socio-economic insanity of Thatcherism. The disaster provided an excuse for the State to denigrate those who seemed unable to fight back while, at the same time, covering up its own incompetence.

So what has that got to do with the Gunpowder Plot?

Well, we now know the truth about Hillsborough, 25 years ago, and few commentators would have the gall to repeat the lies told by the police and the government back then. We do not, however, know the truth about the "powder treason", 409 years ago, because historians insist on repeating the lies.

The Radio Times reports that BBC2 has "just given the green light to Gunpowder 5/11: the Greatest Terror Plot". "It's a total retelling," says the writer, "which uses the interrogation of Fawkes's number three, Thomas Winter, who gave away the whole story."

Okay, before we go any further ...

Fawkes was not the ringleader. That was Robert Catesby. Guy Fawkes was essentially a hired hand. Arguably, Thomas Wintour was Catesby's number three. But did he give away the whole story?

"We restage the interrogation and get inside the plot, which was huge", continues the writer, Adam Kemp, breathlessly. Restage the interrogation, hunh? That'll be interesting. I can only assume we will mention the fact that Thomas Wintour had been shot in the shoulder when he and his comrades were finally cornered by a local posse. Whether he would have been capable of composing his ten-page confession in neat handwriting is open to doubt. But the signature on the confession - a rather bold "Thomas Winter" - wasn't his own. He spelled his name "Wintour".

Note that Adam Kemp referred to "Thomas Winter". He's using the name used by the Jacobean government, not the individual whose name it actually was. Which means that his "total retelling" will, in all probability, be exactly the same version of events as that which was cooked up at the time by government ministers. It won't be a "total retelling" at all. Just another re-tread.

He goes on: "They would have got everyone under one roof, the royal family and the entire governing elite and bishops. There is truly nothing that can come close. It really was big,"

Yes, it was. It would have been enormous. If it had happened. And yet, truth be told, there never was even the slightest risk that the king and his lords would be blown to smithereens. Not a chance in hell.

Let's start with the gunpowder. It was sourced from the Tower of London, where the government (which had the monopoly on gunpowder) kept its supply under the supervision of Sir George Carew. Carew, a government insider, had just become Baron Carew of Clopton. He somehow managed to let Clopton House, his estate just outside Stratford-upon-Avon, to the gunpowder plotters. Nobody seems to have thought that was odd. But the government resolutely blocked an investigation into how the gunpowder had been removed from the Tower.

How much gunpowder was there? Good question. A credible source said one barrel. Guy Fawkes confessed to secreting twenty barrels in the Parliament building. Sir Robert Cecil, who knew more about the plot than anybody, wrote of there having been 34 barrels. The figure eventually settled on was 36 barrels.

So nobody was quite sure how much gunpowder had been involved, and no explanation was ever given for its mysterious disappearance from the government's store. A large quantity of gunpowder was returned to the Tower a couple of days after Fawkes's arrest and was registered as "decayed". Its constituent elements had separated. It would never have blown up anything, let alone the royal family and entire governing elite. There wouldn't even have been a puff!

Reliable witnesses saw the real ringleaders - Robert Catesby and Thomas Percy - emerging from Sir Robert Cecil's house in the early hours of the morning, just days before the plot was discovered. That's like the perpetrators of the 7/7 London bombings being spotted sneaking out of 10 Downing Street a few days before they detonated their rucksacks on crowded tubes and buses (except, of course, that the gunpowder plotters explosives were "decayed" and weren't going to blow up). Thomas Percy himself was a government insider, in the king's service at the time. His job was to make sure that the plot proceeded and to implicate his kinsman, the Earl of Northumberland, whom Sir Robert Cecil has sworn to destroy.

Catesby, on the other hand, spent much of the year leading up to the plot's discovery trying to trick Father Henry Garnet into condoning the plot. The government repeatedly delayed the opening of Parliament so that Catesby would have more time to incriminate Garnet. Catesby was aided in his attempts to entrap Garnet by William Parker, Lord Monteagle. Monteagle was eventually credited with exposing the plot and rewarded handsomely - every mention of him in the plotters' confessions was redacted. Both Catesby and Percy, who had engineered the plot, were killed, rather than taken alive, on the instructions of Sir Robert Cecil.

The simple fact is that the Gunpowder Plot never really was. True, some of its members were ardent Catholics who joined what they believed would be a blow for freedom. But the main players were government stooges (William Shakespeare - who was alarmingly close to the events - made this clear in his plays, Macbeth and Coriolanus). In other words, the Gunpowder Plot was pretty much the same as every other plot of its time. These supposed "plots" were "discovered" on a more-or-less annual basis, and they all followed the same pattern - a good example being the Babington Plot of 1586. A Catholic patsy was lured into a fake conspiracy by government agents, who then "discovered" the plot which they themselves had manufactured. There was massive publicity, and the Protestant extremists at the heart of the government got to enact the policies which they'd been hankering to put into place: the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots - a Catholic contender for the English throne - or the execution of Father Henry Garnet, Superior of the Jesuits in England.

The constant repetition of the government's lies about the Gunpowder Plot is an offense to history. It amounts to a 400-year propaganda campaign, and it speaks volumes that British historians would rather regurgitate the falsehoods about Catholic militancy than investigate the truth about Protestant duplicity.

The Gunpowder Plot is more than just an iconic incident-that-didn't-happen. It led to the English Civil War; John Pym and John Milton were obsessed with it. Like so many others in those paranoid times, they had swallowed the lies spouted by the likes of Sir Robert Cecil (for his own personal gain). So successful were the propagandists in broadcasting the cooked-up story of the Gunpowder Plot, it fuelled the anti-Catholic rhetoric of the fanatics for decades. Arguably, it continues to fuel our irrational fears of some nefarious, fanatical "enemy within" which is "out to get us" because it "hates our freedom". That sort of nonsense has been doing the rounds since the Gunpowder Plot, and it's precisely why the plot was invented. Fear is a useful tool of government.

Historians repeat the Gunpowder Plot lie for a simple reason. Englishness has always been difficult to define. It's easier to explain what being "English" means in terms of what it is not - Catholic, Jewish, Irish, Scottish, French, etc. - than in terms of what it is. That is why the English lay claim to a "tolerance" and a sense of "fair play" which they so seldom exhibit. If they were honest with themselves, they'd have to say that the simplest way to be "English" is to hate, fear and abuse anyone who isn't. But that problem created its own national myth, embroidered by generations of Whig historians anxious to justify every atrocity and outrage of our past as a necessary part of our Manifest Destiny. The State had to persecute Catholics because the Catholics wanted to blow up the State (even though they never did; never actually came close). To be English is to be Protestant. The Catholics were, ipso facto, the enemy - like those football supporters who died at Hillsborough. They were "not on our side", so they could be slandered.

It really is time to put the lie of the Gunpowder Plot to bed. And I doubt very much indeed that the BBC's Gunpowder 5/11: the Greatest Terror Plot will even try to do that. No. Just going by the title alone, it seems most likely that it'll be yet another repetition of the old, old lie, designed to excuse the most vicious persecution of English citizens who happened to be Catholic.

Such a slavish acceptance and repetition of past propaganda isn't history, though. It's telling fairy tales for political purposes.

Wednesday, 27 August 2014

The X Factor

I treated myself, the other day. I bought a copy of Allan Campbell McLean's The Hill of the Red Fox.

It must be 35 years since I borrowed that book from my local library in Birmingham. Time spent on holiday in Scotland had planted a deep-rooted fascination, bordering on thirst, for all things Scottish. The Hill of the Red Fox, which sits comfortably alongside Stevenson's Kidnapped and Buchan's Thirty-Nine Steps, was one of the stories which allowed me to keep in touch, as it were, with western Scotland when I was back home in the West Midlands. It also inspired my interest in the Gaelic language (there is a little glossary of Gaelic terms in the back, and this fascinated me as a kid - the Gaelic has a dignity, a romance, and a connection with nature that English seldom matches). When the chance arose, I opted to take Gaelic Studies at the University of Glasgow, largely because of the glossaries I had previously found in such books as The Hill of the Red Fox.

Rooting around a charity bookshop in Evesham, a day or two after I'd read The Hill of the Red Fox, I came across an old copy of another novel by Allan Campbell McLean. The Year of the Stranger. I'm reading it now.

Like The Hill of the Red Fox, it's set on the Isle of Skye. But whereas the former novel takes place during the Cold War 1950s and involves espionage, murder and nuclear secrets (all grist to my adolescent mill, back in the late 70s), The Year of the Stranger takes place in the Victorian era. And it paints a perfectly clear picture of the gross injustices of aristocratic rule in the Highlands and Islands.

There's a referendum coming up. The people of Scotland have a choice - do they want independence, or are they anxious to remain in the United Kingdom? I don't have a vote, although I wish I did. The vote will take place the day before my 12th wedding anniversary. I married a woman who is half-Scots. We were married on the Isle of Iona. I can think of no more exciting anniversary present than a resounding YES to Scottish independence.

There are many, many reasons why it's a good idea. Some of them are to be found in The Year of the Stranger. It's a reminder that, after the Treaty of Union between England and Scotland in 1707, the people of Scotland pretty much lost every last one of their rights. They were cleared from their native lands, forced out of their homes to make way for sheep (a lucrative business, but one that destroyed the ecology of the Highlands) or simply to provide an absentee landlord and his wealthy friends with even more empty land to call their own. Servile deference was demanded by the anglicised gentry. That deference was not just demanded - it was imposed by force. While the aristocracy turned Scotland into their own exclusive playground, those to whom the land had belonged were shipped off to America, Canada, Australia, in their thousands. Those who remained behind had no choice but to tug their forelocks and grovel to the latest outsider who called himself their landlord. A terrible punishment awaited those who resisted. The fish in the rivers belonged to the aristocracy; the deer on the hills were theirs. They owned - or believed that they owned - everything.

The spirit of the Highlanders was all but broken. Many went off to fight in Britain's wars (sustaining a disproportionate amount of casualties, compared with the rest of the UK). Those at home found themselves oppressed, not just by the aristocrats, who could buy the law, but also by religious extremists, who forced their neighbours into ever more demoralised forms of mental straitjacket. As always, aristocracy and religious zealotry went hand in hand. The once-proud people learned to live in fear of their outlandish landlords and their crazy preachers. They had become little more than slaves.

It took the 20th century to pull Scotland - and the rest of the UK - out of that moral, political and economic insanity. Votes for all, regardless of income and gender; universal education; welfare; healthcare; collective bargaining. Gradually, civilisation dawned. But all that has now been undermined.

Tom Devine, probably the most respected historian in Scotland, explained why it was time to vote YES to independence. The union was of benefit (he feels) from the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 up till the Thatcherite revolution of 1979. But that's when union with England ceased to be of any real advantage to the Scots. The neoliberal agenda being so ruthlessly pursued by successive British governments is nothing more than a determined attempt to turn back the clock. While the stark picture of gross economic, political and legal inequality as presented by Allan Campbell McLean in The Year of the Stranger strikes us today as quaintly barbaric, be in no doubt that to those who currently hold power in Westminster, that sort of rampant injustice makes perfect sense.

Social and economic progress was turned around in 1979. Margaret Thatcher's simplistic economic policies were an absolute disaster - and yet the receipts from (Scottish) North Sea Oil and Gas propped up the nation's finances, so that things didn't look quite as bad as they really were (and there was always the press to mislead us as to what was really going on). But if the natural wealth of Scotland bailed out Thatcher's failed experiments, it was the Scots who paid the greatest price - their industry practically destroyed. Nuclear weapons? The English wouldn't want them anywhere near their coastal towns. Put them within 25 miles of the most densely populated area in Scotland. Oh, and the poll tax that nobody wanted? That was visited on the Scots a full year before they tried it out in England. Scotland's wealth subsidised Westminster, but rather than show the slightest gratitude, Tory commentators chose to brand the Scots "scroungers" and "subsidy-junkies". That is what colonisation looks like.

If Scotland chooses not to free itself of the shackles of aggressive, patronising, condescending, grasping Westminster rule, it will live to regret it. Scotland is one of the richest countries in the world, and yet hundreds of thousands of its children are falling into poverty as a result of Tory ideology (there is only one - ONE - Tory MP in Scotland). A person from Aberdeenshire, when asked to explain why she is voting YES, said, "When I look out to sea, I see nothing but oil-rigs. When I look inland, I see nothing but food-banks."

And that, folks, is your warning. History is repeating itself. A corrupt and self-serving aristocracy is seeking to take us back to those dark days in which we all had to doff our caps to the idiots who lorded it over us; that, or we starved. They could take our homes, throw us out into the cold, send us overseas, deny us our rights and use lethal force against us. Their obscene wealth was stolen from the millions who actually earned it.

England can, if it chooses, wrap itself up in the Downton Abbey lies about the past and carry on down the road towards government by half-baked toffs and their vicious minions, or the only apparent alternative, which is arse-about-face UKIP-style fascism. But if the Scots want to avoid the iniquities of history being revisited upon them, they need to take the chance that is now on offer.

For one thing is clear. Those who cling to the idea of the union do so for one of two reasons.

The first is that they are the very aristocrats who believe that they own Scotland (and its people, and its natural resources) and who insist on maintaining their privileges, no matter what it takes.

The other is that they have some vague hope that somehow, the Scots and the English and the Welsh and the people of Northern Ireland will someday turn the neoliberal juggernaut around and get us back on the road to democracy and decency. But that ain't gonna happen. The English are too busy blaming everybody else in the world for their mistakes to wake up to the very real trouble they're in. The Scots are already awake. The YES campaign is by far the biggest, broadest, most inclusive and engaged grassroots campaign I've ever seen: a genuine movement of the people. It's not about nationalism. It's about reality. They know that the union is finished, and that Thatcherism killed it. They see democracy slipping ever further and further away, as the gentry comes marching back to lay claim to what it never earned. The NO campaign has behaved as the defenders of privilege always do: telling lies about what is in the people's best interests and issuing one threat after another. A conniving minority is also out there, doing the gentry's dirty work, like the hated factors of old.

There's still time to read The Year of the Stranger before the referendum. Which means there's still a chance to remind ourselves what rule by those-who-believe-they're-born-to-rule tends to mean. It wasn't always thus in the Highlands and Islands. But the Treaty of Union imposed the worst kind of patrician government-by-force on a proud and independent-minded people, and those people were worn down, beaten, cheated by magistrates, bullied by a greedy gentry and terrorised by paranoid ministers.

And that's where we're heading again, unless the Scots display their natural courage, intelligence and sense of social justice, and set themselves free. It only takes an 'X' in a box to rid the land of the fear of the landlord and his factor, and to show the world the way forward again.

Alba gu brath!!

It must be 35 years since I borrowed that book from my local library in Birmingham. Time spent on holiday in Scotland had planted a deep-rooted fascination, bordering on thirst, for all things Scottish. The Hill of the Red Fox, which sits comfortably alongside Stevenson's Kidnapped and Buchan's Thirty-Nine Steps, was one of the stories which allowed me to keep in touch, as it were, with western Scotland when I was back home in the West Midlands. It also inspired my interest in the Gaelic language (there is a little glossary of Gaelic terms in the back, and this fascinated me as a kid - the Gaelic has a dignity, a romance, and a connection with nature that English seldom matches). When the chance arose, I opted to take Gaelic Studies at the University of Glasgow, largely because of the glossaries I had previously found in such books as The Hill of the Red Fox.

Rooting around a charity bookshop in Evesham, a day or two after I'd read The Hill of the Red Fox, I came across an old copy of another novel by Allan Campbell McLean. The Year of the Stranger. I'm reading it now.

Like The Hill of the Red Fox, it's set on the Isle of Skye. But whereas the former novel takes place during the Cold War 1950s and involves espionage, murder and nuclear secrets (all grist to my adolescent mill, back in the late 70s), The Year of the Stranger takes place in the Victorian era. And it paints a perfectly clear picture of the gross injustices of aristocratic rule in the Highlands and Islands.

There's a referendum coming up. The people of Scotland have a choice - do they want independence, or are they anxious to remain in the United Kingdom? I don't have a vote, although I wish I did. The vote will take place the day before my 12th wedding anniversary. I married a woman who is half-Scots. We were married on the Isle of Iona. I can think of no more exciting anniversary present than a resounding YES to Scottish independence.

There are many, many reasons why it's a good idea. Some of them are to be found in The Year of the Stranger. It's a reminder that, after the Treaty of Union between England and Scotland in 1707, the people of Scotland pretty much lost every last one of their rights. They were cleared from their native lands, forced out of their homes to make way for sheep (a lucrative business, but one that destroyed the ecology of the Highlands) or simply to provide an absentee landlord and his wealthy friends with even more empty land to call their own. Servile deference was demanded by the anglicised gentry. That deference was not just demanded - it was imposed by force. While the aristocracy turned Scotland into their own exclusive playground, those to whom the land had belonged were shipped off to America, Canada, Australia, in their thousands. Those who remained behind had no choice but to tug their forelocks and grovel to the latest outsider who called himself their landlord. A terrible punishment awaited those who resisted. The fish in the rivers belonged to the aristocracy; the deer on the hills were theirs. They owned - or believed that they owned - everything.

The spirit of the Highlanders was all but broken. Many went off to fight in Britain's wars (sustaining a disproportionate amount of casualties, compared with the rest of the UK). Those at home found themselves oppressed, not just by the aristocrats, who could buy the law, but also by religious extremists, who forced their neighbours into ever more demoralised forms of mental straitjacket. As always, aristocracy and religious zealotry went hand in hand. The once-proud people learned to live in fear of their outlandish landlords and their crazy preachers. They had become little more than slaves.

It took the 20th century to pull Scotland - and the rest of the UK - out of that moral, political and economic insanity. Votes for all, regardless of income and gender; universal education; welfare; healthcare; collective bargaining. Gradually, civilisation dawned. But all that has now been undermined.

Tom Devine, probably the most respected historian in Scotland, explained why it was time to vote YES to independence. The union was of benefit (he feels) from the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 up till the Thatcherite revolution of 1979. But that's when union with England ceased to be of any real advantage to the Scots. The neoliberal agenda being so ruthlessly pursued by successive British governments is nothing more than a determined attempt to turn back the clock. While the stark picture of gross economic, political and legal inequality as presented by Allan Campbell McLean in The Year of the Stranger strikes us today as quaintly barbaric, be in no doubt that to those who currently hold power in Westminster, that sort of rampant injustice makes perfect sense.

Social and economic progress was turned around in 1979. Margaret Thatcher's simplistic economic policies were an absolute disaster - and yet the receipts from (Scottish) North Sea Oil and Gas propped up the nation's finances, so that things didn't look quite as bad as they really were (and there was always the press to mislead us as to what was really going on). But if the natural wealth of Scotland bailed out Thatcher's failed experiments, it was the Scots who paid the greatest price - their industry practically destroyed. Nuclear weapons? The English wouldn't want them anywhere near their coastal towns. Put them within 25 miles of the most densely populated area in Scotland. Oh, and the poll tax that nobody wanted? That was visited on the Scots a full year before they tried it out in England. Scotland's wealth subsidised Westminster, but rather than show the slightest gratitude, Tory commentators chose to brand the Scots "scroungers" and "subsidy-junkies". That is what colonisation looks like.

If Scotland chooses not to free itself of the shackles of aggressive, patronising, condescending, grasping Westminster rule, it will live to regret it. Scotland is one of the richest countries in the world, and yet hundreds of thousands of its children are falling into poverty as a result of Tory ideology (there is only one - ONE - Tory MP in Scotland). A person from Aberdeenshire, when asked to explain why she is voting YES, said, "When I look out to sea, I see nothing but oil-rigs. When I look inland, I see nothing but food-banks."

And that, folks, is your warning. History is repeating itself. A corrupt and self-serving aristocracy is seeking to take us back to those dark days in which we all had to doff our caps to the idiots who lorded it over us; that, or we starved. They could take our homes, throw us out into the cold, send us overseas, deny us our rights and use lethal force against us. Their obscene wealth was stolen from the millions who actually earned it.

England can, if it chooses, wrap itself up in the Downton Abbey lies about the past and carry on down the road towards government by half-baked toffs and their vicious minions, or the only apparent alternative, which is arse-about-face UKIP-style fascism. But if the Scots want to avoid the iniquities of history being revisited upon them, they need to take the chance that is now on offer.

For one thing is clear. Those who cling to the idea of the union do so for one of two reasons.

The first is that they are the very aristocrats who believe that they own Scotland (and its people, and its natural resources) and who insist on maintaining their privileges, no matter what it takes.

The other is that they have some vague hope that somehow, the Scots and the English and the Welsh and the people of Northern Ireland will someday turn the neoliberal juggernaut around and get us back on the road to democracy and decency. But that ain't gonna happen. The English are too busy blaming everybody else in the world for their mistakes to wake up to the very real trouble they're in. The Scots are already awake. The YES campaign is by far the biggest, broadest, most inclusive and engaged grassroots campaign I've ever seen: a genuine movement of the people. It's not about nationalism. It's about reality. They know that the union is finished, and that Thatcherism killed it. They see democracy slipping ever further and further away, as the gentry comes marching back to lay claim to what it never earned. The NO campaign has behaved as the defenders of privilege always do: telling lies about what is in the people's best interests and issuing one threat after another. A conniving minority is also out there, doing the gentry's dirty work, like the hated factors of old.

There's still time to read The Year of the Stranger before the referendum. Which means there's still a chance to remind ourselves what rule by those-who-believe-they're-born-to-rule tends to mean. It wasn't always thus in the Highlands and Islands. But the Treaty of Union imposed the worst kind of patrician government-by-force on a proud and independent-minded people, and those people were worn down, beaten, cheated by magistrates, bullied by a greedy gentry and terrorised by paranoid ministers.

And that's where we're heading again, unless the Scots display their natural courage, intelligence and sense of social justice, and set themselves free. It only takes an 'X' in a box to rid the land of the fear of the landlord and his factor, and to show the world the way forward again.

Alba gu brath!!

Tuesday, 19 August 2014

More About Arthur and Alyth

"Reekie Linn Waterfall, Angus" by stephen samson - Geograph http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/765407. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Reekie_Linn_Waterfall,_Angus.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Reekie_Linn_Waterfall,_Angus.jpg

*

Not all of the ancient stories about, or inspired by, the historical Arthur use the familiar name of the hero. Two alternative titles or designations which recur in this context are: Bran ("Raven") and Llew (Welsh: "Lion") or Lleu (Welsh: "Light"), the latter also occurring as Lliw or Llyw (Welsh: "Leader"), possibly from the Irish luige, Welsh llw, an "oath".

So let's look at some of the stories which give one or other of these names to their oh-so Arthurian heroes.

Le Chevalier Bran

Among the earliest sources for the "battle of Circenn" in which Arthur died, the Irish Annals of Tigernach name Bran as one of the sons of Aedan, King of the Scots, who fell alongside Artur/Artuir. The Annals of Ulster name Bran instead of Arthur. Adomnan's Life of Columba names Arthur instead of Bran.

In Welsh legend, Bran, the "Blessed Raven", was the "crowned king of the Island of Britain" who fell through the treachery of an Irish king named Matholwch ("Prayer-Sort"). The final battle involved a marvellous cauldron of rebirth, which had been Bran's gift to Matholwch. Along with Bran, who had been fatally wounded by a poisoned spear, there were just seven survivors of this epic battle. There were also seven survivors of Arthur's last battle, according to the contemporary poet and eye-witness, Taliesin.

Meanwhile, the "Horn of Bran the Hard from the North" was one of the Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain ("which were in the North"), the other treasures having belonged to the contemporaries, relatives and near-neighbours of Arthur son of Aedan. A later tradition holds that Arthur had a hound called Bran. The name evolved into the "Brons" of Arthurian romance.

Bearing all that in mind, I was fascinated to come across an old Breton folksong entitled Le Chevalier Bran ou le Prisonnier de Guerre ("The Horseman Bran, or the Prisoner of War"). Published in 1842, this song begins:

A la battaile de Kerlouan

Fut blesse le chevalier Bran!

A Kerlouan, sur l'ocean,

Le petit fils de Bran le Grand!

Prisonnier, bien que victorieux,

Il dont franchir l'ocean bleu.

["At the battle of Kerlouan, the horseman Bran was wounded! At Kerlouan, by the sea, the grandson of Bran the Great! Captured, even though he was victorious, he was taken across the sea."]

There is much that can be said about this intriguing song, with its distinct Arthurian overtones - for example, the song tells of an oak-tree which stands in the field of battle, at the spot where "the Saxons were put to flight when Even suddenly appeared", Even probably being Owain (French "Yvain") who distinguished himself at Arthur's last battle, as we know from Aneirin's epic Y Gododdin poem.

However, for now we need only concentrate on two aspects of the Breton song. The first is that le chevalier Bran was the grandson of Bran le Grand. The grandfather of Arthur son of Aedan was Gabran, the Scottish king who gave his name to the region of Gowrie, in which Arthur's last battle was fought.

What, then, of Kerlouan, where the horseman Bran was wounded and taken away as a "prisoner of war"? At first glance, it appears to refer to the commune of Kerlouan in the Finisterre department of Brittany. But this place-name almost certainly travelled with the British refugees who fled to Armorica, the "Lesser Britain", when their Lothian homelands were conquered by the Northumbrian Angles in circa AD 638. The ker element is cognate with the Welsh caer, meaning a "castle", "stronghold" or "citadel". The louan element refers to St Elouan, otherwise Luan, Llywan, Lua, Lughaidh or Moluag ("My-Luan").

St Elouan or Louan was an obscure saint, said to have been contemporary with St Columba (and, therefore, with Arthur son of Aedan) and to have brought Christianity to the northern, Highland Picts, while Columba spread the Gospel among the southern, "Miathi" Picts (Arthur son of Aedan died, according to the Life of Columba, in "the battle of the Miathi").

The only place where St Elouan or Louan is still venerated as "Luan" is at Alyth, near the site of Arthur's last battle. The Church of St Luan now stands on Alexander Street. The Alyth Arches are all that remain of an earlier church, dedicated to St Luan, which supposedly occupies the site of an even earlier chapel. Alyth, then, has a strong claim to have been the "Stronghold of Luan" or Kerlouan where Arthur/le chevalier Bran was grievously wounded and carried away "across the sea". Any resemblance to the Caerleon which recurs in Arthurian tradition as an early form of Arthur's legendary court (later "Camelot") is probably not coincidental.

Llew Skilful Hand

Llywan is the Welsh form of Luan/Louan. In the ancient Welsh tale of Culhwch and Olwen (which, as I stated in my previous blog post, offers a potted account of Arthur's career, including the violent seizure of a magical cauldron), the treacherous king-turned-boar is finally driven into a river near Llyn Lliwan ("Lake Louan"), which was somewhere near Tawy (the Tay). This lake appears to be remembered on the map of the Alyth area as the Bankhead and Kings of Kinloch, adjacent to Arthurbank beside the River Isla. The marshy ground in the river's floodplain was once known, perhaps, as Loch Luan, a name preserved in the spot, near Meigle, known as Glenluie.

The name of this lake recalls Llew, Lleu or Lliw - as Aneirin sang in his Y Gododdin elegy for the northern warriors who fell in Arthur's last battle:

No one living will relate what befell

Lliw, what came about on Monday at the Lliwan lake.

Apart from the tales of his Irish counterpart, Lugh Long-Hand, the most famous of the British legends concerning Llew or Lleu is that found in the Welsh "Mabinogion", in which a great hero known as Llew Skilful Hand is tricked by his treacherous wife into standing on the edge of a cauldron by a riverbank, where he is speared by his wife's lover (the poisoned spear took a year to make because it could only be worked on during the Mass on Sundays). The name given for the river on the banks of which Llew was speared is "Cynfael".

Now, bear with me here. The bloody boar-hunt in the legend of Culhwch and Olwen which culminates with the destruction of the Boar-King in the river near Loch Tay and the "Lliwan lake" is, in fact, the second of two dangerous boar-hunts which took place "in the North". The first concerned another Boar-King - or, to be more accurate, another king of the Miathi Picts, who modelled their appearance on the boar, hence the Gaelic and Scots names for their territory in Angus: Circenn ("Comb-heads") and Camlann ("Comb-land"). The death of this previous Boar-King of the Miathi Picts can be dated to circa AD 580, some 14 years before the final battle.

His name was Galam, although he went by a couple of epithets. The Annals of Ulster record the death of "Cennaleth, king of the Picts" in 580. The Annals of Tigernach refer to the death of "Cennfhaeladh king of the Picts" in the year 578.

These epithets reveal the location of Galam's power-base in Angus as king of the Miathi Picts. Cennaleth translates as "Chief of Alyth". Cennfhaeladh could indicate a "Shaved-head", as in the boar tonsure sported by the Miathi warriors, or the chief of a "high, rounded hill", such as that which looms over the town of Alyth in the vale of Strathmore. The proper pronunciation of Cennfhaeladh would be "ken-eye-la". This suggests that the name of the River Isla, which flows past Alyth and Arthurbank, derives phonetically from Cennfhaeladh. It also suggests that the Cynfael river, on the bank of which Llew Skilful Hand was treacherously speared by his wife's adulterous lover, was really the Cennfhaeladh or River Isla, on the bank of which Arthur was mortally wounded.

Arthur and his men defeated Galam Cennaleth ("Chief-of-Alyth"), otherwise Cennfhaeladh, in about 580 at the "Battle of Badon" (Gaelic Badain, the "Tufted Ones"), fought a little further up the River Isla at Badandun Hill. Galam's Miathi warriors later joined forces with Arthur's nemesis, Morgan the Wealthy, and the final conflict was fought beneath Barry Hill and the Hill of Alyth, on the banks of the River Isla or "Cynfael".

Seekers of the Grail - which in its earliest form was a magical cauldron - might care to investigate the legend of "Sir James" and his cauldron of enlightenment, a legend centred on the Reekie Linn waterfall, behind the Hill of Alyth (see top of this post). It's quite an eye-opener.

Labels:

Aedan,

Alyth,

Arthur,

Arthurbank,

Badandun Hill,

Badon,

Bran,

Camelot,

Camlan,

Mabinogion,

Meigle,

St Columba,

Taliesin,

Y Gododdin

Monday, 18 August 2014

Naming the Goddess

Coming soon, from Moon Books - Naming the Goddess (Amazon.co.uk details here)

I contributed the chapter on "Christian Wisdom, Pagan Goddess: Reclaiming Sophia and the Saints from the Judeo-Christian Tradition".

Looking forward to reading the book as a whole!

I contributed the chapter on "Christian Wisdom, Pagan Goddess: Reclaiming Sophia and the Saints from the Judeo-Christian Tradition".

Looking forward to reading the book as a whole!

Sunday, 17 August 2014

Alyth, the Scene of Arthur's Last Battle

While I work on Shakespeare's Son - my biography of Sir William Davenant, a man of whom I'm becoming increasingly fond - The Grail continues to make its way through the publishing process, courtesy of Moon Books. So, by way of a sneak preview, in this post I shall offer up some of the evidence for the location of Arthur's last battle.

The Battle of Circenn

You probably think Arthur's last battle was fought at a place called "Camlann". I've been unable to find any reference to that place-name before the Middle Ages. The very earliest mentions of anyone called Arthur in the records indicate that he died in a battle fought in Angus, Scotland.

Adomnan of Iona's Life of Columba (circa 697) tells us that Artur son of Aedan was present when his father was "ordained" king of the Scots by St Columba in AD 574. The saint predicted the fates of Aedan's sons, announcing that Artur would "fall in battle, slain by enemies". Adomnan assured his readers that this prophecy came true when Artur and at least one of his brothers was killed in a "battle of the Miathi".

The Miathi, or Maeatae, were a Pictish tribe: essentially, they held the low-lying lands to the south and east of the Highland massif. Another Latinate term for these people was Verturiones.

The Irish annals, which drew at least some of their information from the records kept by Columba's monks on the Isle of Iona, specify that Artur son of Aedan died in a "battle of Circenn". This refers to the Pictish province which was roughly contiguous with today's Angus and the Mearns. The term Circenn combined the Gaelic cir, meaning a "comb" or "crest", and cenn, "heads". Circenn, then, was the land of the Comb-heads. This tells us that the Miathi Picts modelled their appearance on their totem beast, the boar (rather like their compatriots in the Orkneys, the Orcoi, from orc - a young boar). Indeed, it is possible that the Latinate name for the Verturiones tribe combines verres and turio and indicates the "offshoots" or "offspring" of the "boar", while the very term "Pict" (variant, "Pecti", "Pecht") quite possibly derived from the Latin pecten, a "comb".

Now, let's look at "Camlann" - the traditional name for Arthur's last battle. Its first appearance in the records comes in an entry interpolated into the Welsh Annals, where it refers to a gueith cam lann or "strife of cam lann". By the time this came to be written down, the region in which Artur son of Aedan died was speaking a version of Northumbrian Old English which became the dialect known as Lowland Scots. In that dialect, cam lann would mean "comb land".

In other words, "Camlann" is merely an anglicised version of the Gaelic Circenn, the land of the "Comb-heads" in which the first Arthur on record fell in a cataclysmic battle.

Culhwch and Olwen

One of the oldest of the Welsh (i.e. British) tales to feature Arthur is that of Culhwch ac Olwen. It forms a sort of mythologised, potted account of Arthur's career, culminating in the desperate and bloody hunt for a king who - for his sins - was turned into a boar. This hunt begins with a violent amphibious landing, at a site which can be identified as Cruden Bay, on the Aberdeenshire coast, after which Arthur is met by the "saints of Ireland" who "besought his protection". The dreadful Boar-King is challenged and chased from Esgeir Oerfel, the "Cold Ridge" of the Grampians, the Boar-King making his way across country towards Llwch Tawy (Loch Tay) before he is intercepted by Arthur and his men and driven into a river.

In The King Arthur Conspiracy I identified the treacherous Boar-King as Morgan the Wealthy, a renegade British prince who abducted Arthur's wife, Gwenhwyfar, and escaped into the land of the Miathi Picts (his bolt hole appears to have been the fortified Hill of Tillymorgan in Strathbogie). The site where Morgan finally came to grief is marked by the "Morganstone" on the west bank of the River Ericht, a short distance to the west of the Hill of Alyth in the great vale of Strathmore in Angus.

Arthurian Connections with Alyth

Before we proceed, let us consider some ancient references to Arthur and his family in the context of Alyth and its immediate vicinity.

In addition to having a son named Artur or Artuir, King Aedan of the Scots had a daughter called Muirgein. According to Whitley Stokes, editing and translating the Martyrology of a 9th-century Irish monk called Oengus, Muirgein daughter of Aedan was born "in Bealach Gabrain".

The inability of certain scholars to find a "Bealach Gabrain" in Scotland has led some to argue that Muirgein daughter of Aedan was utterly unconnected with Artur son of Aedan. But place-names evolve. The Gaelic term bealach, meaning a "pass" or "gorge", usually appears as "Balloch" on today's maps. There is a "Balloch" which runs along the feet of Barry Hill and the adjacent Hill of Alyth in Strathmore.

Furthermore, this "Balloch" or bealach was in a region named after the grandfather of Artur and Muirgein. Gabran was the father of Aedan. He ruled the Scots for twenty years until his death in about AD 559 and gave his name to the region of Gowrie (a corruption of Gabran). The "Balloch" near Alyth was in Gabran's land (Gabrain) and lies close to the town of Blairgowrie, which also recalls the name of Arthur's grandfather. The "Balloch" at the foot of the Hill of Alyth was almost certainly the "Bealach Gabrain" or "pass of Gowrie" where Arthur's (half-)sister, Muirgein daughter of Aedan mac Gabrain, was born. To pretend that the Balloch of Gowrie could not have been "Bealach Gabrain" because they are not spelled the same way these days is tantamount to claiming that Londinium and London could not have been the same place.

So Arthur's sister, Muirgein (latterly, Morgan le Fay), was born near Alyth. Writing in about 1527, the Scottish historian Hector Boece also indicated that Arthur's wife was buried at Meigle, which is just a mile or two south of Alyth. Hector Boece's local tradition recalled Gwenhwyfar as Vanora (via Guanora) and claimed that she had been held hostage in the Iron Age hill-fort atop Barry Hill, adjacent to the Hill of Alyth, before she was executed and buried in what is now the kirkyard at Meigle. A carved Pictish standing stone, now on display at the Meigle museum, reputedly depicts the execution or burial of Arthur's wife.

Y Gododdin

One of the best sources of information about Arthur's last battle is the ancient epic, Y Gododdin. This was composed and sung by Aneirin, a British bard of the Old North, and can be dated to circa AD 600 (the date of Arthur's last battle is given in the Irish annals as, variously, AD 594 and 596).

Unfortunately, the relevance of Aneirin's elegiac tribute to the warriors of Lothian (the "Gododdin") has been missed by scholars who want to believe that the poem bemoans the destruction of a British war-band from the Edinburgh area which had the misfortune to be wiped out at a mythical battle fought at Catterick in North Yorkshire. No evidence exists that any such battle was fought. The Angles (forerunners of the English) preferred not to recollect their defeats but were happy to remember, and to boast about, their victories. If the Angles of Northumbria had indeed obliterated a British band of heroes from Lothian at Catterick, we might assume that they would have remembered doing so. And no scholar has yet explained the presence of "Irishman and Picts" at this imaginary battle in Anglian territory.

A verse or two of Y G[ododdin, added at a later date than the original composition, described a battle fought in Scotland (Strathcarron) in AD 642 and the death in that battle of a Scottish king who just happened to be a nephew of Artur son of Aedan. This interpolation does at least suggest that the subject of the original poem was a battle fought in roughly the same area (Scotland) by the family of Artur and his father Aedan. The Y Gododdin poem also mentions various famous warriors who appear in the early accounts of Arthur's career and who were contemporary with Artur son of Aedan.

One surviving version of Y Gododdin even mentions Artur/Artuir by name:

Gochore brein du ar uur

caer ceni bei ef Arthur

rug ciuin uerthi ig disur ...

Confused by the misidentification of the battle sung about by Aneirin in Y Gododdin, and the assumption that Arthur himself could not have been present at that battle, scholars have persistently mistranslated this verse - mostly in an attempt to render the second half of the second line, "He was no Arthur". But Aneirin's verse should properly be translated thus:

Black ravens [warriors] sang in praise of the hero [Welsh, arwr]

of Circenn [transliterated into Welsh as "caer ceni"]. He blamed Arthur;

the dogs cursed in return for our wailing/lamentation ...

Aneirin indicated, in his Y Gododdin elegy, precisely where the final battle took place:

Eil with gwelydeint amallet

y gat veirch ae seirch greulet

bit en anysgoget bit get ...

Which translates as:

Again they came into view around the alled,

the battle-horses and the bloody armour,

still steadfast, still united ...

The "alled" was Aneirin's Welsh-language attempt at the Gaelic Allaid - also Ailt - or the Hill of Alyth.

Breuddwyd Rhonabwy

The extraordinary medieval Welsh tale of The Dream of Rhonabwy actually provides a description of the scene in the hours before Arthur's last battle was fought. The visionary seer, Rhonabwy, finds himself crossing a great plain with a river running through it (Strathmore). He is met by a character call Iddog, "Churn of Britain", who admits that it was he who caused the cataclysmic "battle of Camlan" by betraying Arthur. In company with Iddog, Rhonabwy approaches the "Ford of the Cross" (Rhyd-y-Groes) on the river. A great army is encamped on either side of the road and Arthur is seated on a little flat islet in the river, beside the ford.

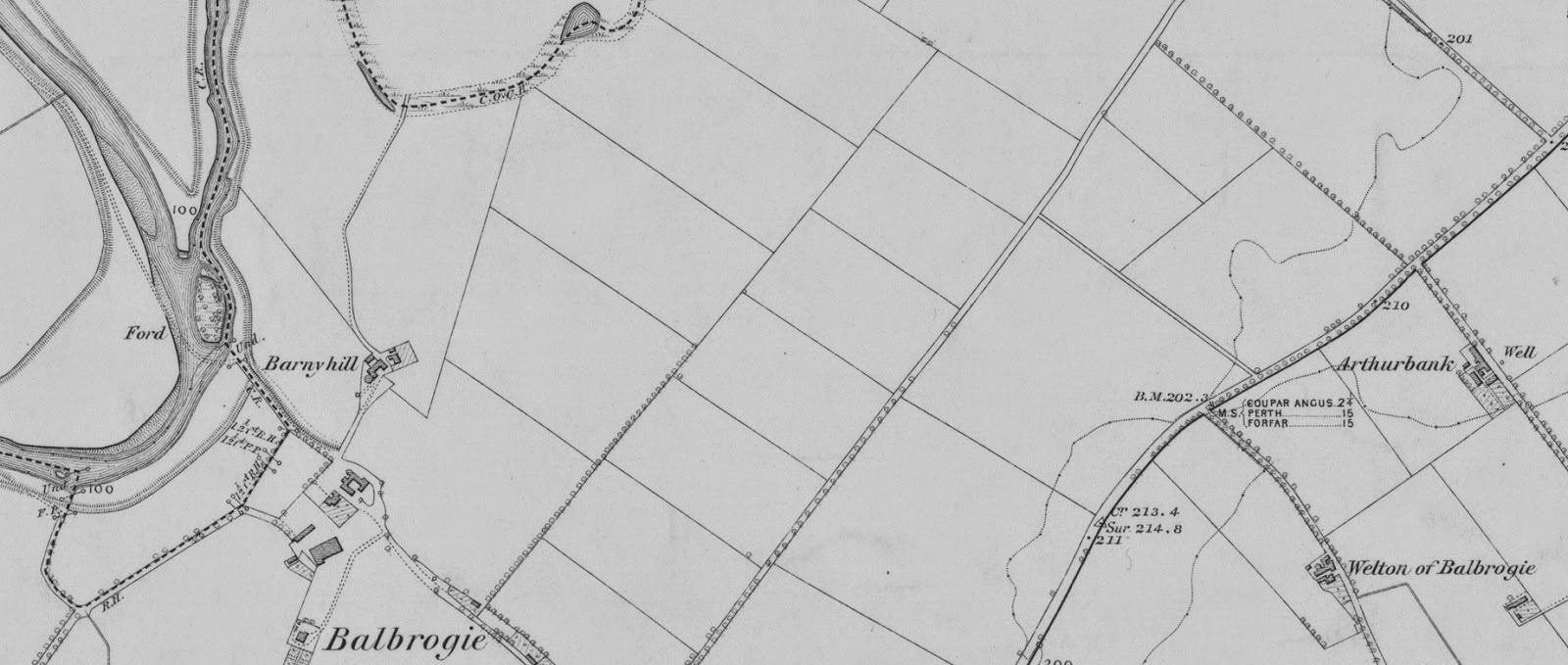

The topography precisely matches the detail from a 19th-century Ordnance Survey map of the area around Alyth seen at the top of this post. On the right-hand side of the detail is the ridge known as Arthurbank, which lies along the River Isla, opposite the junction of the River Ericht with the River Isla (a few miles down the Ericht from the site of the Morganstone). A little flat islet lies in the River Isla, close to the Arthurbank shore, and a ford runs alongside this little islet, exactly as described in the Welsh account of Rhonabwy's dream.

Aneirin also mentioned this ford in his Y Gododdin poem as rhyd benclwyd - the "ford" of the "grey" or "holy mount". There is, indeed, a Greymount marked on the map, a short distance to the north of the ford on the Isla. In his Agriculture of Perthshire, published in 1799, the Rev. Dr Robertson described the discovery of a "large Druidical temple" at Coupar Grange, adjacent to this ford. A standing stone found in this "temple" would no doubt have been rebranded a "cross" by the early Christians, so that the ford across the Isla, beside the little flat islet, would have become known as the Ford of the Cross (Rhyd-y-Groes), as described in The Dream of Rhonabwy, or the "Ford of the Grey/Holy Mount" (rhyd benclwyd) as described by Aneirin.

Until the late 18th century, an Arthurstone stood at the south-eastern edge of the Arthurbank ridge (its presence is still marked on the map). This Arthurstone corresponds to the Morganstone, a few miles away up the River Ericht, and marks the spot where Arthur fell in his battle with the Boar-King of the Miathi Picts in the land of the "crested" Comb-heads, Camlann.

The Head of the Valley of Sorrow

After the battle, Arthur's wife Gwenhwyfar was executed and buried only a mile or so away at Meigle. The legend of Culhwch and Olwen (which, interestingly, features a treacherous individual identified as Grugyn, who also appears in Aneirin's Y Gododdin) tells us that, after the battle at the river with the dangerous Boar-King, Arthur and his heroes once more "set out for the North" to overcome a fearsome witch. She was found inside a cave at Penn Nant Gofid - the "Head of the Valley of Sorrow"- on "the confines of Hell" (which we can interpret as the edge of the territory controlled by those boar-like Miathi Picts). The Welsh gofid ("sorrow/trouble/affiction/grief") appears to have been something of a pun, for another Welsh word for sorrow or grief is alaeth (compare Ailt, Allaid and Alyth, the "Head of the Valley of Alyth" being the very hill on which Arthur's wife is rumoured to have been held prisoner before her execution and burial nearby at Meigle).

In the Welsh tale, this witch is known as Orddu (that is, Gorddu - "Very Black"). A similar legend from the Isle of Mull, whose Arthurian associations have been overlooked for far too long, names the troublesome wife as Corr-dhu ("Black-Crane").

We might also note that the 9th-century Welsh monk known as Nennius described a "wonder" of Scotland in the form of "a valley in Angus, in which shouting is heard every Monday night; Glend Ailbe is its name, and it is not known who makes this noise."

Nennius's Glend Ailbe seems to be a corruption of the Gaelic word for a valley (glen) and the River Isla, or perhaps the Allaid or Hill of Alyth, which dominates the vale of Strathmore. The mysterious shouting in this "Valley of Sorrow" was reputedly heard ever Monday night. And we know from Aneirin's eye-witness account of Arthur's last battle that it came to an end on a Monday.

This is just some of the evidence for Arthur having fallen in the vicinity of Alyth. There is plenty more to come in The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion - including descriptions of the Pictish symbol stones, found close to the site of that battle, which actually depict the Grail in use!

I'll let you know when the book is about to be published.

Friday, 8 August 2014

A Warning to the Curious ...

... or "How History Works" (Part II?).

I was flicking through this book the other day. It's on sale at Tudor World in Stratford, where I'm currently doing the odd Shakespeare Tour and Ghost Tour (and great fun they are, too). What's more, the "Horrible Histories" Gruesome Guide to Stratford-upon-Avon is actually dedicated to the owner, and the phantom residents of, the Tudor World property.

I admire Terry Deary's achievement. His entertaining brand of History-Without-The-Dull-Bits appeals to young and old, no doubt to the despair and disapproval of the more academic types out there. And he does a good job of digging up those obscure facts and stories which tend to be omitted from the standard accounts. In that respect, his Gruesome Guide to Stratford is probably a helluva lot more interesting than the typical guidebook.

He even includes the story of Shakespeare's skull! Yes, the local "legend" which I spent months researching for Who Killed William Shakespeare? So, extra marks there for Mr Deary. Except that he concludes his short account of Shakespeare's missing skull with the information that the skull was safely returned to the Stratford grave.

Almost every account I read of the legend of Shakespeare's skull, as originally recounted by "A Warwickshire Man" (Rev. Charles Jones Langston) in his 1884 publication, How Shakespeare's Skull was Stolen and Found, ends with the information that the missing skull was returned to Stratford.

This recurring "fact" intrigued me while I was researching the story. You see, thanks to the infamous "curse" on Shakespeare's gravestone, the town of Stratford, and Holy Trinity Church, have always been rather diffident about opening up his grave. So how, I wondered, had they managed to get the skull back into the grave, sometime in the late 19th century, without anyone noticing, and with no record surviving of the grave having been reopened?

It puzzled me for quite a while. And then, while I was starting work on the manuscript for Who Killed William Shakespeare? - a breakthrough! The skull is still inside the crypt at Beoley Church. It was NEVER returned to Stratford.

Various photos of the skull were taken at different times in the 20th and 21st centuries - on those rare occasions when the crypt was opened up for an architect's inspection - and those photos prove that the skull stayed exactly where Rev. C.J. Langston found it: in the vault beneath the Sheldon Chapel.

Okay, so ... Why do so many accounts of the story end with "The skull was returned to Stratford", when it quite evidently wasn't?

I've never yet managed to track down the source of that little bit of historical misinformation. I don't know who first decided that the skull had probably been returned to its owner, or who first sneaked that falsehood into the legend. But here's the thing: ever since that bit of false information was added to the story, it has been repeated, over and over again, whenever somebody stumbles across the legend, including, of course, Terry Deary, when he included the tale in his "Gruesome Guide" to Stratford.

I'm not attacking Mr Deary. But I am questioning the way that, once a lie has been introduced into the historical account, it tends to stay there, repeated over and over again, until it becomes a "fact".

I've blogged previously about the will which names Anne/Agnes Whateley, the woman William Shakespeare was first given a licence to marry. Because Samuel Schoenbaum failed to find that particular will, he concluded that Anne Whateley was a clerical error: she never existed. And because Sam Schoenbaum said that, it became "The Truth"! Anne Whateley: the woman who never was. But she did exist.

The case of Anne/Agnes Whateley and the case of Shakespeare's skull are somewhat similar. In both instances, something has been introduced to the approved story of Shakespeare which doesn't suit the peddlers of that orthodox account. Whenever that happens, it seems, the race is on to quash that little problem. With any luck, something will quickly get sneaked into the historical record which neutralises the threat posed by that rogue story. So, Anne Whateley, we are led to believe, "did not exist". The skull "was returned to Stratford". Neither statement is true, and yet both have been repeated ad infinitum.

The skull story is particularly intriguing, in this regard. Given that Stratford has, on the whole, sought (a) to ignore the story of Shakespeare's skull - and the actual existence of that spare skull at Beoley, and (b) to rubbish the story whenever someone mentions it, you do have to wonder. If, as the Shakespeare folks in Stratford insist, the missing skull simply could not have been Shakespeare's, then why is it so important that we all believe it was returned to Shakespeare's grave after Rev. C.J. Langston discovered and identified it? Isn't that a case of having your cake and eating it? If it never was Shakespeare's skull, then there's no need to put out the false rumour that it was returned to Shakespeare's grave.

I think the claim that the skull was returned to Stratford was a deliberate attempt to "close down" the story. An interesting legend, yes, but no need to get excited because the skull came back to Stratford anyway. Certainly, definitely, no need to probe any further. Like the mysterious Anne Whateley, the skull doesn't exist. At least, it doesn't as long as you don't go looking for it.

So, someone set a hare running. To stop anyone from really investigating the strange tale of Shakespeare's missing skull - as told by that pillar of respectability, a Victorian clergyman - somebody made up the part about the skull having been returned to Stratford. Which it never was. But that's what you'll keep reading is what happened.

Unless you read Who Killed William Shakespeare? of course!

Seriously, though. History is not, or should not be, a Wikipedia entry, which anyone can alter as they see fit. The facts matter. Anyone who "plants" a piece of misinformation - such as "the skull was returned to Stratford" - is deliberately misleading people. And the people who seem most easy to mislead are historians, who keep repeating the lie, if only to make sure that you don't go getting any ideas.

I was flicking through this book the other day. It's on sale at Tudor World in Stratford, where I'm currently doing the odd Shakespeare Tour and Ghost Tour (and great fun they are, too). What's more, the "Horrible Histories" Gruesome Guide to Stratford-upon-Avon is actually dedicated to the owner, and the phantom residents of, the Tudor World property.

I admire Terry Deary's achievement. His entertaining brand of History-Without-The-Dull-Bits appeals to young and old, no doubt to the despair and disapproval of the more academic types out there. And he does a good job of digging up those obscure facts and stories which tend to be omitted from the standard accounts. In that respect, his Gruesome Guide to Stratford is probably a helluva lot more interesting than the typical guidebook.

He even includes the story of Shakespeare's skull! Yes, the local "legend" which I spent months researching for Who Killed William Shakespeare? So, extra marks there for Mr Deary. Except that he concludes his short account of Shakespeare's missing skull with the information that the skull was safely returned to the Stratford grave.

Almost every account I read of the legend of Shakespeare's skull, as originally recounted by "A Warwickshire Man" (Rev. Charles Jones Langston) in his 1884 publication, How Shakespeare's Skull was Stolen and Found, ends with the information that the missing skull was returned to Stratford.

This recurring "fact" intrigued me while I was researching the story. You see, thanks to the infamous "curse" on Shakespeare's gravestone, the town of Stratford, and Holy Trinity Church, have always been rather diffident about opening up his grave. So how, I wondered, had they managed to get the skull back into the grave, sometime in the late 19th century, without anyone noticing, and with no record surviving of the grave having been reopened?

It puzzled me for quite a while. And then, while I was starting work on the manuscript for Who Killed William Shakespeare? - a breakthrough! The skull is still inside the crypt at Beoley Church. It was NEVER returned to Stratford.

Various photos of the skull were taken at different times in the 20th and 21st centuries - on those rare occasions when the crypt was opened up for an architect's inspection - and those photos prove that the skull stayed exactly where Rev. C.J. Langston found it: in the vault beneath the Sheldon Chapel.

Okay, so ... Why do so many accounts of the story end with "The skull was returned to Stratford", when it quite evidently wasn't?

I've never yet managed to track down the source of that little bit of historical misinformation. I don't know who first decided that the skull had probably been returned to its owner, or who first sneaked that falsehood into the legend. But here's the thing: ever since that bit of false information was added to the story, it has been repeated, over and over again, whenever somebody stumbles across the legend, including, of course, Terry Deary, when he included the tale in his "Gruesome Guide" to Stratford.

I'm not attacking Mr Deary. But I am questioning the way that, once a lie has been introduced into the historical account, it tends to stay there, repeated over and over again, until it becomes a "fact".

I've blogged previously about the will which names Anne/Agnes Whateley, the woman William Shakespeare was first given a licence to marry. Because Samuel Schoenbaum failed to find that particular will, he concluded that Anne Whateley was a clerical error: she never existed. And because Sam Schoenbaum said that, it became "The Truth"! Anne Whateley: the woman who never was. But she did exist.

The case of Anne/Agnes Whateley and the case of Shakespeare's skull are somewhat similar. In both instances, something has been introduced to the approved story of Shakespeare which doesn't suit the peddlers of that orthodox account. Whenever that happens, it seems, the race is on to quash that little problem. With any luck, something will quickly get sneaked into the historical record which neutralises the threat posed by that rogue story. So, Anne Whateley, we are led to believe, "did not exist". The skull "was returned to Stratford". Neither statement is true, and yet both have been repeated ad infinitum.

The skull story is particularly intriguing, in this regard. Given that Stratford has, on the whole, sought (a) to ignore the story of Shakespeare's skull - and the actual existence of that spare skull at Beoley, and (b) to rubbish the story whenever someone mentions it, you do have to wonder. If, as the Shakespeare folks in Stratford insist, the missing skull simply could not have been Shakespeare's, then why is it so important that we all believe it was returned to Shakespeare's grave after Rev. C.J. Langston discovered and identified it? Isn't that a case of having your cake and eating it? If it never was Shakespeare's skull, then there's no need to put out the false rumour that it was returned to Shakespeare's grave.

I think the claim that the skull was returned to Stratford was a deliberate attempt to "close down" the story. An interesting legend, yes, but no need to get excited because the skull came back to Stratford anyway. Certainly, definitely, no need to probe any further. Like the mysterious Anne Whateley, the skull doesn't exist. At least, it doesn't as long as you don't go looking for it.

So, someone set a hare running. To stop anyone from really investigating the strange tale of Shakespeare's missing skull - as told by that pillar of respectability, a Victorian clergyman - somebody made up the part about the skull having been returned to Stratford. Which it never was. But that's what you'll keep reading is what happened.

Unless you read Who Killed William Shakespeare? of course!

Seriously, though. History is not, or should not be, a Wikipedia entry, which anyone can alter as they see fit. The facts matter. Anyone who "plants" a piece of misinformation - such as "the skull was returned to Stratford" - is deliberately misleading people. And the people who seem most easy to mislead are historians, who keep repeating the lie, if only to make sure that you don't go getting any ideas.

Tuesday, 29 July 2014

Monday, 28 July 2014

Apologia

I've been remiss. Dreadfully so.

The only thing I can say in my defence is that I have been busy writing my biography of Sir William Davenant (Shakespeare's Son) and enjoying myself giving tours in Stratford-upon-Avon - some days, you might see me in doublet and breeches, leading a troupe of tourists or students from one Shakespearean site to another, whilst on Saturday evenings I guide intrepid visitors through the dark delights of Tudor World on Sheep Street, every Ghost Tour threatening to yield at least one supernatural experience. So, yes, I've been busy.

Added to that, my paper on The Faces of Shakespeare is about to be published by Goldsmiths University; Moon Books will soon be publishing Naming the Goddess, to which I contributed a chapter, and my own The Grail; Relic of an Ancient Religion is currently passing through the Moon Books production process. Oh, and I've also been quietly working on a project based on events in 1964-65 for a company set up by a very good friend of mine from my drama school days.

So I hope you'll forgive the radio silence.

Anyhoo - my great buddy and artistic collaborator on The Grail, Lloyd Canning, got a fantastic four-page spread in this month's Cotswold and Vale Magazine, including (as you can see) the cover shot. Lloyd's amazing images really came out well in the magazine, and The Grail got a good mention (as well as my Who Killed William Shakespeare?), which means that we're all very chuffed. A hearty CONGRATS to Lloyd for the well-earned and much-deserved publicity.

I'll try to post another update very soon. I promise.

The only thing I can say in my defence is that I have been busy writing my biography of Sir William Davenant (Shakespeare's Son) and enjoying myself giving tours in Stratford-upon-Avon - some days, you might see me in doublet and breeches, leading a troupe of tourists or students from one Shakespearean site to another, whilst on Saturday evenings I guide intrepid visitors through the dark delights of Tudor World on Sheep Street, every Ghost Tour threatening to yield at least one supernatural experience. So, yes, I've been busy.